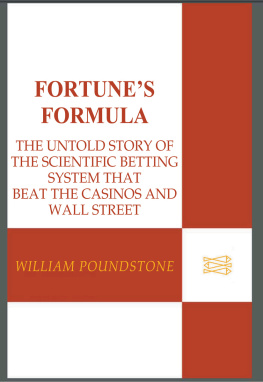

THE UNTOLD STORY OF THE SCIENTIFIC BETTING SYSTEM THAT BEAT THE CASINOS AND WALL STREET

Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

Published in 2005 by Hill and Wang

Poundstone, William.

Fortunes formula: the untold story of the scientific betting system that beat the casinos and Wall Street / by William Poundstone.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Gambling. 2. GamblingHistory. 3. GamblingMathematical models. 4. Shannon, Claude Elwood, 1916 I. Title.

HV 6710. P 68 2005

Prologue: The Wire Service

T HE STORY STARTS with a corrupt telegraph operator. His name was John Payne, and he worked for Western Unions Cincinnati office in the early 1900s. At the urging of one of its largest stockholders, Western Union took a moral stand against the evils of gambling. It adopted a policy of refusing to transmit messages reporting horse race results. Payne quit his job and started his own Payne Telegraph Service of Cincinnati. The new services sole purpose was to report racetrack results to bookies.

Payne stationed an employee at the local racetrack. The instant a horse crossed the finish line, the employee used a hand mirror to flash the winner, in code, to another employee in a nearby tall building. This employee telegraphed the results to pool halls all over Cincinnati, on leased wires.

In our age of omnipresent live sports coverage, the value of Paynes service may not be apparent. Without the telegraphed results, it could take minutes for news of winning horses to reach bookies. All sorts of shifty practices exploited this delay. A customer who learned the winner before the bookmakers did could place bets on a horse that had already won.

Paynes service ensured that the bookies had the advantage. When a customer tried to place a bet on a horse that had already won, the bookie would know it and refuse the bet. When a bettor unknowingly tried to place a bet on a horse that had already lost naturally, the bookie accepted that bet.

It is the American dream to invent a useful new product or service that makes a fortune. Within a few years, the Payne wire service was reporting results for tracks from Saratoga to the Midwest. Local crackdowns on gambling only boosted business. It is my intention to witness the sport of kings without the vice of kings, decreed Chicago mayor Carter Harrison II, who banned all racetrack betting in the city. Track attendance plummeted, and illegal bookmaking flourished.

In 1907 a particularly violent Chicago gangster named Mont Tennes acquired the Illinois franchise for Paynes wire service. Tennes discreetly named his own operation the General News Bureau. The franchise cost Tennes $300 a day. He made that back many times over. There were more than seven hundred bookie joints in Chicago alone, and Tennes demanded that Illinois bookies pay him half their daily receipts.

Those profits were the envy of other Chicago gangsters. In July through September of 1907, six bombs exploded at Tenness home or places of business. Tennes survived every one of the blasts. The reporter who informed Tennes of the sixth bomb asked whether he had any idea who was behind it. Yes, of course I do, Tennes answered, but I am not going to tell anyone about it, am I? That would be poor for business.

Tennes eventually decided he didnt need Payne and squeezed him out of business. Tenness General News Bureau expanded south to New Orleans and west to San Francisco.

This prosperity drew the attention of federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. In 1916 Judge Landis launched a probe into General News Bureau. Clarence Darrow represented Tennes. He advised his client to take the Fifth Amendment. Judge Landis ultimately ruled that a federal judge had no jurisdiction over local antigambling statutes.

In 1927 Tennes decided it was time to retire. He issued 100 shares of stock in General News Bureau and sold them all. Tennes died peacefully in 1941. He bequeathed part of his fortune to Camp Honor, a character-building summer camp for wayward boys.

General News Bureaus largest stockholder, of 48 shares, was Moses (Moe) Annenberg, publisher of the Racing Form . Annenberg was unapologetic about the social benefits of quick and accurate race results. If people wager at a racetrack why should they be deprived of the right to do so away from a track? he asked. How many people can take time off from their jobs to go to a track?

Annenberg hired a crony named James Ragan to run the wire service. By that time, there were scores of competitors. Annenberg and Ragan expanded by buying up the smaller wire services or running them out of business.

One man with the guts to stand up to Annenberg and Ragan was Irving Wexler, a bootlegger and owner of the Greater New York News Service. After Ragan started a price war with Greater New York News, Wexler sent a team of thugs to vandalize Annenbergs New York headquarters.

Annenberg knew that Wexler was tapping into General Newss lines to get race results. It was cheaper than paying his own employees to report from each racetrack. So one day Annenberg delayed the race results on the portion of line that Wexler was tapping. Annenberg had the timely results phoned to a bunch of his own men, who placed big bets on the winning horses with Wexlers subscribers. Wexlers bookies, getting the delayed results, did not know that the horses had already won. By days end, they had suffered crippling losses.

Annenbergs men went to each of Wexlers subscribers and explained what had happened. They refunded the days losses, advising the bookies that it would be wise to switch to General News Bureau.

With such tactics, Annenbergs servicealso known as the Trust or the Wireexpanded coast-to-coast, to Canada, Mexico, and Cuba. In 1934 Annenberg ditched his partners much as Tennes had done. Annenberg established a new, rival wire service called Nationwide News Service. Bookies were told to switch carriers or else.

Hill and Wang

Hill and Wang