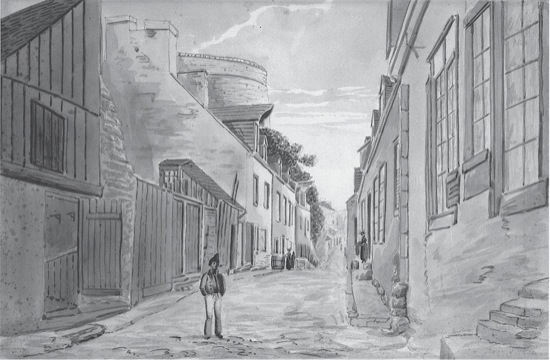

Venue of the Continental Armys first major defeat in the early morning, New Years Day, January 1, 1776. The defenders view looking up the Sault-au-Matelot.

Detail from a painting by James Pattison Cockburn, 1830 (Library and Archives Canada, C-040044).

Copyright

Copyright Gavin K. Watt, 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press and Parks Canada. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Project editor: Shannon Whibbs

Copy-editor: Laurie Miller

Design: Courtney Horner

Epub Design: Carmen Giraudy

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Watt, Gavin K., author

Poisoned by lies and hypocrisy : Americas first attempt

to bring liberty to Canada, 17751776 / Gavin K. Watt.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4597-1764-0

1. United States--History--Revolution, 1775-1783--Campaigns.

2. United States--History--Revolution, 1775-1783--Influence. 3. United

States--History--Revolution, 1775-1783--Participation, Canadian.

4. Canada--History--1775-1783. I. Title.

E230.W28 2014 973.33 C2013-907405-8

C2013-907406-6

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and Livres Canada Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

The publisher is not responsible for websites or their content unless they are owned by the publisher.

Visit us at: Dundurn.com

Pinterest.com/dundurnpress

@dundurnpress

Facebook.com/dundurnpress

Acknowledgements

I am again indebted to the selfless assistance of my re-enacting friend Todd Braisted, a Fellow of the renowned Company of Military Historians and the foremost authority concerning the American loyalists. Todd shared several archival findings that added considerable depth to this tale of the early war.

The ever-generous Dr. John A. Houlding, of Fit for Service fame, contributed many details of Regular officers careers, some of whom later served in the Provincials.

I am deeply grateful to the superb Dictionary of Canadian Biography for many in-depth studies of contemporary personalities.

My friend Mario Lemoine kindly supplied me with photographs of the Quebec Gazette , which provided a great many details of the invasion years.

The Royal Highland Emigrants played a critical role in the defence of Canada and their historian, Kim Stacy, was of great help in describing their efforts.

My portrayal of the rebels regime in Montreal was greatly enhanced by Elinor Kyte Seniors study, Montreal in the Loyalist Decade 17751785. Consulting her work reminded me how limited I am in my study of Canadian history without a thorough knowledge of the French language.

Paul L. Stevenss doctoral thesis, His Majestys Savage Allies, was a key resource to understanding the Natives reactions to the rebel invasion and the actions taken in the far west.

I am beholden to Christopher Armstrong, who applied his wonderful skills to design the books cover and to enhance many images and maps, and to John W. Moore for his photograph of moi, the ancient faux-warrior.

Gavin Watt

King City, Ontario

2013

Introduction

M y use of the term Canadian to refer to the anglophone citizens of Quebec is anachronistic, as that descriptive did not come into common use until the time of the War of 1812. Nonetheless, it is the clearest method of delineating Quebeckers who had come from Britain, Europe, and the lower colonies and were resident in the province before the American rebellion.

When I employ the word Canadien, I am referring exclusively to franco-Canadians. When I use the term Canadian, I am referring either to anglo-Canadians or to both.

Also, I confess to mixing French and English spellings, in particular place names such as Quebec City, Montreal and Fort St. Johns, which appear solely in English, and others, such as Trois-Rivires, which appear only in French. I often employ hyphens in the Quebecois manner, but not always thus, le-aux-Noix. Am I at times inconsistent? Yes, I am afraid so, but that is one of the delights of living in a bilingual country.

The Intolerable Quebec Act

Joy, and Gratitude, and Fidelity to the King

Carleton Returns to Quebec

After a four-year absence in Britain, Guy Carleton resumed the governorship of Quebec Province on September 18, 1774. During the time away he had helped to pilot the Quebec Act through Parliament. Now, on his second day back in office, he opened a dispatch from his military superior, Lieutenant-General Thomas Gage, the commander-in-chief (C-in-C) for North America, and read orders to dispatch the 10th and 52nd Regiments to Boston to assist in clamping a lid on the intense discontent that had begun to boil after the June 1 closure of the port. Disturbingly, those two regiments constituted one half of Carletons infantry for the defence of the settled portions of Quebec.

While in England he would have heard a great deal about American reactions to Parliaments attempts to raise revenue, yet he could not possibly have realized the depth of unrest in the old British colonies. Nor could he have anticipated Quebeckers reactions when Gage complicated the situation by enquiring whether a Body of Canadians and Indians might be collected, and confided in, for the Service in this Country.

Both Gage and Carleton had strong personal memories of the competence and valour of the Canadien militia during the French regime. The practice of compulsory service established in Quebec had effectively militarized the general male population. Although Canadien numbers were small compared to the manpower of the British colonies, the habitants had become accustomed and hardened to mandatory martial duties and were able to play merry hell with British colonial expansion. In the late 1750s, however, France was threatened around the world by British encroachment into its more valuable colonial zones, such as the Caribbean, and found it necessary to withdraw active support for Quebec. Consequently, in 1760 the colony was literally swamped by British armies and fleets, and ultimately succumbed.

![Watt - The 90-day screenplay : [from concept to polish]](/uploads/posts/book/103527/thumbs/watt-the-90-day-screenplay-from-concept-to.jpg)