This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Osprey Publishing,

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA

E-mail:

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

2015 Osprey Publishing Ltd

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4728-0754-0

E-book ISBN: 978-1-4728-0756-4

Editorial by Ilios Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK (www.iliospublishing.com)

www.ospreypublishing.com

DEDICATION

For our parents and ancestors Oscar E. Gilbert Senior (Colonel Thomas Brandon), Elsie Kendrick Gilbert (Privates Abel Kendrick and Lewis Turner), James D. Rittmann Senior (Colonel George Dashiell, Somerset County Militia, Maryland; Private William Mardis, 11th Virginia Regiment and Virginia Militia; and Private Robert Marshall, 6th Regiment Maryland Line), and Sarah Wintter Rittmann Ponder (Lieutenant Richard Hodges Junior, Upper 96th Regiment, South Carolina Militia).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the cooperation of Marti Mangiello and the staff of Inn of the Patriots, Grover, NC; Michael Scoggins, Southern Revolutionary War Institute, York, SC; Bobby Gilmer Moss, Professor Emeritus, Limestone College, Gaffney, SC; Charles Baxley, Southern Campaign website; re-enactors Bob McCann, Robert Ryals, Ricky Roberts and others; Joe Epley; Kara Newcomer of the US Marine Corps History Division; and Elizabeth Gilbert-Hillier for research in the British National Archives. Archival resources were provided by the Fondren Library of Rice University, Houston, TX; the Houston Texas Public Library, particularly the Clayton Library Center for Genealogical Research; and the National Archives I, the Library of Congress, and the Daughters of the American Revolution Library in Washington, DC. Imagery was provided by Military and Historical Image Bank; the National Archives II, College Park, MD (NARA); the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library, Providence, RI; the American Revolutionary War Living History Association, Grover, NC; the US Marine Corps History Division MCB Quantico, VA (USMCHD); and the British National Archives.

ARTISTS NOTE

Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the colour plates in this book were prepared are available for private sale. The Publishers retain all reproduction copyright whatsoever. All enquiries should be addressed to:

www.steve-noon.co.uk

The Publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon this matter.

Osprey Publishing is supporting the Woodland Trust, the UK's leading woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees.

PATRIOT MILITIAMAN IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION 177582

INTRODUCTION

When war begins, then Hell opens. English proverb

Americans have a romanticized view of the militias role in the War for Independence. American generals of the era knew that disciplined Regulars would be necessary to win independence, and on the whole the militia played a relatively minor role. The militias inability to stand in the face of a resolute British attack often brought disaster upon their companions of the Continental Line. In 1776 George Washington said if I was called upon to declare upon Oath, whether the Militia have been most serviceable or hurtful upon the whole, I should subscribe to the latter.

The purpose of the Whig militia was the traditional role of local defense against raids and local offensives by the British and their Indian allies. The Patriots those rebelling against the Crown more commonly called themselves Whigs; see glossary. The period-appropriate term Indian is used here, as opposed to Native American. Another common role of militia was to keep their Tory neighbors under control. Nowhere was this function more important than in the Delmarva Peninsula east of Chesapeake Bay shared by Delaware, Maryland and Virginia. The breadbasket of the Revolution supplied food moved by coastal vessels for Patriot armies to the north and south. The Royal Navy often controlled the Bay, intercepting water traffic and raiding at will. Militia often proved incapable of opposing even small landing parties.

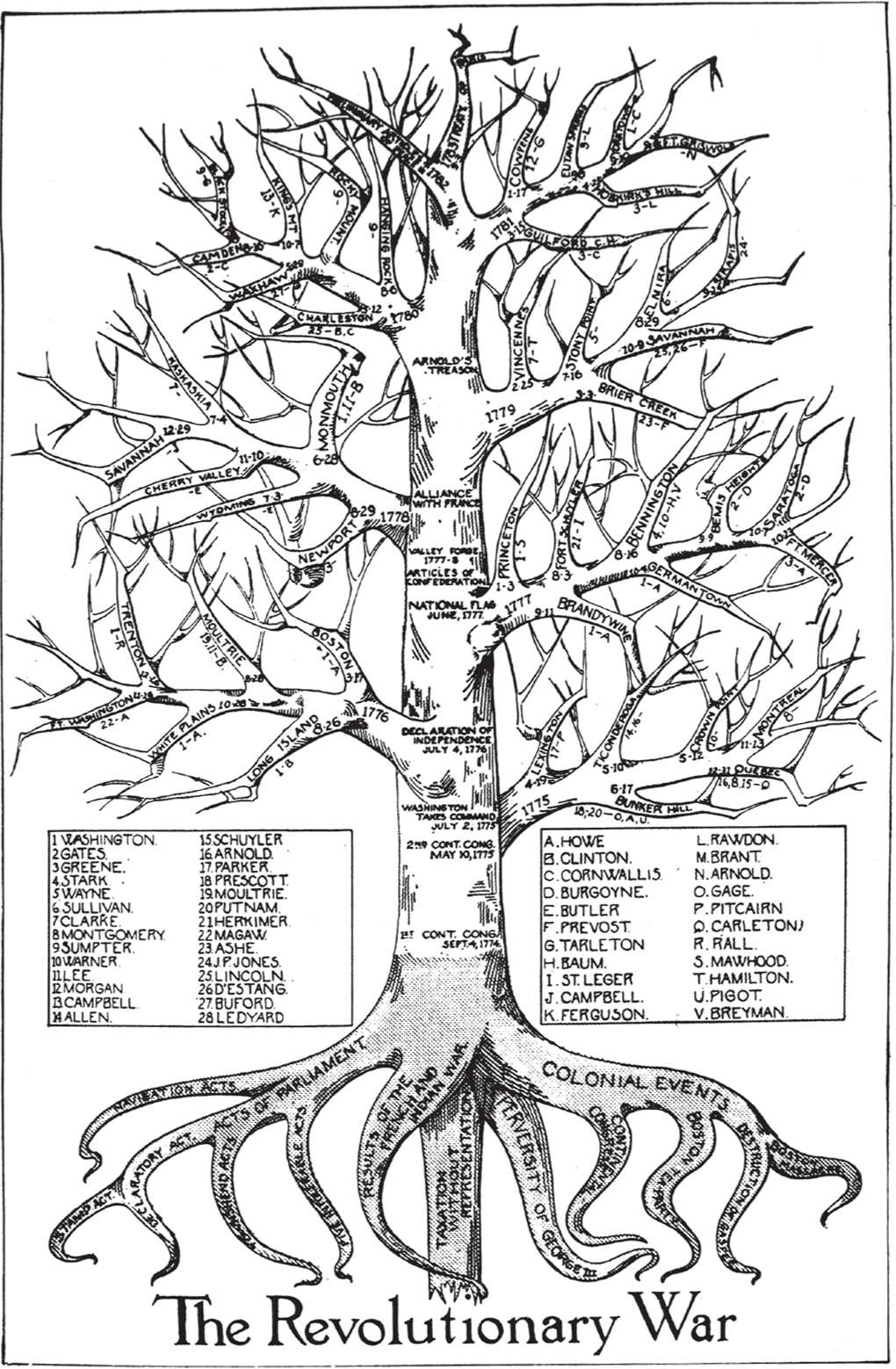

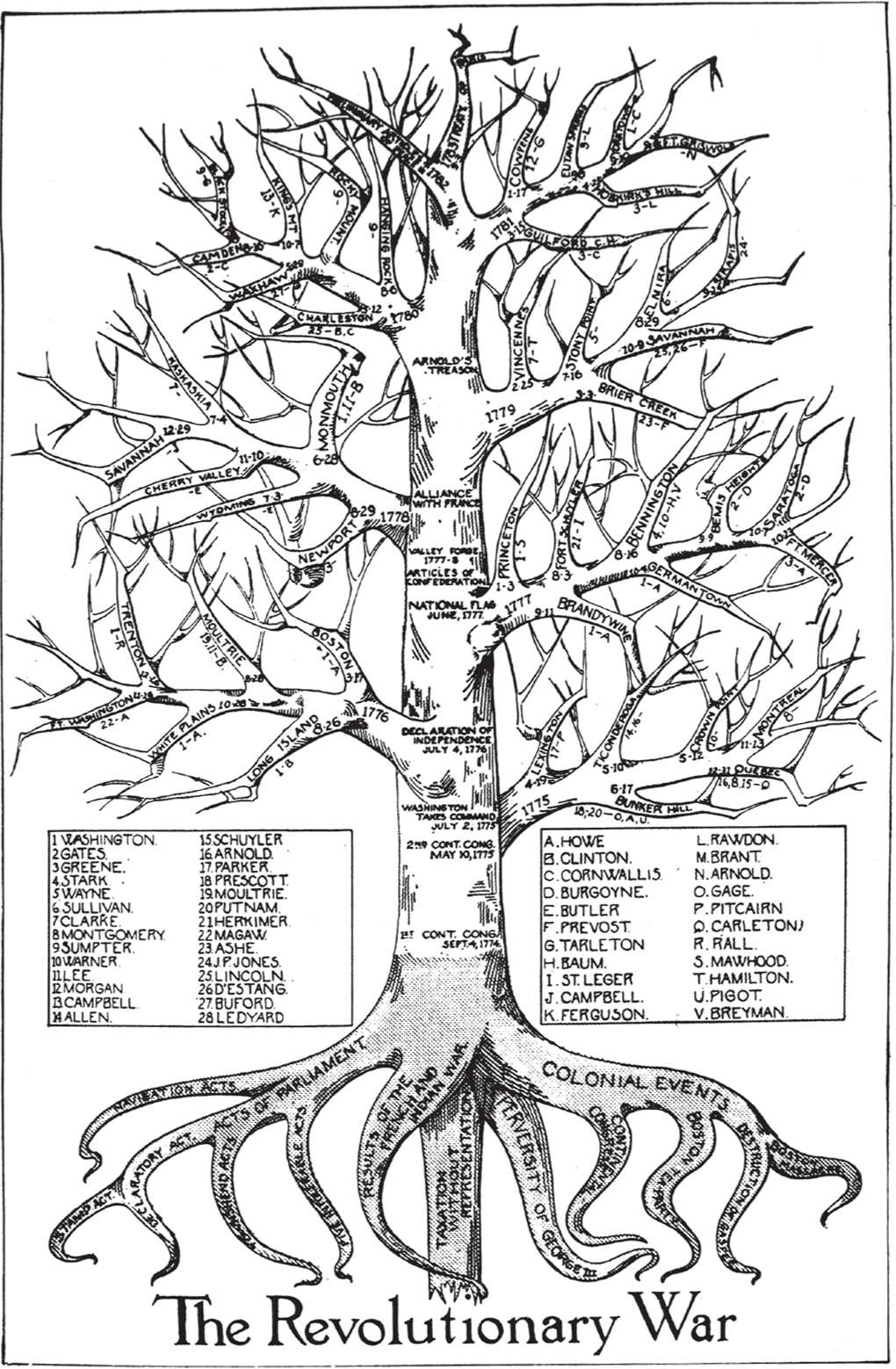

The Southern Campaign was once widely acknowledged as decisive. The tree of liberty had its roots in colonial grievances, and, as its highest branches, the Southern Campaign battles. More actions were fought in South Carolina than in any other colony. (NARA)

Paintings like The First Blow for Liberty by A.H. Ritchie color modern impressions of the militia. New England minutemen probably wore the clothing of townsmen and affluent farmers. (NARA)

Captain Henry Hooper of the Dorchester County (Maryland) Militia mustered his company to oppose a landing party, and found a British brig and two sloops anchored off Vienna. His company had only 12 firearms among them. Hooper was presented with an ultimatum; he could let the British purchase supplies, or he could resist and the British would seize the supplies and burn the town. He chose the former. Called to account for his actions, he was cleared of charges.

The British retreat from Concord and Lexington fostered a persistent myth that the British fought from formations in the open. The retreat was of necessity road bound, but the British Army was experienced in frontier warfare. (NARA)

In sharp contrast the militia played a major role in thwarting the British Southern Strategy in Georgia and the Carolinas. From 1779 onward the fate of the new nation hinged upon the success or failure of untrained militiamen.

At the beginning of the Revolution the hotbed of resistance was New England and Virginia. In the South, the desire for independence was led by the affluent traders and plantation owners of the coastal regions. The people of the back-country had more pressing issues: surviving harsh winters and Indian raids. Yet the South was strategically important. Wealthy Charleston was the fourth-largest port in America, and a major hub of trade in rice and indigo. New England was fighting the revolution, the middle colonies were feeding the rebel troops, and the South was funding the war.

After General Burgoynes disastrous defeat at Saratoga in late 1777 (see Campaign 67: Saratoga 1777, Brendan Morrissey, Osprey Publishing: Oxford, 2000) encouraged French intervention, Loyalist exiles in London convinced the government that Crown sentiment was strong in the South. Georgia and South Carolina could be quickly subdued, and the other colonies rolled up from the south. With control of the sea, the British moved their army south, and in 1778 captured several ports to serve as bases for subjugation of the South.