THE SWAMP FOX

Francis Marions Campaign in the Carolinas 1780

DAVID R. HIGGINS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

For at least as long as large, conventional military forces have taken the field, irregular units have operated on the periphery, accomplishing those missions better suited to a less-regimented force. For conventional forces, the fact of being a state-supported or legitimate army, taking the field to conduct a stand-up fight against a similarly raised, armed, and organized adversary, merited a certain moral superiority. Such warfare was seen as having a semblance of rules, and limited the scope in which non-combatants were generally outside the purview of decisive battles of annihilation. Governmental forces further endeavored to use every instrument of national power to promote order and sustain their position. For them, maintaining security in an unstable environment required vast resources and incurred the handicap of frequently deviating from combat operations to achieve success.

When fighting from a place of weakness against such an adversary whether it was numerically, technologically, or financially options that were not as established or desirable were often all that was available to an insurgent or similar resistance movement bent on changing the political status quo. By definition, participants in such guerrilla wars tended to operate in distributed, less structured groups, which were often deemed less accepted or ethical because of the nature of their imposed methods of fighting. While the officers and men of such units were similarly held in poorer esteem than their conventional counterparts, they were often more reliable, mobile, and motivated when supplied with accurate intelligence, and certain of their cause. Strong leadership and individual initiative maximized movement, rapid combat tempos in the attack and defense, and a units ability to blend into the surrounding population or terrain. Experienced irregulars or partisans relied on being able to adapt rapidly to a variety of environments, climates, and situations to best ensure sustainment and ultimately survival. Limited in the amount of damage they could inflict on soft or inadequately defended enemy assets, including logistics or static, isolated outposts offered the choicest targets. They were also relatively free to use every tool at their disposal to sow as much chaos and disorder as possible to achieve their goals. Although such tactics tended to amount to harassment if taken in isolation, the cumulative effect of such actions over enough time and space could wear significantly on a more established opponents ability to operate.

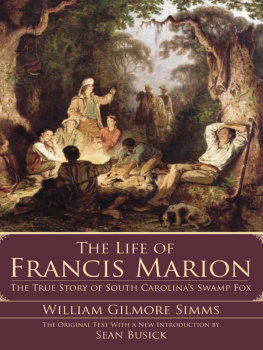

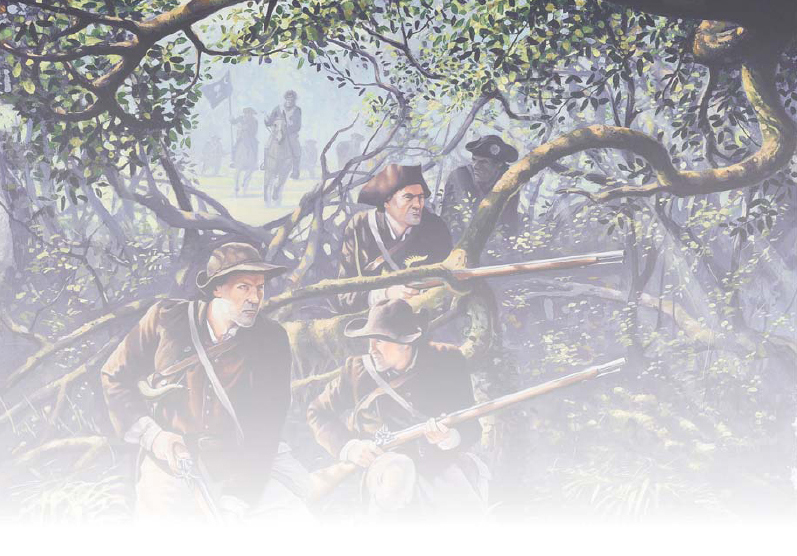

With South Carolina largely consisting of undeveloped wilderness, waterways often facilitated movement better than the areas poorly maintained roads and trails. Boats, including flat-bottom varieties, such as those depicted here with Marion (mounted, second from left) on the Pee Dee River, proved to be valuable military assets. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Providence, RI, USA)

As both sides attempted to outmaneuver or outlast the other and achieve ascendancy, winning over the population and gaining its acceptance as the legitimate governmental authority was paramount. To this end, government forces operated with the confidence that they were more or less invulnerable and actively sought a decisive battle with the guerrillas. When engaged in such a struggle, the design of the counterinsurgency campaign needed to reflect the populations cultural realities and social norms and conventions of war and peacemaking to communicate intent effectively. Should both sides effectively play to their strengths and fail to defeat the other, a stalemate could result. Although most combat, however violent and indiscriminate, relied on a modicum of accepted boundaries, such unresolved, festering conflicts frequently degenerated into a civil war, in which the social movements of neighbors and families frequently devolved into barbarity and terrorism. Even though such actions failed to serve a rational political objective or replace the parent social movements ideology, participants often maintained an association with the larger effort.

Intended to be placed atop an 11ft pedestal at a new veterans memorial park at Venters Landing (aka Witherspoons Ferry), Alex Palkovichs 10ft 6in-wide and 7ft-tall bronze sculpture depicts Francis Marion riding Ball, named by Marion for its former Loyalist owner. (Courtesy of Alex Palkovich)

As the colonial possessions of Britain, France, and Spain pushed inland in the Americas during the 17th and 18th centuries, the large spaces and small populations meant irregular militias or similar bands were organized from the surrounding population to provide localized law and order or, in more established capacities, as supplementary forces for a conflicts duration. Typically these were directed against raids from native tribes that were being steadily pushed from their ancestral hunting grounds, foreign encroachment, or as protection against marauders. While in the relatively open European terrain British and French forces tended to rely on large, conventional armies and supplementary mercenaries, such forces were impractical in North America, which was a thinly populated country that produced little food, except along navigable rivers or where established land transport had been developed. In adapting to less formal tactics, much was based on light-infantry Jger (huntsmen) formations that Prussias King Frederick II instituted in the mid-1700s to perform duties such as infiltration, harassment, and reconnaissance.

With British and French forces possessing a legacy of large, permanent militaries, both tended to view American colonial military efforts with disdain, with one contemporary European observer stating that they were a contemptible body of vagrants, deserters, and thieves. Many settlers had a relatively high standard of living and, and although most were willing to defend their property and homes, they generally lacked the incentive to fight beyond their respective militias operational zones, or adhere to regimented military practices. Their frontier backgrounds, however, promoted firearms use, hunting, and horsemanship, which, in combination with experienced fighting natives, a mentality of self-sufficiency, and living in a largely wilderness environment, made colonial militia particularly adept at irregular warfare. As such, at the revolutions beginning in 1775, a British general prophetically wrote, Our army will be destroyed by damn driblets America is an ugly job a damned affair indeed.

ORIGINS

As with any insurgency, the incubation stage of what became the American Revolution had festered for several years before the outbreak of open hostilities. Since the 1600s, maritime European nations had actively sought new colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia to stimulate their economies and increase their respective wealth. As these overseas possessions prospered via cheap natural resources such as gold, cotton, timber, tobacco, sugar cane, and furs, friction over determining their ownership, in addition to that of territory and trade, was common. As these resources were generally shipped to their respective home countries, converted into finished goods, and then resold to the colonists at inflated prices, Britain largely ignored its North American possessions. Amid the prevailing mercantilist, zero-sum mentality, in which European economic theory stressed that the more money one possessed, the less there was available for other potentially rival nations, exploitation was the result.