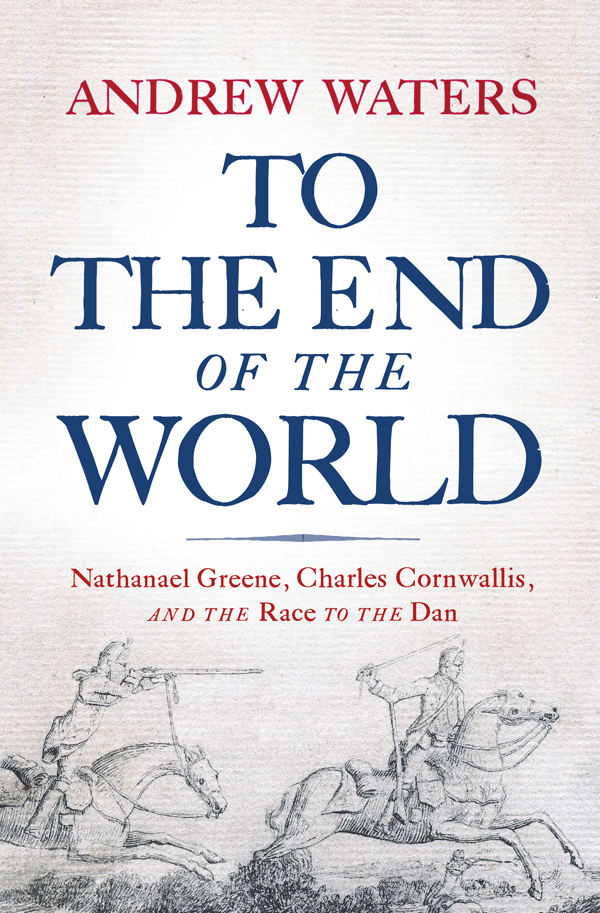

Title page: A ca. 1779 sketch of the British 17th Light Dragoons charging.

(Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

INTRODUCTION

RIVERS ARE MY BUSINESS. As a land conservationist, my job often focuses on river corridors and watersheds. It makes sense if you think about it. Most of us get our water from the nearest river, and land conservation along river corridors helps keep water clean by providing natural filtration. So many conservation efforts focus on strategic corridors along these rivers to protect that most precious of natural resources. In fact, many land conservancies denote their service region as the watershed of a specific riparian area.

My land conservation career has centered on three of these watersheds. My first conservation job was at the Catawba Land Conservancy, focused on North Carolinas lower Catawba River Basin. From there I went to the Land Trust for Central North Carolina (now called the Three Rivers Land Trust), where our work focused on the Yadkin/Pee Dee River, centered around the Piedmont town of Salisbury, North Carolina. And most recently, I worked at the Spartanburg Area Conservancy in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where our focus was on South Carolinas upper Broad River Basin, including the Pacolet River.

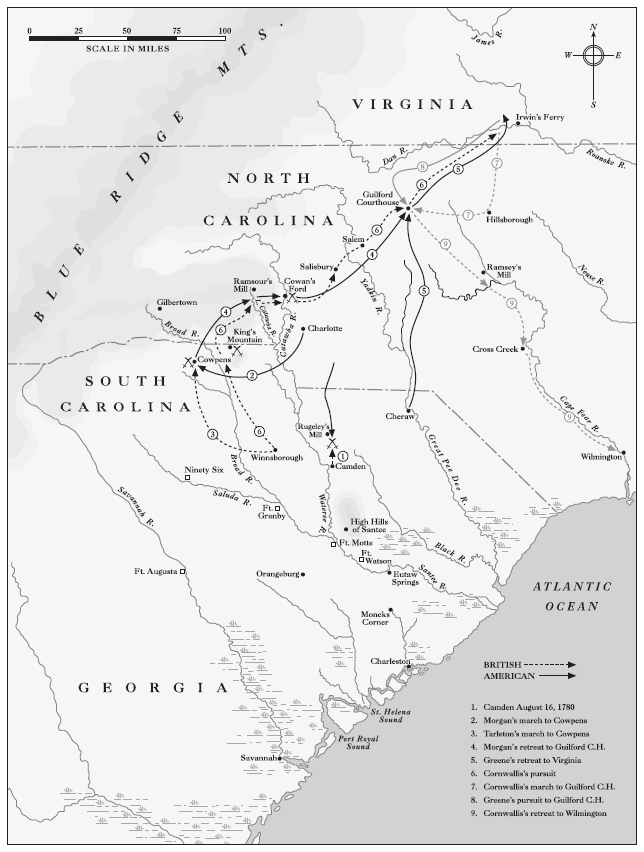

Rivers were also Nathanael Greenes business, though in a very different way. As quartermaster general of the Continental army, the armys chief corporate officer in charge of transport, supply, camps, and troop movement, Greene looked to rivers for transportation. And as one of the armysmost talented generals, he understood implicitly the strategic significance rivers could play in any theater of operations. When Greene took command of the Continental armys Southern Department, which I refer to as the Southern Army in this book, Greene hoped the Souths vast network of rivers could alleviate some of the substantial supply issues facing these southern troops. Even before arriving in the South in late 1780, he had discussed strategies and designs for river transport with George Washington and others, including Thomas Jefferson. And as you shall read, he devoted considerable attention to studying three strategic river corridors traversing Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina: the Catawba River, the Yadkin/Pee Dee River, and the Dan River, a major tributary of the Roanoke River. And when Greene sent Daniel Morgan to the west side of the Catawba in December 1781, Morgan crossed into the Broad River Basin, setting up operations at a well-known location on the Pacolet River.

These four riversthe Broad, the Catawba, the Yadkin, and the Danwould go on to play a starring role in the Race to the Dan, Greenes strategic retreat across the Carolinas into Virginia, just as three of them have starred in my own career. And though he would never use them as transport, as he originally intended, the study he devoted to them would reap strategic dividends in his conflict with Cornwallis.

BUT IT WASNT THIS RIPARIAN CONNECTION that first attracted me to the story of the Race to the Dan. Like so much of my fascination with the American Revolutions southern campaigns, it was John Buchanans book The Road to Guilford Courthouse that first ignited my fascination. As a native Carolinian, born in North Carolina and now residing in South Carolina, reading Buchanan to me was like revelation; through him I became aware of the incredible American Revolution history swirling all around me.

Before Buchanan there were hints. I remember Joe Morris, my colleague at the Land Trust for Central North Carolina, telling me the story of Nathanael Greene arriving alone at Steele Tavern in Salisbury, recounted here in . In it, Greene arrives at the Salisbury tavern alone deep in the night, after a solo ride across the war-torn countryside of North Carolinas Rowan County. As you shall read, it is a remarkable instance of Greene in isolation, traveling alone through an active war zone, hardly believable now and even less so then, as Joe is known for never allowing the facts to get in the way of a good story.

I lived in Salisbury for seven years, and outside of this office chatter, I rarely heard anything about the Race to the Dan, or heard it discussed in a cohesive context, though the city plays a central role in its story. As I note in a closing chapter of this book, wars arent taught in American schools anymore, and if this shift to a study of culture and sociological movements from one of warfare is understandable in an increasingly diverse and politically sensitive world, its unfortunate that campaigns like the Race to the Dan have been forgotten. In a place like Salisbury, you can live among its ghosts and still not know its there.

Too bad. For the Race to the Dan is a remarkable tale, fit for cinema or an epic novel, and not only for its accounts of four narrow escapes across its four rivers. True, conflict is always a component of great narrative, and the Race to the Dan has plenty of it, but character and context also contribute. The American Revolution is not only the story of our nations birth, it was also a revolutionary period of thought. Ideas about politics, philosophy, technology, law, and society were shifting rapidly, and warfare was no different. Thanks to writers like the Prussian king Frederick the Great and Maurice de Saxe, the illegitimate son of a Polish king who went on to fame as a European soldier of fortune, military theory was shifting from battlefield mechanics to the more nuanced craft of petite guerre, or partisan warintelligence and sabotage, ambush, terror, and reconnaissance conducted with small detachments. And petite guerres tenets not only emphasized light, or mobile troops, over the conventional soldiers of the line that had dominated European battlefield tactics for centuries but also a new brand of military officer capable of unusual self-reliance.

The Continental army lacked manpower and resources, but it was blessed with talented officers like Nathanael Greene and the Virginia backwoodsman Daniel Morgan, who embodied petite guerres doctrines. From early in the American Revolution, the Continental army had turned to these partisan tactics not out of intellectual curiosity but sheer necessity. Outmanned and outgunned from the beginning, George Washington relied on light troops and irregular militia led by talented junior officers not because he was a devotee of Saxe but because he had no other options. Washington was learning partisan tactics on the job, and under him was one of Americas most talented military students, his protg Nathanael Greene.