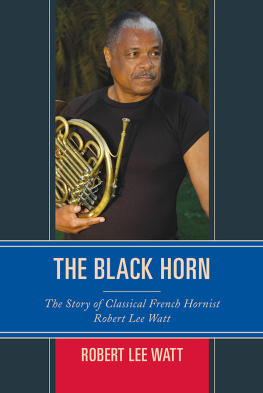

The Black Horn

African American Cultural Theory and Heritage

Series Editor: William C. Banfield

The Jazz Trope: A Theory of African American Literary and Vernacular Culture , by Alfonso W. Hawkins Jr., 2008.

In the Heart of the Beat: The Poetry of Rap , by Alexs D. Pate, 2009.

George Russell: The Story of an American Composer , by Duncan Heining, 2010.

Cultural Codes: Makings of a Black Music Philosophy , by William C. Banfield, 2010.

Willie Dixon: Preacher of the Blues , by Mitsutoshi Inaba, 2011.

Representing Black Music Culture: Then, Now, and When Again? , by William C. Banfield, 2011.

The Black Church and Hip-Hop Culture: Toward Bridging the Generational Divide , edited by Emmett G. Price III, 2012.

The Black Horn: The Story of Classical French Hornist Robert Lee Watt , by Robert Lee Watt, 2014.

The Black Horn

The Story of Classical French Hornist Robert Lee Watt

Robert Lee Watt

Rowman & Littlefield

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom

Copyright 2014 by Robert Lee Watt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Watt, Robert Lee.

The black horn : the story of classical French hornist Robert Lee Watt / by Robert Lee Watt.

pages cm. (African American cultural theory and heritage)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-3938-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-3939-5 (ebook)

1. Watt, Robert Lee. 2. Horn playersUnited StatesBiography. 3. African American musiciansBiography. I. Title.

ML419.W38A3 2014

788.9'4092dc23

[B]

2014018746

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

I dedicate this book to my family and my dear friend, the late Jerome Ashby.

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge my longtime friend Elston Carr for long ago recognizing my need to write a book, after hearing me complain so much about my orchestral life. In a phone message he said, You need to write, Negro!

I am also extremely grateful to my friend Marcus Eley for yelling at me to start writing my book: There are your millions, in your book! He also assisted me in the early stages of my manuscript preparation and in countless other ways.

I also give thanks to Euterpe (Greek Muse of Music), for helping me, via music, to call forth the emotional memories to effectively write about my past. I am also extremely grateful to that goddess of voice, Mezzo Soprano, Jessye Norman, whose recording of Richard Strauss Vier Letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs) transported me there. I would like to thank writer, Mery Grey for introducing me to my first editor, Iris Schirmer (formerly with Random House), who helped me cut my book down from its formerly immense size.

I would like to thank my dear friends Todd Cochran and his wife, Hasmik, for their continued support and encouragement while writing my book.

I also wish to acknowledge many others who helped me in countless way during this process: Tina Huynh; Dr. Courtney Jones; Daisy Newman of the Young Musicians Choral Orchestra of Oakland, California; Raynor Carroll of the Los Angeles Philharmonic; and especially my familymy cousin Marjorie Nickelberry, my little brother Tony M. Watt, my big brother Ronald B. Watt, my big sister Judith Watt-Carson, and my little sister Gail D. Wattfor their helpful memories and insights.

Chapter One

Prelude

I was born into this world at a time when my father, after shining shoes all day at the Berkeley-Carteret Oceanfront Hotel, was not allowed to swim in the public swimming pools at the beach in Asbury Park, New Jersey. He angrily related the racist reality to us in those days:

When I wanted to swim after work on those hot summer days I was not allowed to go into the swimming pools down at the beach, even though the sign on the building said in great big letters, PUBLIC BATHING.

Those crackers laughed as they told me, Hey, boy, why dont you go on over to the colored beach and swimbut you might drown trying cause theres lots of sewer pipes in that water.

When I wanted to go see a movie, black people had to sit in the balcony and the ushers didnt see you to your seat; they just directed you to the balcony and you were on your own.

I went to a segregated grade schoolBangs Avenue School. There was a black principal and a white principal and all the classes were totally segregated. The entire school building was divided with blacks on one side and whites on the other. We even had separate playgrounds.

Even if you wanted to take a road trip on the highway, you had to know in advance where you could stay overnight, where you could stop for gas and get served, where you could stop to eat or just get a lousy cup of coffee.

There was actually a published manual, The Negro Motorist Green Book , that listed the places you could stay, get a haircut, get gas, or even which Chinese restaurants served colored. The book was an international travel guide for every state in America, Mexico, Bermuda, and Canada. There just wasnt much black people could do in those days without having to first think if they would be admitted or turned away. You were just supposed to know your place as a black person. It was a horrible time to be black in America.

January 15, 1948, was an extremely transitional time in American history. Harry Truman was president, the Supreme Court banned religion in public schools, the Marshall Plan was enacted, the first LP records were introduced, cars had no seatbelts, there was no Civil Rights bill, there were white and black water fountains in the South, and black people were referred to as colored, Negro, or worse. There was a popular saying among whites and blacks: Im free, white, and 21I can do as I please. However, the concept was only true if you were white.

A glass of beer was only a nickel, Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie still played normal trumpets, and the cheapest seat for a symphony orchestra concert was 60 cents.

A man could be drafted into the armed forces, go to war, and die before he was old enough to vote. Black people had fought in World War II in a segregated army fighting for the same freedoms as whites, but captured German soldiers who had murdered countless white Americans in battle had more rights in the United States during World War II than American black soldiers. A black man could be lynched for interacting with a white woman. If a black person fell sick in the streets, there were only certain hospitals where treatment was available. Consequently, many black people expired before they would ever be admitted to a white only hospital. There were no computers, cell phones, or DVDs in the world in which I drew my first breath.

Next page

![Watt - The 90-day screenplay : [from concept to polish]](/uploads/posts/book/103527/thumbs/watt-the-90-day-screenplay-from-concept-to.jpg)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.