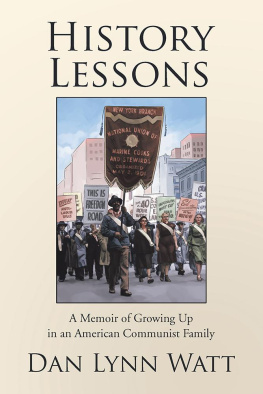

HISTORY

LESSONS

A Memoir of Growing Up

in an American Communist Family

DAN LYNN WATT

Copyright 2017 by Dan Lynn Watt.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017909454

ISBN: Hardcover 978-1-5434-2987-9

Softcover 978-1-5434-2986-2

eBook 978-1-5434-2985-5

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

Rev. date: 07/14/2017

Xlibris

1-888-795-4274

www.Xlibris.com

754665

Contents

For

George Watt (19131994),

Margie Wechsler Watt (19161999),

and Ruth Rosenthal Watt (19151940),

who believed they were going to make a better world

and

Molly Lynn Watt,

who makes the world better every day

May Day Parade, New York City, 1947

New York Daily Worker Photo

Introduction

Making History

At dawn on April 4, 1938, George Watt, fighting as part of the International Brigades for the glorious but doomed cause of the Spanish Republic, reached the west bank of the Ebro River. The river was wide, freezing cold, flowing swiftly at the height of the spring flood. Six men, fleeing from Francos fascist army, knew theyd be imminently discovered. They had to get across the river. They could not find a boat, and the bridges were all blown up.

Three men made a makeshift raft from a barn door. My father and two others said theyd swim. The raft vanished downstream around a bend in the river. The swimmers stripped off their clothes and plunged into the river, letting the current carry them while they swam across. My father and his friend Johnny Gates reached the other side shivering and walked until they came to a road. A jeep came along, carrying two American journalists. The men in the jeep tossed George and Johnny a couple of blankets and asked to hear their story. The journalists were Herbert Matthews of the New York Times and Ernest Hemingway, reporting from Spain for the North American News Agency.

The next day the story appeared on the front page of the Times . All through my childhood, I met people who told me, George Watt is my hero! When he swam the Ebro River, he made the front page of the New York T imes .

After escaping across the Ebro, George was appointed political commissar of the Lincoln Battalion. At twenty-four, he was one of the leading American communists in Spain. He remained a dedicated communist for the next twenty years, including the worst years of anti-communist repression in this country.

My father joined the Young Communist League (YCL) in high school when it led a successful campaign to roll back a two-cent increase in the price of milk in the school cafeteria. My future stepmother, Margie, hitchhiked to West Virginia during a high school vacation to assist striking coal miners. Later she was suspended from Hunter College for leading a one-day peace strikea boycott of classes. My birth mother, Ruth, was arrested at age seventeen for leading a raucous street protest against a speech by Nazi Germanys ambassador at Columbia University.

My parents became communists in the 1930s when the Great Depression exposed the limitations of capitalism. The efforts of political and business elites to provide for the basic needs of the most Americans seemed too littleand too late. Communism offered action to change the status quo. Communist theories cited the Depression as evidence that capitalism was in crisis, perhaps its final crisis, and that the triumph of the working class was inevitable.

In the 1930s communists were part of a progressive coalition, a united front alliance of socialists and liberal New Dealers, labor unions, and civil rights groups, anti-fascist groupsall groups working for social and economic justice, racial equality, a world without exploitation. Not everyone in the united front believed that class struggle was inevitable or that revolution was desirable. But as long as they were working together for common objectives, communists were respected by their collaborators as tough, militant, and effective organizers.

Communists were among the first Americans to oppose the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy. In 1936 a fascist uprising in Spain threatened the democratically elected leftist government of the Spanish republic. The Spanish fascists were massively supported with troops and weapons by Hitler and Mussolini. The leading democraciesBritain, France and the United Statesdeclared neutrality and established an embargo against arms to Spain, which hurt the republic but not the fascists. My father was one of thousands of communists and socialists from many countries who volunteered to fight with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. They had the support of a large proportion of public opinion across the United States.

I am a red diaper baby, a child of communist parents. I was born in March 1940, nine months after my father returned from fighting for the Spanish republic. I grew up knowing that my father was a hero who had risked his life for the cause. My grandparents on both sides, my aunts, and my uncle were communists as well.

I was less than two years old when my father left home to serve in the US Army Air Corps during World War II.

When my father returned home in 1945, my parents expected a bright future for the communist movement. Their movement had hundreds of thousands of supporters across the country, greatly outnumbering the official membership of the party itself, which ran to tens of thousands. Communists and their sympathizers were leaders in some of our countrys largest Labor unions. Communists were influential in the arts as writers, composers, performers, and filmmakers.

I grew up in an optimistic, idealistic family. During my childhood and adolescence, my parents believed they were part of a great historical epochthe epoch of the triumph of the working class. They consciously devoted their lives to making that history come to pass. My parents and most people around them believed that a better society was on the horizon, if only they stayed true to their beliefs and ideals and continued to organize.

History Lessons is almost entirely made up of stories about incidents in my life and my familys life. Through stories about me, my parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles, I seek to illuminate a part of the history 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, as seen through my eyes as a child, adolescent, and young adult.

I grew up trying to straddle two cultures: the rich subculture of idealistic communism and the mainstream culture of midtwentieth-century New York City. I have some of both in this book, as well as some family history that has little to do with politics. I try to capture as best I can the mind-set of the young person I once was.

Sometimes I step back from my own experiences to say a bit more about what was going on in the larger world, as I now perceive it. Occasionally, I reflect on my youthful thinking from the vantage point of my midseventies.

Next page