For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, please contact: permissions@highlights.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

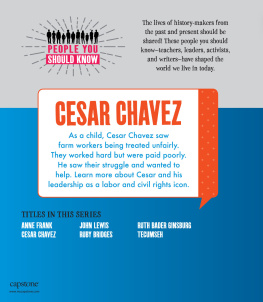

Researching STRIKE! was rewarding and challenging and frustrating. The rewards came in the form of people who opened their doors to me, were patient with my questions, and shared their personal recollections of Csar Chvez and those early days when Filipino Americans began the Delano grape strike. Others sent me information long after my research visit in the hope that it might be useful to my writing (It was!). And still others trusted that I would return borrowed materials that I carried back to my home in Tucson, Arizona. At the same time, I was challenged by the sheer volume of information available about the grape strike and its key Chicano players. So much information was availablefrom FBI files to diaries to correspondence and newspaper clippings. Usually, this is a good problem to have because I love doing research. But I was overwhelmed. Yet I also felt an obligation to sift through it all, even if I knew that most of it would never make it into the final book. Still another challenge was the weather; temperatures that dipped to two below zero made my treks to Detroits Reuther Library a bone-chilling experience for a desert resident like me. I was also frustrated by the lack of acknowledgment of and information about the Filipinos who had begun the strike and who worked for years beside Chvez to see it succeed. First and foremost, I wish to thank the Cesar Chavez Foundation for allowing me access to its collection of materials and for arranging guided tours of La Paz and the Forty Acres. I owe thanks to a great many people who gave of their time and knowledge. They are Paul Chvez, Chvezs middle son and president of the Cesar Chavez Foundation; Bernadette Farinas, Chvezs granddaughter; and Dolores Velasco, widow of UFW secretary-treasurer Pete Velasco; Sheila Geivet and Norberto Vargas for walking the Forty Acres with me and pointing out things that arent included in the history books, such as the small space above the service bay where Chvez hid when threats on his life were made; William LeFevre, reference archivist, Kathleen Emery Schmeling, archivist, and Elizabeth Murray Clemens, audio-visual archivist, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs; Sam Rubin, archivist and educator, John F. Kennedy Library; Melissa Scroggins, librarian, California History and Genealogy Room, Fresno County Public Library; Marc Grossman, Chvezs longtime personal aide and press secretary, and communications director, Cesar Chavez Foundation, for vetting my manuscript and offering a thorough review of the first draft (which was really closer to the twenty-second draft); Pam Muoz Ryan, Kendra Marcus, and especially Lawrence Schimel for Spanish translations when my own Spanish felt too rusty to be trusted; Jim Patrick, Information Services Department, Yuma County Main Library; Johnny Itliong, son of Larry Itliong; Gloria Washington, reference librarian, Kern County Public Library; Aryn Glazier, photo services, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas, Austin; Jan Grenci, reference specialistposters, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress; Guy Porfirio, illustrator, guyporfirio.com; Shelly Longoria, librarian, Palm Springs Public Library; Kay Peterson, Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution; and finally and not least of all my editor, Carolyn P. Yoder, and the entire Calkins Creek teamI couldnt do it without your patience, support, and guidance. Heartfelt thanks to all.

CONTENTS

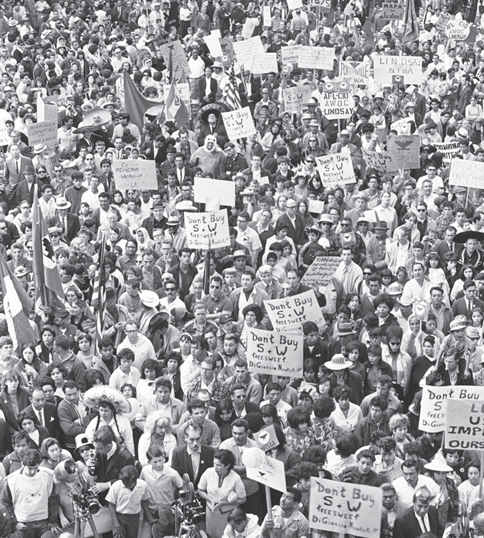

In Spanish and English, strikers took to the picket lines.

During the 1920s and 30s, farm workers tried to organize for better wages and work conditions. Here, a Mexican American picket line forms in Corcoran, California, in 1933.

Delano, el condado de Kern, California, 1965

Delano, Kern County, California, 1965

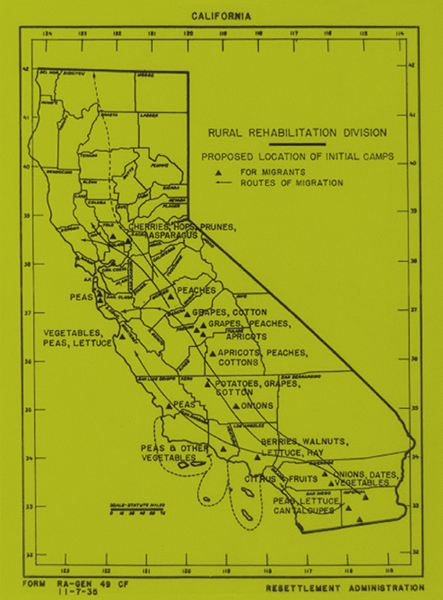

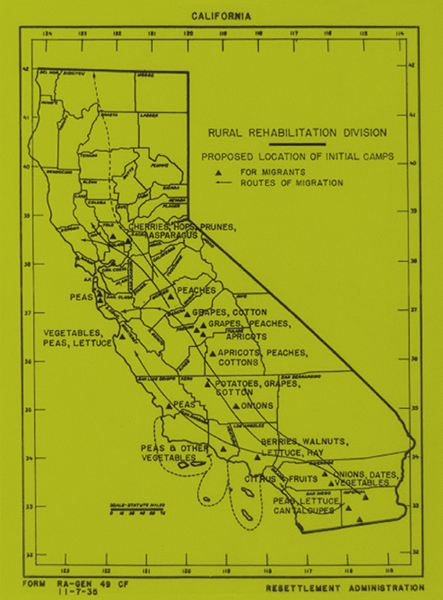

Californias many crops feed the nation and the world.

La huelga de los trabajadores agrcolas Filipinos... comenz esa maana cuando los obreros abandonaron sus herramientas y las sustituyeron por pancartas.

The Filipino farm workers strike... began that morning when workers exchanged their tools for picket signs.

Filipino workers pick lettuce in the Imperial Valley, a desert area east of San Diego and west of Yuma, Arizona.

SEPTEMBER 8, 1965, WAS NO ORDINARY DAY IN DELANO, CALIFORNIA.

The morning sun peeked over the Tehachapi Mountains some sixty-five miles east of this small town at the southern end of the states Central Valley. It cast its warming rays on the areas vast agricultural fields. Almonds. Oranges. Asparagus. Cotton. And grapes: Thompson, Ribier, and Emperor, among other varieties. The grapevines in Delanos vineyards were heavy with fruit, ready to be harvested, boxed, and shipped to market. On a normal harvest day, these vineyards teemed with crews of Filipino farm workers, mostly single men, toiling among the vines. But on this September day, another story was told.

FIELD STRIKE IDLES 1,000 IN KERN FIELDS.

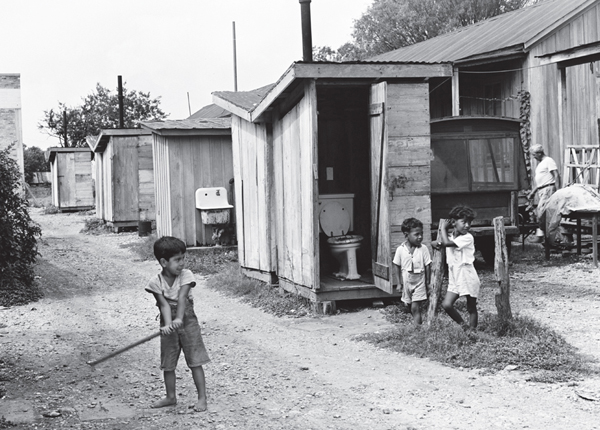

The article in the Fresno Bee didnt tell the entire tale of the Filipino farm workers strike that began that morning when workers exchanged their tools for picket signs to protest unfair wages and poor working and living conditions. The number of strikers varied, depending upon who was asked. Growers say 500 workers are striking, but the Farm Labor Union says about 1,500 field-hands are out. The Fresno Bee settled on one thousand. Whatever their numbers, going out on strikeor refusing to work until their wage demands were methad been an agonizing decision for these farm workers. They were the people who tended the crops and picked the food that ended up in kitchens and on tables across the United States and around the world. Year after year, the grape workers returned to the same vineyards as they followed the annual harvests that started in the irrigated southern deserts of California and moved northward into the fertile Central Valley.