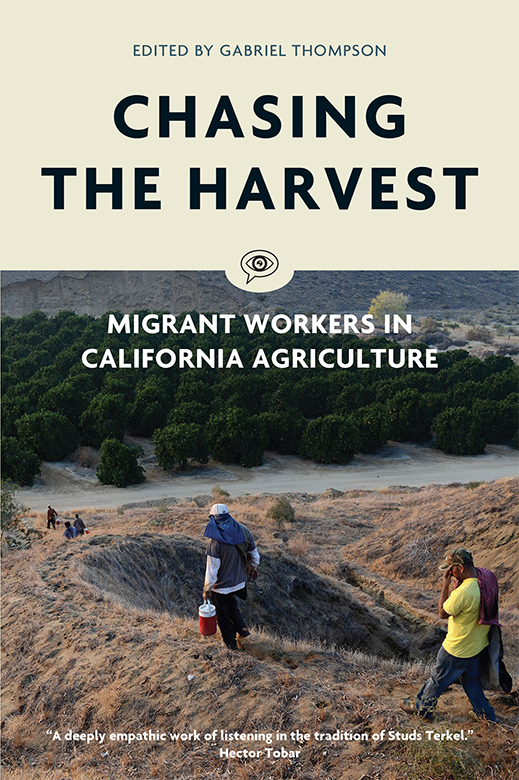

CHASING THE

HARVEST

MIGRANT WORKERS IN

CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE

EDITED BY

GABRIEL THOMPSON

Assistant Editor

ALBERTO REYES MORGAN

Translators

PABLO BAEZA, HALEY CONGER,

PAUL DOMNGUEZ HERNNDEZ, SANDRA GARDUNO,

ARTEMIO GUERRA, MIRIAM HWANG-CARLOS,

MARIA MENDEZ, ALBERTO REYES MORGAN,

LAURA SCHROEDER, BARBARA SHEFFELS,

FEDERICO VARELA

Transcribers

CHARLOTTE EDELSTEIN,

KATIE FIEGENBAUM, ANNIE STINE

Research Editor

ANNIE STINE

Research Assistants

CHARLOTTE EDELSTEIN, MARY BETH MELSO

Copy Editor

MARK WILSON

First published by Verso 2017

Verso and Voice of Witness 2017

Excerpt of Cultivating Fear Human Rights Watch 2012

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-221-0

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-378-1 (HBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-220-3 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-219-7 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thompson, Gabriel, editor.

Title: Chasing the harvest : migrant workers in

California agriculture / edited by Gabriel Thompson.

Description: London ; New York : Verso, 2017. |

Series: Voice of witness

Identifiers: LCCN 2016055800 | ISBN

9781786632210 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Migrant agricultural laborers

CaliforniaCase studies.

Classification: LCC HD1527.C2 C43 2017 | DDC

331.5/4409794dc23

LC record available at

https://lccn.loc.gov/2016055800

Typeset in Garamond by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

VOICE OF WITNESS

Voice of Witness (VOW) is a nonprofit dedicated to fostering a more nuanced, empathy-based understanding of contemporary human rights issues. We do this by amplifying the voices of people most closely affected by injustice in our oral history book series, and by providing curricular and training support to educators and invested communities. Visit voiceofwitness.org for more information.

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & EXECUTIVE EDITOR: Mimi Lok

MANAGING EDITOR: Luke Gerwe

EDUCATION PROGRAM DIRECTOR: Cliff Mayotte

EDUCATION PROGRAM ASSOCIATE: Erin Vong

CURRICULUM SPECIALIST: Claire Kiefer

RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATE: Natalie Catass

CO-FOUNDERS

DAVE EGGERS | MI MI LOK | LOLA VOLLEN |

Founding editor, Voice of | Co-founder, Executive | Founding editor, Voice of |

Witness; co-founder of | Director & Executive Editor, | Witness; founder & Executive |

826 National; founder of | Voice of Witness | Director, The Life After |

Mc Sweeneys Publishing | Exoneration Program |

VOICE OF WITNESS BOARD OF DIRECTORS

IPEK S. BURNETT | KRISTINE LEJA | JILL STAUFFER |

Author; depth psychologist | Chief Development Officer, | Associate Professor of |

Habitat for Humanity, | Philosophy; Director of Peace, |

MIMI LOK | Greater San Francisco | Justice, and Human Rights |

Co-founder, Executive | Concentration, Haverford |

Director & Executive Editor, | NICOLE JANISIEWICZ | College |

Voice of Witness | Attorney, United States Court |

of Appeals for the Ninth | TREVOR STORDAHL |

CHARLES AUTHEMAN | Circuit | Senior Counsel, VIZ Media; |

Co-founder, Labo des | intellectual property attorney |

Histoires |

In August of 1936, an ambitious young novelist named John Steinbeck set out in an old bakery truck for a firsthand look at the lives of Californias migrant farmworkers. Notebook in hand, he toured labor camps and fields, beginning in the Bay Area and heading south. He knew that thousands of Dust Bowl families had come west, fleeing drought and economic devastation. Yet he still wasnt prepared for what he found. In an article for the San Francisco News, he described one family who lived in a cardboard home; when it rained, the structure would slop down into a brown, pulpy mush. Another was holed up inside a tent the color of the ground, with tattered canvas flaps that were held together with bits of rusty baling wire. A third family had constructed a shelter from willow branches and slept under a piece of carpet. Steinbeck heard that a four-year-old boy in the camp he visited had died two weeks earlier of malnutrition. This is the squatters camp, he concluded. Some are a little better, some much worse.

Steinbeck made several more trips in the coming years, doing research for what would become his classic novel, The Grapes of Wrath. The book follows the Joad family, who leave their desiccated farm in Oklahoma carrying little more than dreams of a stable future. They instead find themselves in California contending with one emergency after another. The work in the fields is exhausting. The wages they earn are pitiful. They shelter wherever they cansqualid camps provided by farmers, ditch-bank settlementsuntil chased out by law enforcement. Life is spent shuffling across the state, earning just enough to keep moving along.

On its publication in 1939, Steinbecks novel revealed the struggles of migrant farmworkers in California. But for the people still caught up in the westward migration, the fiction changed very little. Among those migrants was an eleven-year-old boy named Cesar Chavez, whose father had lost the family home in Arizona during the Depression. Chavezs family chased crop harvests up and down Californiapicking carrots in Brawley, thinning lettuce in Salinasat times making homes out of garages and barns. Chavez himself dropped out of school in the eighth grade to work in the fields.

It was the grinding poverty of farmworkers that caused an adult Chavez, in 1962, to walk away from a stable job and move his family to Delano, one of the many sleepy towns in the Central Valley. He had an impossible dream: to organize a union of farmworkers. He didnt have much of a plan, and even less money. But he was stubborn and willing to sacrifice everything for what he would call la causathe cause. Chavez traveled from town to town to spread word about his group, which he originally called the Farmworker Association. Others helped, too. Dolores Huerta, a fiery and fearless activist from Stockton, was often by his side. So was Gilbert Padilla, a World War II veteran like Chavez, who had been born at a California labor camp.