Migrant Citizenship

POLITICS AND CULTURE IN MODERN AMERICA

Series Editors:

Keisha N. Blain, Margot Canaday,

Matthew Lassiter, Stephen Pitti, Thomas J. Sugrue

Volumes in the series narrate and analyze political and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levelslocal, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and popular culture.

MIGRANT CITIZENSHIP

Race, Rights, and Reform in the U.S. Farm Labor Camp Program

Vernica Martnez-Matsuda

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2020 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-0-8122-5229-3

Para mis padres, Esperanza y Liberato Martnez,

que con sus sacrificios me ensearon a luchar por un mundo ms justo,

and for the center of my world, mis amores,

Michael, Joaqun, Lucia, and Oscar Matsuda

CONTENTS

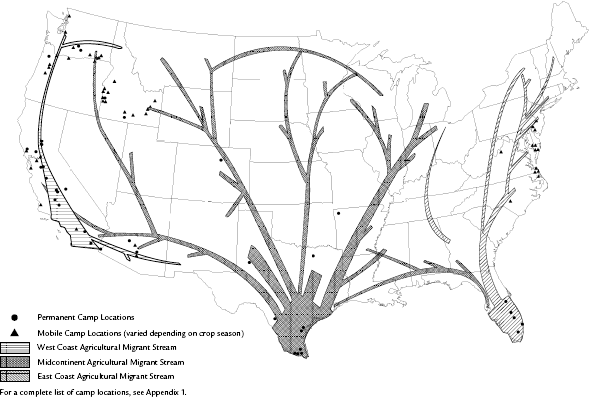

FSA Migratory Labor Camp Locations, July 1942

Map 1. FSA migratory labor camp locations, July 1942. Adapted from Arthur J. Goldberg and Robert C. Goodwin, Hired Farm Workers in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Department of Labor, June 1961), 31. Coordinates for some camp locations were slightly adjusted so as to not overlap. Map prepared by Grace Yixian Zhou.

Introduction

On July 2, 1941, 157 farmworkers residing at the Farm Security Administration (FSA) camp in Weslaco, Texas, signed a petition addressed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt demanding that the U.S. government take responsibility for their well-being by defending their right to decent housing, better wages, and a self Maintainence. The petitioners were contesting the FSAs recent notice of eviction for families who had exceeded the one-year occupancy rule aimed at discouraging permanent residency in the federal migrant camps. The individuals who signed the petition were mainly Mexican American farmworkers from South Texas and white Dust Bowl refugees from the U.S. South and Great Plains. They signed the petition as families, clearly indicated by the Mr. and Mrs. prefix and the grouping of similar surnames on the list. Their appeal declared:

We as United States Citizens of this Free America, and a Bunch of Farmers (Dirt Farmers, not Pencil Pushers) are Now Talking, and are Shooting Streight from the Shoulder, Cold, Undeniable Facts; FIRSTWe are a Bunch of Destitutes; with nowhere to go, Nothing to go on; Secondwe are not Pleading the Cases of the Factory Industry, the Large Farming Industry, nor the Irrigation Industry Inc. but we Judge from the Wages they offer us for our Labor, they must be Somewhat Destitute to. We are yet in Battle and Now Asking for a Chance to as Dirt Farmers, Qualified Citizens, and Eager to work, earn our living, we are Offering our Labor. As to the Up Keep of our little Camp, within our Jurisdiction, we are all trying to keep it Looking Nice, With Flowers, and Eats, in front of our Respective Shelters; we are not a Bunch of Dead-Heads Hobos or Non-Working People, or Trash of the Earth as Probably some might Make-believe us to be. Is the Administration listening? We are Waiting.

The petitioners claims dramatically affirmed their status as hardworking, contributing residents and farm laborers entitled to the protections afforded by the camp program and the privileges of American citizenship. Despite their diverse status as Qualified Citizenswith some identifying as former farmers, others as longtime migrant workersthey came together, as they explained, in a Democratic way to contest the injustice they faced as marginalized, impoverished people. They demanded federal intervention not in the form of charity but as laborers eager to work and to earn their living. Their claims shrewdly demonstrate the interrelated nature of migrant farmworkers struggles for expanded civil rights during the 1930s and 1940s in domestic, labor, and democratic terms.

FSA officials in Washington, D.C., responded to the Weslaco families by upholding the one-year rule yet recommending that the FSA camp manager and local regional director determine the merits of each case before giving families a notice to move. They conceded largely on the grounds of unusually adverse weather conditions seriously affecting the crop seasons in Texas, which meant the evicted families would likely struggle to find work and shelter. The agencys position on the issue, though not readily apparent, also revealed the FSAs own battle for survival. By 1941 the FSA was facing intense conservative pressure from commercial growers and their congressional allies seeking to curtail the agencys social reform mission to eliminate any migrant assistance threatening their labor practices. The FSAs one-year occupancy rule represented the agencys efforts to negotiate the shifting federal politics that, with the onset of World War II and the supposed end of the Great Depression, prioritized farmworkers productive potential over their stability and self-realization. Notwithstanding the FSAs increased role as a labor supplier, the agency remained firmly committed to migrant farmworkers socioeconomic welfare and political equality. As participants in the FSAs camp program, the petitioners knew the agency was on their side. In demanding federal protection and assistance from Roosevelts administration, therefore, they were also defending the FSAs political authority.

This book deepens our understanding of the welfare state as it unfolded under the New Deal by focusing on how migrant farmworkers participation in the FSAs labor camp program challenged the structural forces in agribusiness and rural society that exploited farmworkers as racialized and disenfranchised workers. It also explains how FSA officials fought to extend the promises of New Deal liberalismin more reformist, rights-based, and democratic termsinto the 1940s. I explore familiar discourses about poor peoples relationship to government aid, including concerns over how migrants dependency on the FSA potentially undermined their self-determination. But I also offer a new perspective on how federal, state, and local governments wrestled over the boundaries of citizenship to define who was entitled to public support. FSA officials argued that the migrant problem of the 1930s went far beyond the material consequences of tenant farmers and sharecroppers rapid displacement initiated by a crash in farm prices, increased mechanization, and environmental crisis. A more fundamental problem, they claimed, involved the way that this displacement signaled a narrowing of opportunity and equality in U.S. society.

According to Will W. Alexander, the FSAs chief administrator in 1940, the restlessness and instability produced by migrantsdesperate but vain search for better conditions made a mockery of Democracy. As he explained, under such conditions participation in the affairs of the community and even the enjoyment of the ordinary rights of citizens are virtually impossible. How many of these people attend churches, send their children to school regularly, or even vote? The Great Depression worsened this problem, but it had always existed. Accordingly, the camp program offers an extraordinary lens into how federal agents and migrant farmworkers aimed to resolve the paradox of migrant citizenship and realize a fuller, more inclusive, and vigorous sense of social democracy in the United States.

Next page