First published 1978 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1978 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 78-16796

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Aronson, Dan R.

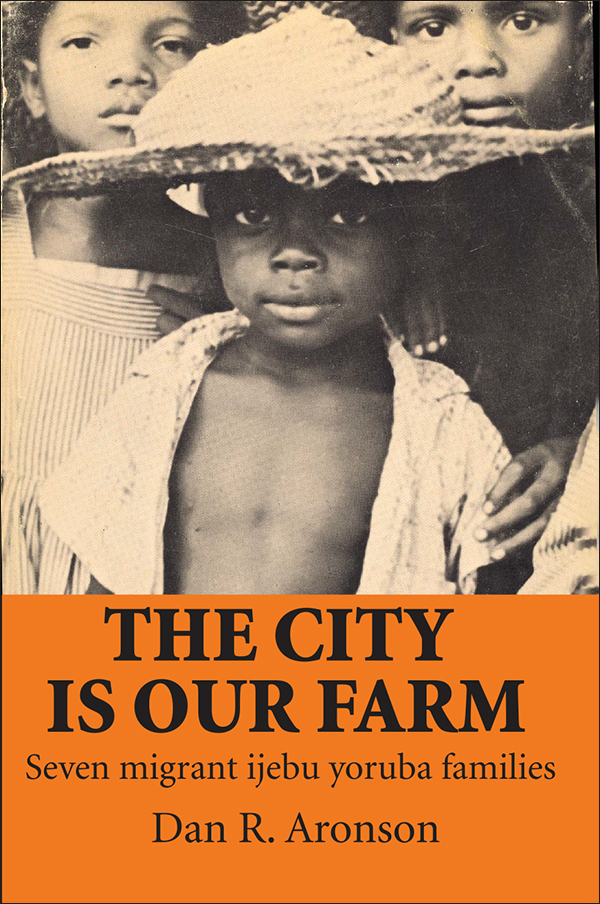

The city is our farm.

Bibliography: p.

1. YorubasSocial conditions. 2. Ibadan, NigeriaSocial conditions. 3. Detribalization. I. Title.

DT513.A74 1978 301.361 78-16796

ISBN 0-87073-563-2

ISBN 13: 978-0-87073-563-9 (pbk)

Preface to the Paperback Edition

As Nigeria goes, so goes Africa. With one fourth of black Africas population and an economy that dwarfs all the others north of the Republic of South Africa, Nigeria presents all of Africas problems and prospects. Pumping about two million barrels of oil a day, she derives an enormous income that allows her people to hope that they will overcome the pervasive poverty that they have shared with other Third World peoples until now. Eager participants in modern economic, educational, and social activities, her citizens have set a clear course for the achievement of national prosperity. With her leaders born in her small towns and villages, her vision is one committed in theory to sharing the benefits of prosperity across the countryside. Elsewhere in Africa people look to Nigeria for an image of the self-assuredness, cultural pride, economic strength and social vitality that their own leaders declaim as the virtues of a meaningful national career.

At the same time, Nigerian development is beset with difficulties. Her efforts must be spread over a vast population, overwhelmingly rural, divided by language and ethnicity, oriented to disparate goals. Her dependence upon external markets and supplies keeps her vulnerable to outsiders decisions. Control of bloated budgets gives her small political and economic lite the tools for consolidating ostentatious class privilege. Conflicting priorities and the scarcity of management skills have destructively delayed attention even to some of her most obvious development needs. It remains possible that, when her oil runs out, Nigeria will be as debilitated as other African countries that presently have her problems but not her potential.

In the turbulence created by these forces, individual Nigerians find their way as best they can. Some grow cash crops, or migrate to where cash crops are grown, in order to make a living. Hundreds of thousands have been induced to migrate to urban areas, because the opportunities to get up, as Nigerians would say, are so heavily concentrated there.

This book is about such migrants. The research experience on which it is based is now over a dozen years old. The situation of migration it reports, however, persists and indeed includes more people than ever. And because of the importance of this situation to anthropologists, the publisher of this book has agreed to present it in paperback form.

Like their counterparts all over the world, the Nigerian migrants have the double burden of making new lives for themselves using their own resources, and of giving meaning to the lives that they are leading in unfamiliar and uncertain surroundings. How can you judge if the move will be successful will you find enough to eat? Who will help you? How will you relate to your new neighbors, or to the kinsmen you leave behind? What will become of your attachments to home? Will your children share your sense of belonging, and will they in their turn migrate away from your area?

The Ijebu Yoruba about whom this book has been written have found their own answers to these questions. But their dilemmas resonate in many other areas of the world: Students at the University of Papua New Guinea, for instance, have found in my reporting of the Ijebu Yoruba experience a direct and vivid reflection of their own.

It is in this worldwide searching out of the dimensions and the meanings of human behavior that anthropology continues to play a special role among the social sciences. Social life can be captured by numerical studies only imperfectly, while interpreting the meaning of what are otherwise mere facts is a task which anthropological analysts have always made central.

Indeed, it is in the work of interpreting social life that anthropologists and the ordinary people they study make common cause. Anthropology provides one version of the experience that its subjects have themselves undergone. While anthropologists have often only translated that experience for outsiders to inspect, now we can also encourage the dialogue between insiders and the sensible interpretations of their own lives that they struggle to achieve.

Here, then, are re-presented the lives of seven ordinary families who themselves are conscious of the turbulence in their society. What is offered is one interpretation that will inevitably be placed alongside others. I hope that the personalization of the study encourages other individuals, Ijebus and outsiders, to reflect on how they themselves would make sense of the experience presented and on how they would act in the situations that are described. And I hope that the paperbound edition of this book will be useful to students.

Preface

More than most other social sciences, anthropologyx is an individual enterprise. Along the way, however, the anthropologist piles up debts to teachers, supporting agencies, family and colleagues, and particularly to the people among whom he works. I am no exception to this pattern.

As an undergraduate at Wesleyan University, my teachers David McAllester and David Swift introduced me to the humanistic study of culture. Lloyd Fallers, Sol Tax, Edward Shils, Aristide Zolberg, and my doctoral supervisor, Robert LeVine, trained me in social science and in African studies at the University of Chicago. This study tries to mediate both the humanistic and the social science backgrounds that I have.

This book is based upon research carried out in Nigeria from January, 1966 to May, 1967. In particular, the family studies were done between November of 1966 and the following May. Fieldwork was made possible by the Foreign Area Fellowship Program of the American Council of Learned Societies and the Social Science Research Council, and by a supplementary grant from the Committee on African Studies of the University of Chicago. The Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research provided help in a variety of ways before and during my sojourn in Ibadan.

Among my colleagues and students it is difficult to record the names of all those who, knowing it or not, contributed to the preparation of this material. Professors Robert LeVine, Robert Mitchell, Olu Okediji, Philip Foster, James OConnell, and especially Akin Mabogunje encouraged my thinking during the fieldwork. Philip Salzman, Myron Echenberg, Lawrence Nwakwesi and Judith Smith have stimulated my work at McGill University, and the students in Anthropology 315 have served as sounding-boards for many notions incorporated here. Ade Kukoyi kindly read the manuscript and made many helpful suggestions.