PLUVICULTURE

THE ART OF MAKING IT RAIN

The Amazing, Mysterious, True Life of Charles Mallory Hatfield

THE RAIN WIZARD

LARRY DANE BRIMNER

CALKINS CREEK

AN IMPRINT OF HIGHLIGHTS

Honesdale, Pennsylvania

FOR CAROLYN P. YODER

CONTENTS

DROUGHT

Charles Mallory Hatfields camp, on a ridge above the northern shore of Morena Reservoir in the backcountry of San Diego County, California, resembled a military outpost. In a way, that is exactly what it was on New Years Day 1916. Surrounded by a perimeter fence, two white munitions tents glinted in the morning sun. One served as an office and sleeping quarters for the two men manning the camp: Hatfield, age forty, and his twenty-five-year-old brother Joel. The other was used to store their supplies and at least twenty-three secret chemicals. An observation tower, wrapped in heavy, black tar paper for privacy, had been erected a few yards away. The platform stood a dozen or so feet above the ground. Charles Hatfield, wearing a fedora and carrying a rifle, could be seen from time to time patrolling the fence, intent on keeping unwanted visitors at a distance.

A camp similar to the one Hatfield set up above the shore of Morena Reservoir. This one dates from 1924. Note the tar-paper wrap around the tower. Hatfield was intent on keeping his process and chemical formula secret.

His was not a usual war. His was a fight against drought that plagued the West and brought crop failure to farmers throughout much of the United States. Charles Hatfield was a rainmaker, although he bristled at the term. He never claimed to make rain. He was, instead, a rain inducer or coaxer. He used his secret concoction of chemicals to attract clouds and compel them to give up their moisture.

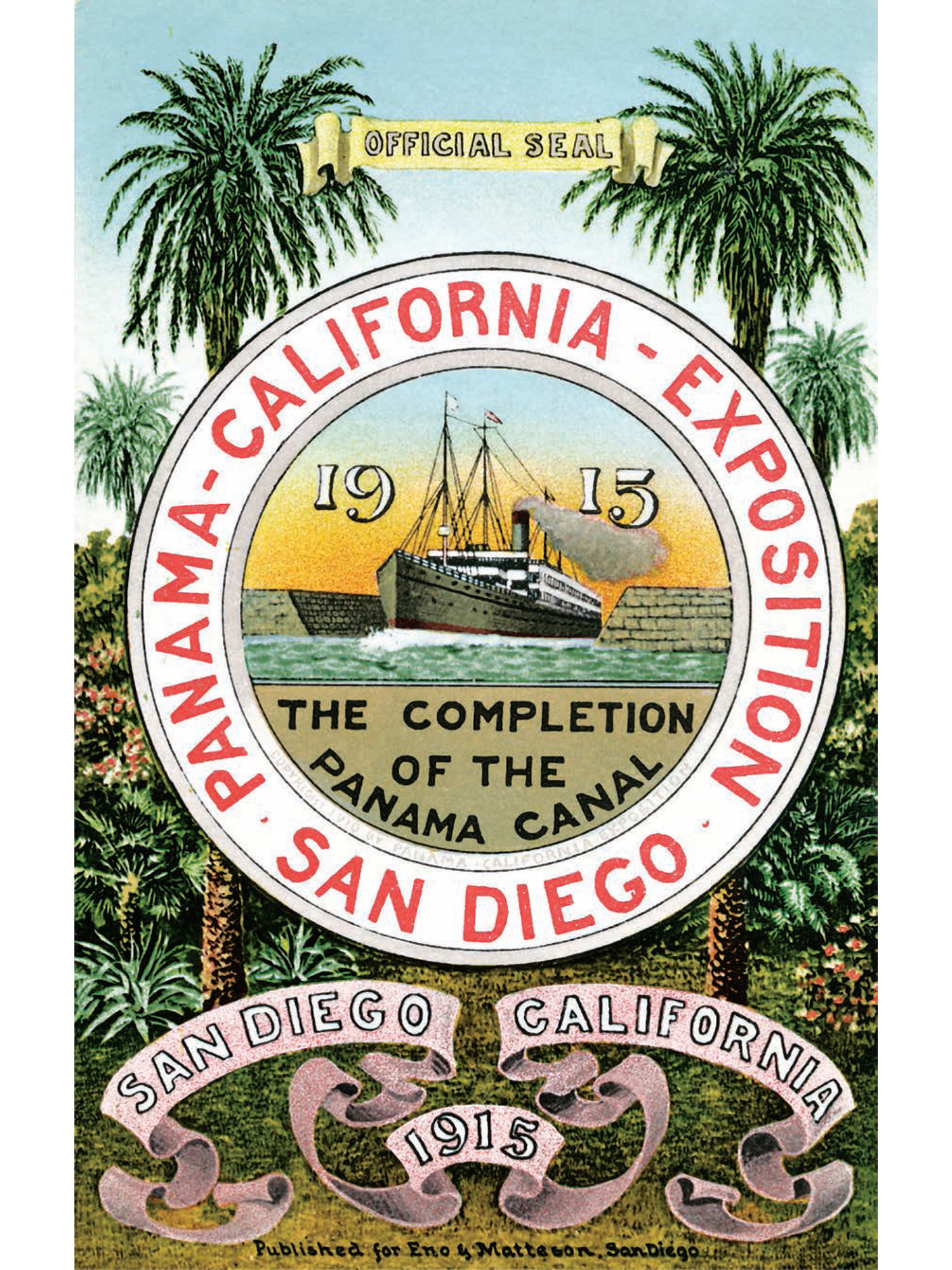

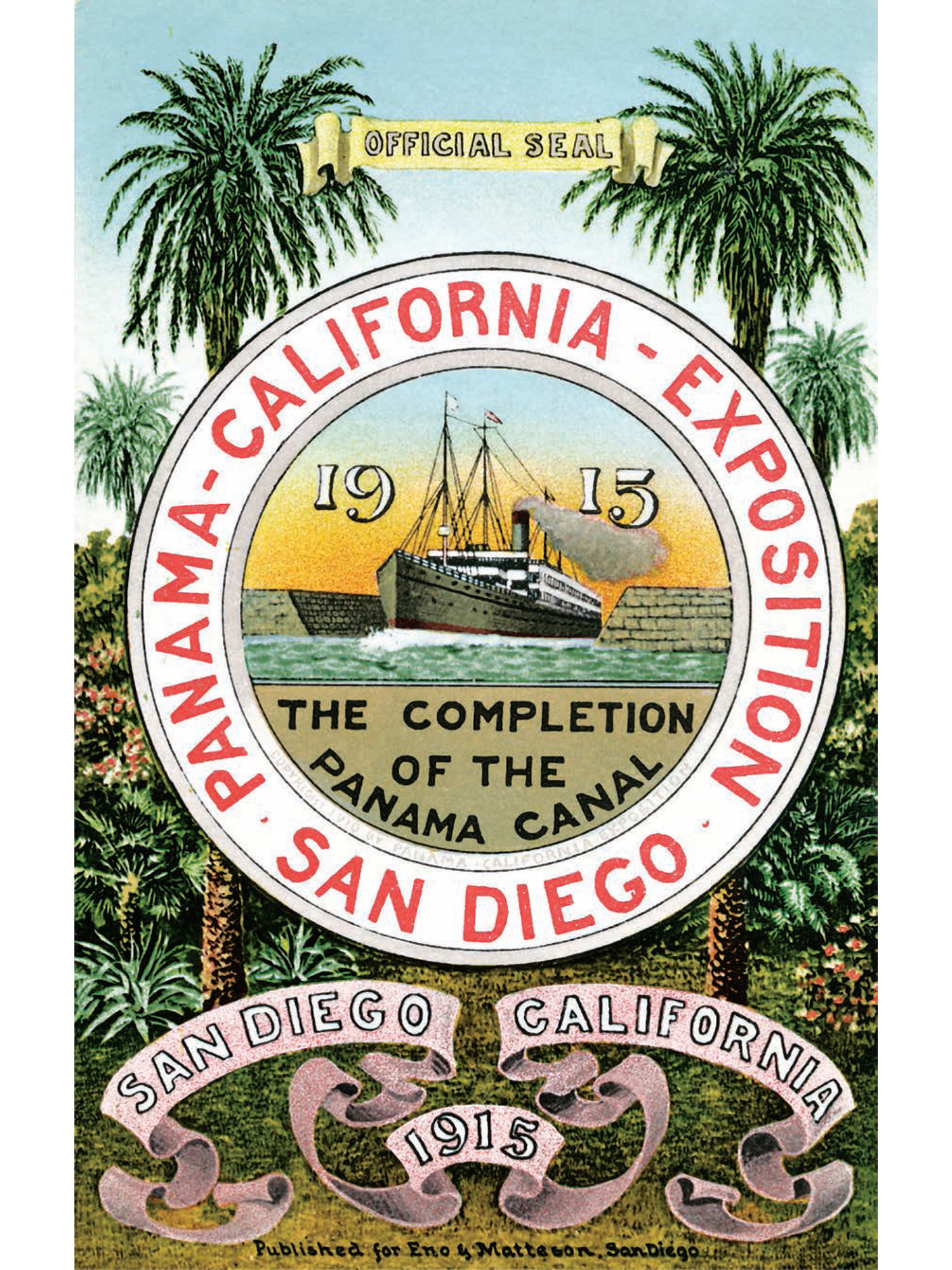

In early December 1915, Hatfield received a telegram from San Diegos city council. They wanted to talk. At the time, the city was hosting the Panama-California Exposition to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. The event was also meant to show off San Diego as the first U.S. port of call that ships heading north would reach after passing westbound through the canal. Political leaders and real estate moguls alike hoped the exposition would present the city at its finest to draw new residents and investors to the area. San Diego had dreams of overtaking Los Angeles as Californias most populated city. To accommodate more people, San Diegos leaders realized they would need a reliable and abundant source of water. Its average rainfall of around ten inches each year means it is a semiarid desert. The area historically had experienced long periods of drought. Although it had a system of aqueducts and man-made lakes in place, few if any of these reservoirs had ever been filled to capacity. Certainly, the citys Morena Reservoir, begun in 1897 and completed in 1912, had never received enough rainfall to fill it. With five billion gallons of water retained behind its dam, the reservoir was sitting at only one-third full.

Despite the citys close-to-normal rainfall pattern and nearly average precipitation totals for the year, San Diegos leaders began Considering the citys rainfall totals, the article wasnt exactly accurate. However, the San Diego Union and its sister newspaper, the Evening Tribune, were owned by John D. Spreckels. At one time or another, he counted among his local holdings large swaths of real estate, the citys electric street-railway system, the Southern California Mountain Water Company (which built Morena Reservoir and was the citys largest, privately owned utility until he sold it to the city for $4 million in 1914), and several downtown buildings. A millionaire many times over and son of Claus Spreckels, who had made a fortune in sugar, John Spreckels didnt hesitate to use his newspapers to promote his views and for his own financial gain. Spreckels was one of two of the most prominent and powerful businessmen in San Diego. The other was Elisha Babcock, who owned four thousand acres of oceanfront property and built, along with Spreckels, the citys grandest hotel, the Hotel del Coronado. Spreckelss views and his newspapers opinions were always considered by local politicians. Both Spreckels and Babcock knew there was money to be made if only San Diego had water, and lots of it, and talk of drought was one way to spur the citys political leaders to look for sources other than those already in use.

Almost immediately, Shelley Higgins, the assistant city attorney, echoed the Union, saying the water supply in the reservoirs had dwindled to an alarming degree. One reservoir was described as being as shallow as a pane of glass. Rural ranchers regularly drew off much, if not most, of the water flowing in the San Diego River, leaving it a mere trickle by the time it reached the ocean. Terence B. Cosgrove, the city attorney, filed a lawsuit against the ranchers. He claimed that on the basis of an old grant from the king of Spain, the full flow of the river belonged to the city and not to rural landowners. Legal battles over water in the American Southwest were common, and plaintiffs often suggested their wells were dry even when they werent.

The Panama-California Exposition was meant to show off the port city of San Diego at its finest. Because the exposition featured exhibits from other countries, it was renamed the Panama-California International Exposition in 1916.

The recent surge in growth had placed new demands on San Diegos water supply, and this worried businessmen like Spreckels and Babcock; therefore, it worried politicians. The towns future depended on water. With plans to extend the exposition another year and memories of a seven-year drought in the 1890s, the city council seemed close to desperation.

A down-on-his-luck Englishman, Frederick Fred A. Binney, believed in science and in mankinds ability to mold and control nature. He had lost his own citrus orchard a short distance east of San Diego to a winter dry spell. Having followed Charles Hatfields rainmaking career over the years, he was convinced that Hatfield held the scientific key to ending drought. With a keen sense of how he might make some money, he appointed himself Hatfields promoter and began taking out advertisements for Hatfields services in newspapers throughout California. Hatfield, who always prided himself on his integrity and honesty, accepted the help despite Binneys shady reputation. Binney was known in real estate circles for being less than honest, sometimes placing his crude, handmade For Sale signs on property that wasnt his to sell. Expecting to receive a percentage of any deals Hatfield struck, Binney contacted the city council in 1912 on behalf of the rain-coaxer. He was turned away. His reputation had preceded him, and he met with a skeptical audience.

Next page