I want to first express my deep appreciation to Raul Ruiz, Gloria Arellanes, and Rosalio Muoz for their support of this project and their patience.

I want to thank my editors and staff at the University of California Press, including Niels Hooper, Eric Schmidt, Kim Hogeland, and Bradley Depew, for their assistance and helpful suggestions. Special thanks to Lynne Withey and Sheila Levine. The two anonymous readers for the press provided sage advice for improving the manuscript. In addition, I am grateful to Ellen McCracken for checking the Spanish used in the text. Additional thanks to Amber Workman, who helped me format the text.

I want to also thank my colleague Professor George Lipsitz for his support and encouragement of this project.

A number of photographers and archivists kindly gave permission to use the photos that appear in this book. They are acknowledged in the captions.

I especially want to thank the Guggenheim Foundation for awarding me a Guggenheim Fellowship, which was crucial at the commencement of this project. For additional funding support, I also want to thank the Academic Senate at the University of CaliforniaSanta Barbara and the Chicano Studies Institute.

Finally, as always, I am thankful to my wonderful and supportive family: Ellen, Giuliana, and Carlo. I hope and pray for many more years with them, God willing.

Introduction

Viva la Raza! Chicano Power!

I first heard these stirring words when I arrived in San Jose, California, in the fall of 1969. I had come from El Paso, Texas, to begin teaching as an instructor of history at San Jose State College (later San Jose State University). The rallying cry was my introduction to the Chicano movement. It had barely surfaced in El Paso, so what I encountered in San Jose was mind-boggling. I had heard about the movement, of course, and, in preparing a class on Chicano history, I had read up on it, discovering some of the emerging journals, such as El Grito, and movement newspapers in California. But none of this research prepared me for what I would personally experience.

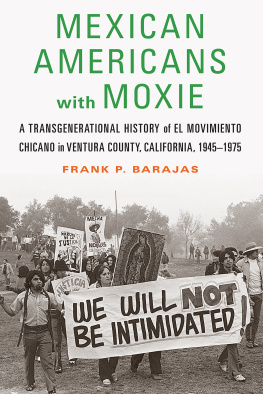

I met militant Chicano students, Chicano studies faculty, and members of the Black Berets, the likes of whom I had never before encountered. At first, I felt distant from them, and even a bit scared. But as I got to know some of these activists better, I came to identify with them and with the issues they were passionate about. I participated in marches and rallies against injustice to Chicanos in the schools and the community and especially against police abuse. (I had never seen such huge and intimidating copsall whiteas I did in San Jose!) It did not take me long to identify as Chicano and to align myself with the movement.

Of course, I knew the term Chicano. I had first encountered it in my all-boys Catholic high school in El Paso in the early 1960s. Mexican American kids from the hard-core barrio of south El Paso used it to assert pride. I lived, literally, on the other side of the tracks, in an ethnically mixed lower-middle-class neighborhood, and did not use the term myself but admired the students who did. Now, in the late 1960s, the term was connected to the Chicano movement and used politically by a new generation to express the militant demands for civil rights, ethnic pride, and community empowerment.

Indeed, this is my generationthe Chicano generation. I too came of age in the 1960s and became politically conscious, first as a liberal Democrat and then as a participant in the Chicano movement. As a graduate student interested in Chicano history and as a professor of Chicano studies, I supported a variety of movement actions both on campuses and in the community. Through this oral history of Chicano movement activists, I have learned even more about my generational history.

It was the movement that provided the opportunity for me to advance my education, eventually obtaining a PhD in history and joining a university faculty. I owe much to the movement, and, as a professor of Chicano studies and a student of Chicano history, I aim to pass on to others the legacy of this struggle for social justice and ethnic respect. The cry Chicano Power! still resonates within me and is very much a part of who I have become.

I began this collaborative oral history, or testimonio, and the interviews with three key participants in the movement in Los Angeles in the early 1990s: Raul Ruiz, Gloria Arellanes, and Rosalio Muoz. The text was more than twenty years in preparation. For this delay, I apologize to Raul, Gloria, and Rosalio.

This study is a collective testimonio of three major activists in the Chicano movement in Los Angeles during its heyday in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The years from 1965 to 1975 are especially critical in the struggle for civil rights, renewed identity, and empowerment by a new generation of Mexican Americans who revived the older barrio term Chicano as a symbol of new ethnic awareness and political power. The term testimonio, or testimony, comes out of a rich Latin American tradition of producing oral histories, or oral memoirs, through the collaboration of political activists or revolutionaries with progressive scholars or journalists. The result is an oral testimony of the life, struggles, and experiences of activists who might not have written their own stories. While they focus on one life, testimonios are also collective in nature because they address collective struggles. Ruiz, Arellanes, and Muoz are leaders, but they are group-centered leaders.

But more than just narrating life stories, testimonios are intended to educate others and inspire them to continue the struggles of the storytellers. Testimonios possess praxes: for readers to read, reflect, and act. That is what makes them a powerful teaching vehicle.