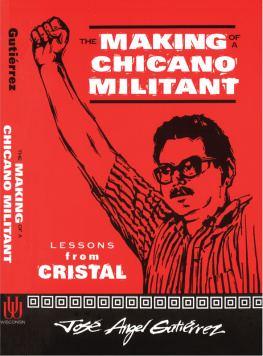

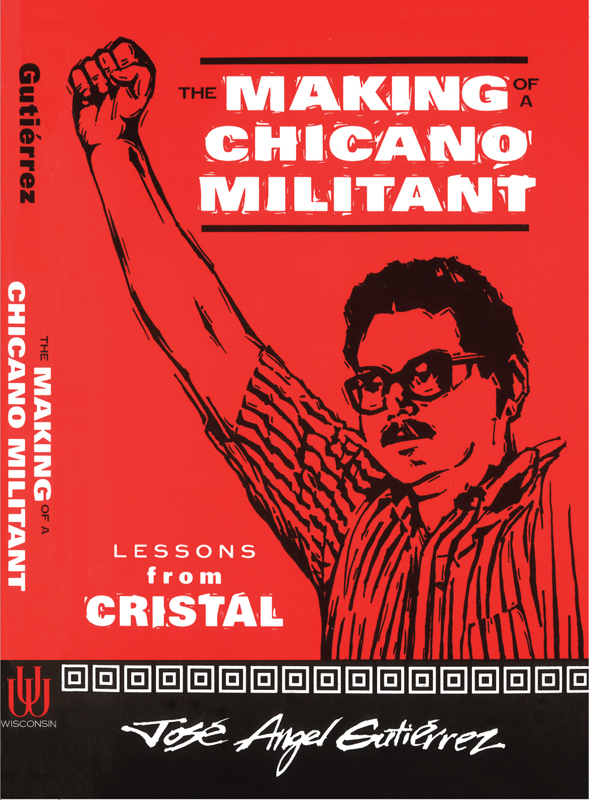

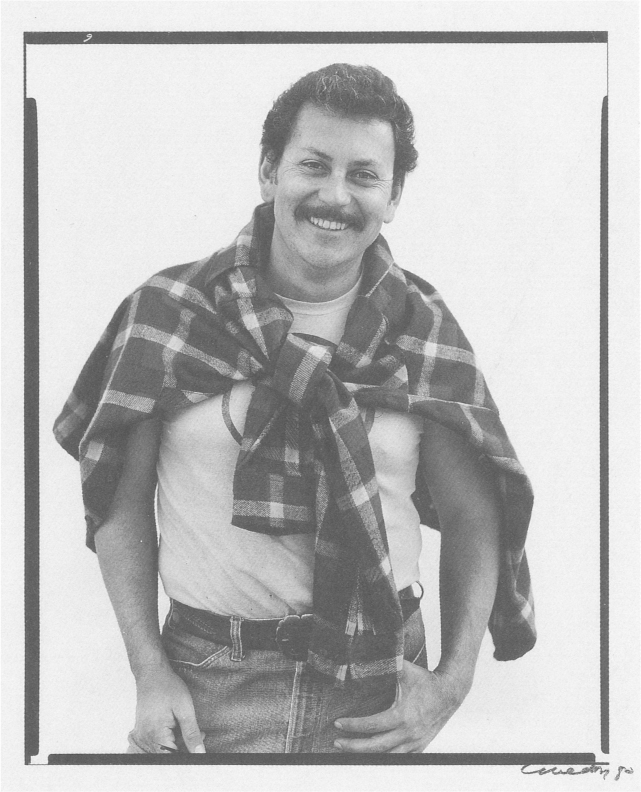

Jos Angel Gutirrez. Photograph by Richard Avedon. Crystal City, Texas, 1979.

The Making of a Chicano Militant

Lessons from Cristal

Jos Angel Gutirrez

THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN PRESS

Wisconsin Studies in Autobiography

WILLIAM L. ANDREWS

General Editor

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

London WC2E 8LU, United Kingdom

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 1998

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseor conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to

Frontispiece: Jos Angel Gutirrez. Copyright 1979 Richard Avedon.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gutirrez, Jos Angel.

The making of a Chicano militant: lessons from Cristal / Jos Angel Gutirrez

352 pp. cm.(Wisconsin studies in autobiography)

Includes index.

ISBN 0-299-15984-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Gutirrez, Jos Angel. 2. Mexican AmericansTexasCrystal CityBiography

3. Political ActivistsTexasCrystal CityBiography. 4. Crystal City

(Tex.)Ethnic relations.nt.

I. Title. II. Series.

F394.C83G88 1998

976.4437dc21

[B] 98-13866

ISBN 978-0-299-15984-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-15983-2 (e-book)

Para Adrian, Tozi, Olin, Avina, Lina,

Andrea y Clavel, mis hijos

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

Over the years, I often would burn and chafe at reading two types of written material: that written about Chicanos, and that written which ignored the Chicano presence and contribution. I often would ask myself how and why such trash could be printed about us and without us. But, I didnt write.

Later, as the Chicano movement and I became the focus of some of these writings, I not only burned and chafed while reading the material, I also became enraged at the content. I could not believe that it was us or me they were writing about, I did not recognize the social movement or the person. But, I didnt write.

My rationalization was that I was too busy making things happen during the Chicano movement to take time to write. And, it takes a lot of time to write. I did manage to keep a diary and notes from time to time.

On occasion during the 1970s and into the 1980s, I would give a speech or engage in conversation, and the anti-Chicano content of these magazine and newspaper articles, books, and documentaries would come up. My responses to this type of material invariably led someone in the audience, or the partner in conversation, to implore me to write that up so that other Chicanos can learn the real truth. I recall specifically such early prodding from Hank Lopez, Bill Crane, Lupe Angiano, Rudy Acua, Armando Gutirrez, Tatcho Mindiola, Irma Mireles, Reymundo and Maria Marin, Irene Blea, Armando Navarro, Charon DAiello, Charlie Cotrell, Elizabeth Betita Martinez, my former spouse, Luz Bazan Gutirrez, my current spouse, Gloria Garza Gutirrez, and my older children, Adrian, Tozi, and Olin. While visiting Hank Lopez at his home in upstate New York in the early 1970s, I recall outlining with him over many bottles of beer the plot of a novel he and I would write based on my activities in South Texas. He wanted to develop the character of a super Chicano hero in a serial novel who would liberate South Texas. I surmised that I was the prototype for his Chicano hero. Lopez dropped this idea in favor of another contemporary theme involving the takeover of Manhattan by black militants. Afro 6 is the book he ultimately wrote. Neither he nor I ever got around to writing about the Chicano hero and the takeover of South Texas before he died. During the late 1970s, Tatcho Mindiola and I discussed with the novelist Max Martinez the possibility of having him write my biography. After a heated argument between Max and me about his all-consuming interest with sex and violence in my lifestyle, I declined. Over the years, countless people in Cristal have asked me when I would write THE real story about our struggle in that community. But, I didnt write.

I was still too busy with the Chicano movement, governing Zavala County, Texas, and running La Raza Unida Party in eighteen states and the District of Columbia. I barely managed to keep records and recordings of happenings, meetings, and speeches in the 1970s.

Finally, I was made to write by the demands of seeking promotion and tenure at Western Oregon State College in 1981, and later, in 1993, at the University of Texas at Arlington. I wrote and had published articles in scholarly journals, coauthored a book, written book chapters and reviews, essays, and several newspaper editorials in both English and Spanish. At the beginning of this decade, I began earnestly researching and writing several manuscripts, mostly for academic audiences.

Irene Blea, the prolific scholar and director of Chicano Studies at California State University at Los Angeles, called me shortly after the death of Cesar Chavez in 1993, urging me to think about writing an autobiography. She offered to write my story if I didnt have the time or inclination to undertake it myself. This time, I was ready for the idea and began the labor, thanks to this last prodding by her. Most recently, during the summer of 1996, while embroiled in an employment dispute at my present university over the leadership of the Center for Mexican American Studies that I founded there in 1993, Ricardo Gonzales suggested we collaborate and write a biography of my struggles. This is not that manuscript, but it is a beginning narrative of some aspects of my life.

While attending the National Association for Chicano and Chicana Studies conference in Spokane, Washington in 1995, I met with several editors of academic presses exhibiting their works at the gathering. Rosalie Robertson of the University of Wisconsin Press took particular interest in me and my life story. We discussed the various manuscripts I had under production, she was most interested in this manuscript and suggested I send a copy of the first chapters to Bill Andrews, the editor of this series. I did. Shortly thereafter, I received a letter from him encouraging me to continue the manuscript to completion, along with a contract from Rosalie Robertson. From that moment on, not a day went by that I was not dictating to a microcassette recorder, or word processing on a laptop, home computer, or office computer. Even while camping in northern New Mexico or the rolling hills of Wyoming, or staying in a Motel 6 with the smaller children of the family during the summer months of 1995 and 1996, I kept writing and rewriting. In December, 1996, when the completed manuscript was mailed off, my wife, children, and I celebrated with my favorite pastime, a backyard cookout. On that occasion my two youngest daughters, Clavel Amariz and Andrea Lucia, then ages six and eight, asked if this meant they now could yell and scream while playing in the house and if now I would have time to read them stories instead of admonishing them with