For Beginners LLC

155 Main Street, Suite 211

Danbury, CT 06810 USA

www.forbeginnersbooks.com

Text and Illustrations: 2016 Maceo Montoya

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

A For Beginners Documentary Comic Book

Copyright 2016

Cataloging-in-Publication information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN-13 # 978-1-939994-64-6 Trade

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Beginners and Beginners Documentary Comic Books are published by For Beginners LLC.

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

FOR ANGIE CHABRAM,

WHO KEEPS THROWING PUNCHES.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY ILAN STAVANS

Democracy is rowdy and boisterous and insatiable. Its strength lies in the fact that it is always unfinished, a work in progress in which history is always being reassessed by constant social change. This means that ideas and emblems and figures go in and out of fashion.

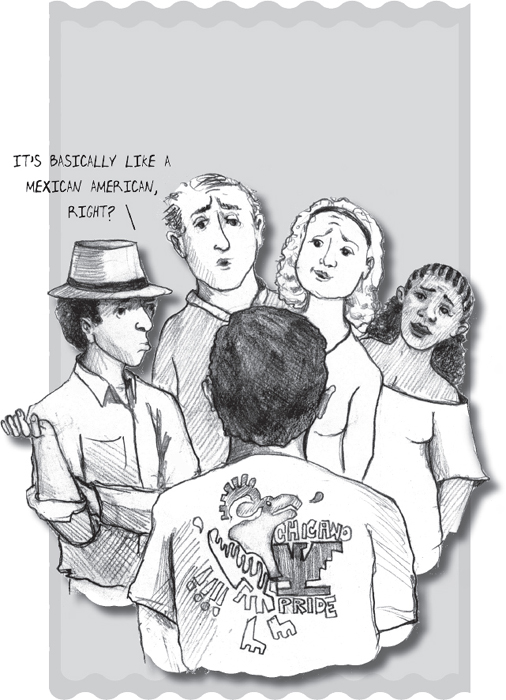

Take the term Chicano. Once a moniker symbolizing empowerment, it seems to have undergone an eclipse. Mexican Americans use it only sparingly today, often to refer to the Chicano Movement, also known as El Movimiento, the upheaval that sought to reconfigure, during the Civil Rights era, their place in the tapestry that is the United States. It seldom shows up to describe the present.

To some degree, this is because as a minority, Mexican Americans have become part of a larger identity rubric, Latinos, encompassing them as well as millions of others with origins in Latin America and the Caribbean (Salvadorans, Dominicans, Colombians, Cubans, Puerto Ricans, et al). But there are other reasons: unlike Black Liberation, the Chicano Movement, in truth, was less about race than about class. And a few of its leaders, Csar Chvez among them, made what in hindsight appear to be tactical mistakes. A few were against immigration, for instance, which is the equivalent of being against their own origins. And their connection with Mexico, where many of them traced their roots, was faulty, disengaged, and even negligent.

It pains me deeply that the Civil Rights era continues to be seen, by most people, in black and white, not in full color. That is, the plight of other ethnic groups, including Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos, whose struggle for self-determination is equally important, is seldom considered integral to it. In the last few decades, streets, schools, and community centers in the Southwest have been named after Chvez and other Chicano historical figures. Yet their achievements have gone largely undigested by the nation as a whole. Chvez himself said that in his fight he drew strength from despair but, unfortunately, that despair is seldom acknowledged in any meaningful way in the public sphere. He believed that history will judge societies and their institutions ... by how effective they respond to the needs of the poor and the helpless. Well, on that front as well, the United States leaves much to be desired.

Maceo Montoya is intent on reawakening us. He is the son of a leading Chicano activist and artist, Malaquias Montoya, and a sibling of poet Andrs Montoya, author of the award-winning The Iceworker Sings, who died tragically, of leukemia, at the age of 31. A painter as well as scholar, he has produced a spirited For Beginners book that pays tribute to the legacy of Mexican illustrator Eduardo del Ro, aka Rius, by looking at El Movimiento with fresh eyes. It mixes highbrow and pop culture in engaging, thought-provoking ways. At its core, it is, in my view, a family affair, an attempt by Professor Montoya to reconsider the past his forebears shaped, a past that lives inside him and the rest of us, and whose place in the future is still up for grabs.

The Chicano Movement might look dead, Montoya suggests, but its spins continue to define us, whether we acknowledge it or not. It is time to fashion its ideals back to the present.

Mexican-born educator, author, and cultural critic Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. He is the author of numerous book-length works, including Latino U.S.A.: A Cartoon History; the editor of numerous others, including The Norton Anthology of Latino Literature; a prolific contributor to scholarly journals and anthologies; and a popular television and radio commentator.

PROLOGUE

I grew up in a Chicano home, which is to say, my family considered the Chicano Movement to be very much alive, and its important events and leaders were mentioned with great frequency and seemingly at every opportunity. As a child in the 1980s and early '90s, I was exposed (often dragged) to countless political rallies and cultural events, and everyone else at these functions seemed to share the same base of knowledge about the Chicano Movement, not only why it was important and who was involved, but also why its goal to create a more just and equitable society continued to be relevant. So I have to admit that when I finally ventured off into the wider world, it was somewhat of a surprise to learn that whenever I mentioned the Chicano Movement, or even the word Chicano, most people didn't know what I was talking about.

As the heyday of the Chicano Movement, roughly 19651975, fades further into history, and as more and more of its important figures pass on, so too does knowledge of its significance. Thus, this book is a small attempt to stave off historical amnesia. It seeks to shed light on the multifaceted civil rights struggle that formed the Chicano Movement. Just as African Americans in the 1960s fought to end centuries of racism, discrimination, and injustice, so did Mexican Americans. From California to Texas and well into the Midwest and even the East Coast, young and old emerged from the shadows to demand their rightful place in American society. The Chicano Movement, also known as

Next page