University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada, 89557 USA

Copyright 2011 by University of Nevada Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

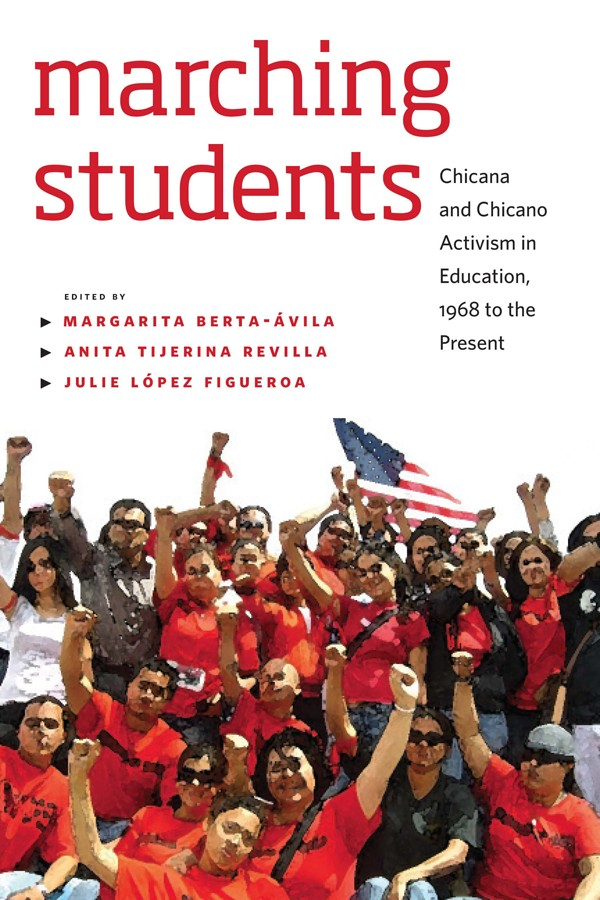

Marching students: Chicana and Chicano activism in education, 1968 to the present / edited by Margarita Berta-vila, Anita Tijerina Revilla, and Julie Lpez Figueroa.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87417-841-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Hispanic American studentsSocial conditions. 2. Educational equalizationUnited States. 3. Student movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. United StatesEthnic relations. I. Berta-vila, Margarita, 1972 II. Tijerina Revilla, Anita, 1973 III. Lpez Figueroa, Julie, 1969

LC2670.M36 2011

373.18'108968'72073dc22

2010035066

ISBN 978-0-87417-861-6 (ebook)

To Csar, Liliana, Santiago, Delia, Dee Dee,

Brenda, Destiny, Rae Ana, Michael, Anthony, Chito,

Macedonio, Maria, Marina, Raul, and Alfredo

ILLUSTRATIONS

FOREWORD

Forty years ago, during the month of March 1968, Mexican American high school students shocked the city of Los Angeles and the nation when thousands of them walked out of the segregated public schools located in the eastside barrios of the city. I was one of the college student activists who marched with them through the streets of East Los Angeles to peacefully protest the racism and educational inequality we faced in the schools.

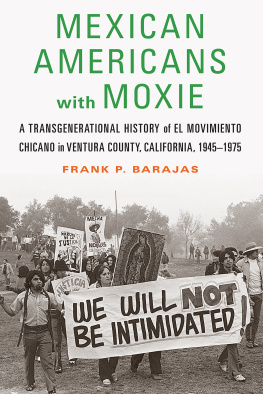

The walkouts lasted for a week and a half and disrupted the nations largest public-school system and captured front-page headlines and national attention. More than ten thousand students participated, including students from the predominantly African American Thomas Jefferson High School in South Central Los Angeles who walked out in solidarity with us.

Three months after the walkouts, I was one of thirteen walkout organizers who were indicted for conspiracy to disrupt the Los Angeles city school system, the largest in the nation. At the time, I was a first-year graduate student and the president of my campus chapter of the United Mexican American Students. I was arrested in the early-morning hours while hard at work on a term paper due for one of my graduate seminars. The trauma my family and I were forced to endure during my arrest and subsequent imprisonment was a life-changing experience for me.

The thirteen of us who were indicted faced sixty-six years in prison if convicted of the conspiracy charges. It took two years for our case to be decided by the California State Appellate Court. The court finally ruled that we were innocent of the conspiracy charges by virtue of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granting freedom of speech.

The walkouts were the first major mass dramatic protest against racism and educational inequality ever staged by Mexican Americans in the history of the United States. It was carried out in the nonviolent protest tradition of the Civil Rights movement. Its historical significance was similar to the 1960 black student sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina. As the Greensboro student protest fueled the flames of the civil rights struggle in the South, the East Los Angeles walkouts ignited the emergence of the Mexican American civil rights movementwhich came to be known as the Chicano movementthroughout the southwestern United States.

The Chicana/o movement opened doors for equal opportunity in higher education to young people who had been systematically excluded and led to the creation of Chicana/o studies departments and programs throughout the nation. It also contributed to equal opportunity in employment for Mexican Americans and other Latinas/os. It produced thousands of professionals that included writers, poets, artists, filmmakers, lawyers, teachers, medical doctors, health workers, and social workers as well as hundreds of community and labor organizers and political leaders at the local, state, and national levels of government.

The movement also resulted in a generation of scholar activists deeply committed to playing a role in the struggle for civil and human rights and social justice in our society. The scholars and activists represented in this volume are outstanding examples of those who continue to follow the path charted by the 1960s generation. The work they have produced for this volume places the 1968 walkouts and the Chicana/o civil rights movement in historical context. Their exemplary work provides a critical understanding of, and insight into, the continuing struggle being waged by Latina/os for educational equality in the United States.

I am pleased the editors of this volume decided to commemorate those historic walkouts with this outstanding collection of essays.

Carlos Muoz Jr.

Professor Emeritus, University of California, Berkeley

PREFACE

This book seeks to commemorate the 1968 Chicana/o student walkouts, or blowouts, that occurred throughout the Southwest. Birthed from the Chicana/o movimientos, the student blowouts in East Los Angeles were a visible social critique of the ways traditional education underserved and marginalized Chicana/os. With careful planning led by students, approximately ten thousand Chicana/o students walked out of classes on March 1, 1968, to protest educational inequity. Within the process of protest for a more inclusive pedagogy, the student blowouts served as a reminder that identity politics continue to mediate the quality of education students receive.

This is a timely book that not only presents an analysis of the walkouts of 1968 but also traces a development in various sectors of education to the present. This edited volume highlights and draws parallels between the students who marched in 1968, 2006, and the present. Most importantly, the essays explore what these kinds of student movements indicate about the state of our society. As a result, the contributors in this volume ground their scholarship in critical resistance, queer, critical race, and Chicana feminist theories to frame and to ask new and provocative questions on Chicana/o identity and activism as they relate to education and the student protests of today. We explore Chicana/o identity and activism through student and community marches, flag waving, and chanting that have been stereotyped as radical instead of progressive. Oftentimes, this portrayal has impeded dialogue and the exchange of potentially beneficial ideas. In terms of theories and pedagogies in education, highlighting the transformative contributions those with a Chicana/o consciousness have made, and continue to make, is long overdue. As the fortieth anniversary for the East L.A. Blowouts approached, we thought it timely and necessary to collect the stories and work of our colleagues to show that the struggle for better education for Chicanas/os and Latinas/os is constant and fierce.

Lastly, we would like to acknowledge how the idea for this book developed. We presented our work with colleague Luis Urrieta at a panel at the American Educational Research Association conference titled Chicana/o Activism and Education: Theories and Pedagogies of Trans/formation. The panel was part of the Critical Educators for Social Justice Symposium, and it was chaired by Dr. Antonia Darder, a scholar who has led the way and mentored many of us on this path toward creating social change with education. After the presentation, it was solidified. Even though we come from many walks of life with similarities and differences across gender, sexuality, race/ethnicity, age, and citizenship/immigration, it became critical that as educators we unite with the same intentto use education as a tool for transformation. Thus we were inspired to share our stories and research collectively and publish this work.