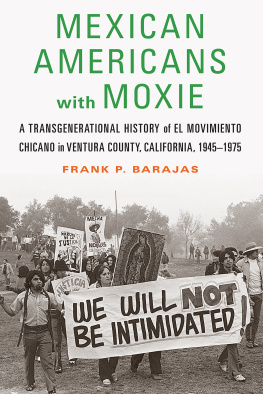

Youth, elders, liberals, militants, Mexicanos, and Chicanos all populate these pages, a tribute to the multifaceted nature of the Chicano movement. In the end, the book stands as a valuable testament to the enduring coraje (the courage and anger) of los de abajo (the suppressed) to fight for justice.

Lorena Oropeza, author of The King of Adobe: Reies Lpez Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement

Frank Barajas mixes the best of labor history, social and ethnic history, and solid storytelling to explain how Mexican workers, students, and other activists sought a piece of the good life in one of Californias most important agricultural counties.

Josh Sides, author of Erotic City: Sexual Revolutions and the Making of Modern San Francisco

[This] is an impressive reassessment of the Chicano and Chicana movement through a transgenerational approach that beautifully captures the shift in political consciousness of Mexicans and Mexican Americans.... This book is a refreshing reminder that both generations can learn from each other to make a better world for all.

Jos M. Alamillo, author of Deportes: The Making of a Sporting Mexican Diaspora

Mexican Americans with Moxie

A Transgenerational History of El Movimiento Chicano in Ventura County, California, 19451975

Frank P. Barajas

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2021 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

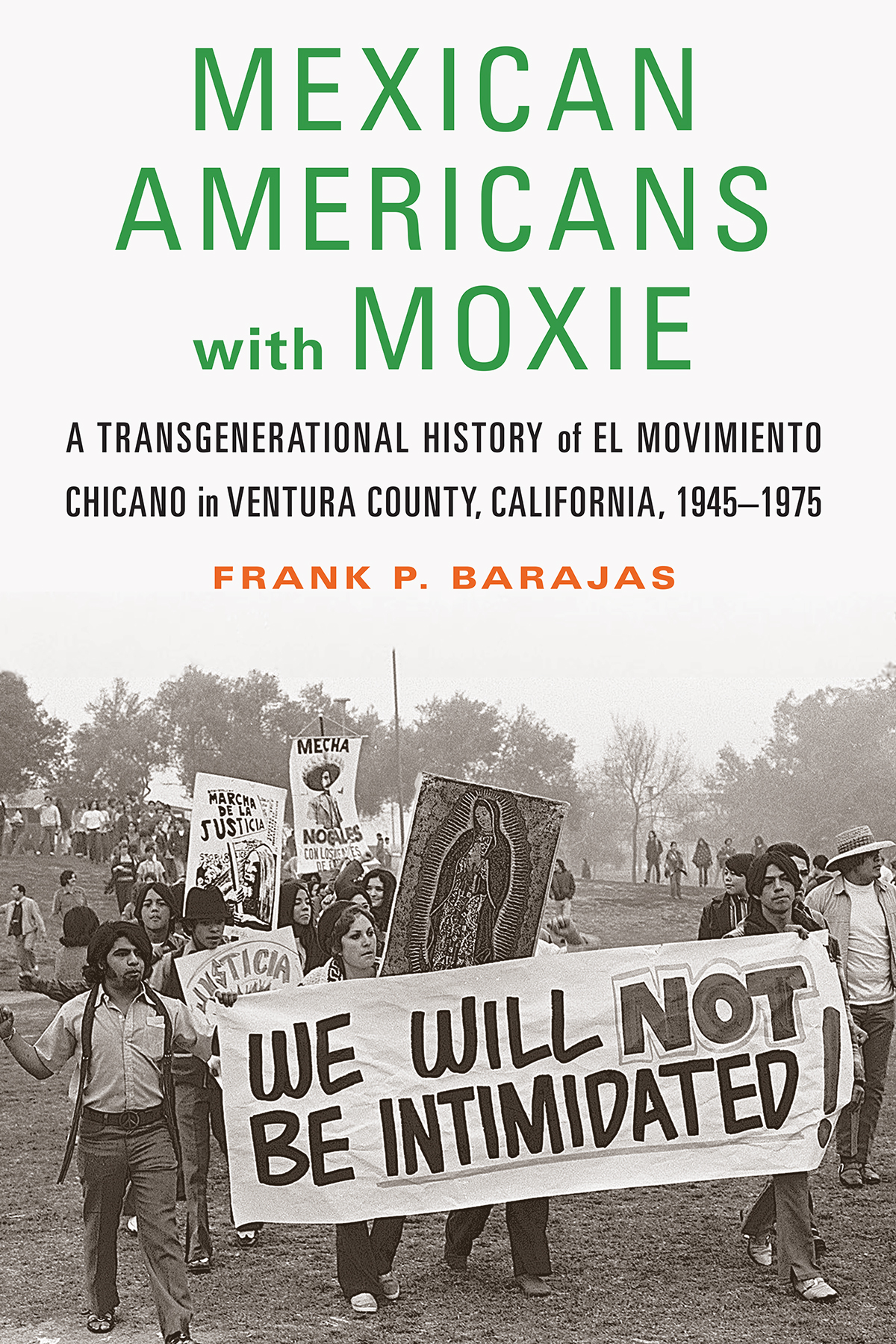

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image Luis C. Garza.

Author photo courtesy of the author.

An earlier version of chapter 2 appeared as Community and Measured Militancy: The Ventura County Community Service Organization, 19581968 in Southern California Quarterly 96, no. 3 (Fall 2014): 31349. Parts of the conclusion originally appeared as An Invading Army: A Civil Gang Injunction in a Southern California Chicana/o Community in Latino Studies 5, no. 4 (2007): 393417.

All rights reserved.

Publication of this volume was assisted by the Offices of the President, Provost, and the Dean of the School of the Arts and Sciences, as well as the Departments of Chicana/o Studies and History at California State University Channel Islands.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barajas, Frank P., 1964 author.

Title: Mexican Americans with moxie: a transgenerational history of el Movimiento Chicano in Ventura County, California, 19451975 / Frank P. Barajas.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020038861

ISBN 9781496207630 (hardback)

ISBN 9781496227348 (epub)

ISBN 9781496227362 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Chicano movementCaliforniaVentura County. | Mexican AmericansCaliforniaVentura CountyPolitics and government20th century. | Mexican AmericansCaliforniaVentura CountySocial conditions. | Mexican AmericansCaliforniaVentura CountyEthnic identity. | Ventura County (Calif.)Ethnic relations.

Classification: LCC F 870. M 5 B 36 2021 | DDC 305.868/72079492dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038861

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

There is that great proverbthat until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter. That did not come to me until much later. Once I realized that, I had to be a writer. I had to be that historian. Its not one mans job. Its not one persons job. But it is something we have to do, so that the story of the hunt will also reflect the agony, the travailthe bravery, even, of the lions.

Chinua Achebe

Contents

From the United Farm Workers ( UFW ) Boycott Office in Delano, California, Jessica Govea, twenty-four, examined a clipping of a full-page advertisement in the Ventura County Star-Free Press sent to her by Ray Ortiz, the unions organizer in the city of Oxnard. Published on January 30, 1971, after the In Support of Cesar Chavez title, it declared, WE ARE MEXICAN-AMERICANS , non-farmworkers who support Cesar Chavez and the work he is doing in [sic] behalf of the farmworkers. The 240 signatories denounced the attacks of the agricultural industry that branded their champion a deceitful Marxist revolutionary. They also consisted largely, but not exclusively, of Spanish-surnamed residentsmany born before World War II, others afterward. The jaccuse intrigued Govea. In her reply letter, she thanked Ortiz and closed with Looks like you guys are doing some good boycott work. Viva la Causa!

Three years later, after months of underground organizing on the part of gritty UFW apio-fresa (celery-strawberry) harvesters from Salinas with local compeers, a strawberry strike erupted in Ventura County on May 26, 1974. As part of a migrant syndicate, ethnic Mexican farmworkers on the Oxnard Plain demanded the improved work conditions won by brethren at the sister Salinas Valley operations of the Dave Walsh Companyone dollar for a tray of strawberries, a twenty-cent increase.

Three days later UFW president Chvez, forty-seven, traveled from Delano to lead a protest march of two thousand people through the streets of the La Colonia barrio of Oxnard. Then, after a Mass at La Virgin de Guadalupe Church, Chvez, followed by his fans, strutted to nearby Colonia Park to deliver a speech. Once there he indicted Ventura County law enforcementjudges, the district attorney, sheriff, and OPD with collusion in the service of the agricultural industry. He exclaimed that of all the places where the UFW had fought for the rights of farmworkers, Ventura County was the most viciousperhaps worse than Texas, with its Rangers terrorism.

Within these abridged narratives exist a composite of historical subjects. In the first, the sponsors of the newspaper ad instantly proclaimed their discrete status as MEXICAN-AMERICANS , non-farmworkers, even though most of the listed people were the progeny of agricultural workers, if not long-time Mexican migrant residents themselves. Within this cohort also existed two generational groups: one born before World War II that came of age prior to the 1960s, and the other subsequently. Historically, ethnic Mexicans born before 1945 have been labeled the Mexican American generation. I label activist youth born afterward the Chicana-Chicano generation. The former primarily approached their adulthood during the decades of the Great Depression, World War II, and conflict in Korea. The latter, in their youth, witnessed in one form or another the nations escalated intervention in the civil war of Vietnam, the assassinations of iconic political and civil rights leaders, as well as momentous marches and demonstrations. Another demographic dimension of the people recognized was that, before settling in Ventura County, many lived as migrants, not only from Mexicowith and without authorized residencybut also places outside of Southern California, such as the valleys of Salinas and San Joaquin, and South Texas.

Moreover, the same year that self-proclaimed Mexican American residents took out their newspaper ad, conga player Andre Baeza of the band El Chicano opened a live performance of its Brown Sound hit Viva Tirado with the proclamation By the way, were all Chicanos! Hence I argue that a collection of people from the Mexican American and Chicana-Chicano generations defined El Movimiento (the Chicano movement) in Ventura County. Certainly, not all ethnic Mexicans identified themselves as Chicanas-Chicanos,

Next page