Contents

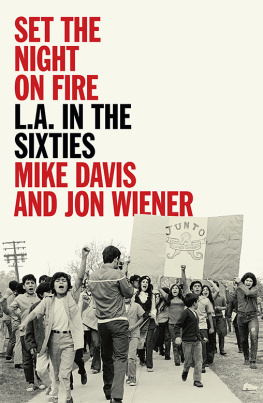

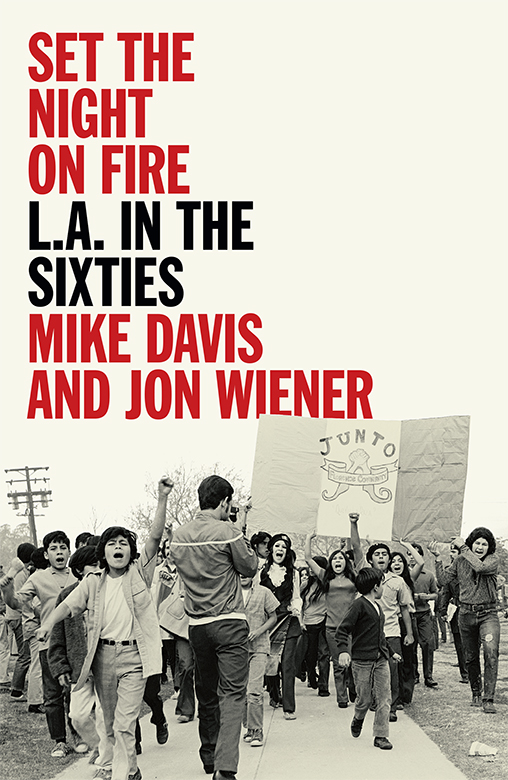

Set the Night on Fire

Set the Night

on Fire

L.A. in the Sixties

Mike Davis

and

Jon Wiener

First published by Verso 2020

Mike Davis and Jon Wiener 2020

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Chapter 1, Setting the Agenda, was originally published in

New Left Review 108, NovDec 2017.

Chapter 21, Riot Nights on the Sunset Strip, was originally published in Labour/

Le Travail 59, Spring 2007, and then in In Praise of Barbarians, by Mike Davis

(Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2007).

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-022-7

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-024-1 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-023-4 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Fournier by MJ&N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

For Levi Kingston and Geri Silva whom I admire

more than words can express and for Alessandra

whose love saved me.

MD

For Judy

my Angeleno.

JW

The time to hesitate is through

No time to wallow in the mire

Try to set the night on fire.

The Doors, Light My Fire

The song was number one in 1967. In many ways the Doors were the quintessential LA group of the sixties.

In 1968, Buick offered them $75,000 to use the song in a commercial. When lead singer Jim Morrison found out, he called the company and said he would personally smash a Buick on TV with a sledgehammer if they used the song. Jim Morrison died in 1971; since then, drummer John Densmore has made sure that the Doors songs are not sold for commercials.

Densmore told us in an interview for this book: The seeds of civil rights and the peace movement and feminism were planted in the sixties. And they are big seeds. Maybe they take fifty or a hundred years to reach fruition. So stop complaining, and get out your watering can. Thats my rap.

Contents

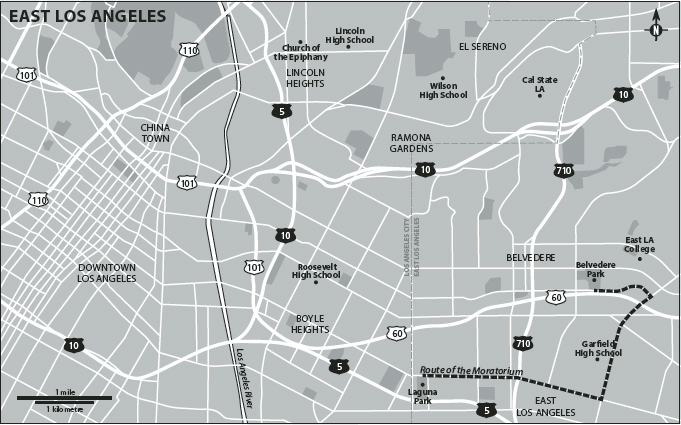

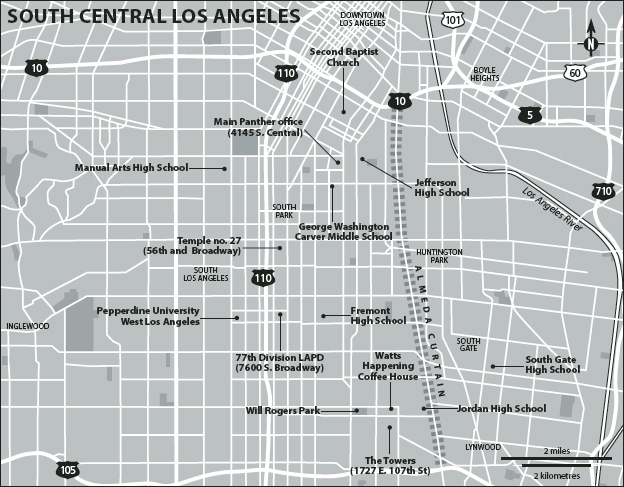

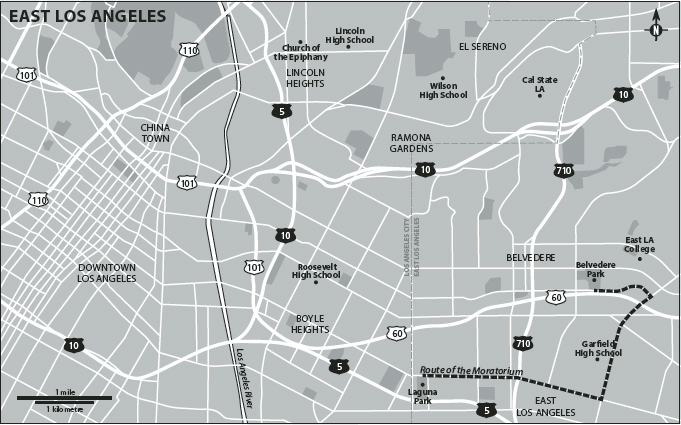

I n August 1965 thousands of young Black people in Watts set fire to the illusion that Los Angeles was a youth paradise. Since the debut of the TV show 77 Sunset Strip in 1958, followed by the first of the Gidget romance films in 1959 and then the Beach Boys Surfin USA in 1963, teenagers in the rest of the country had become intoxicated with images of the endless summer that supposedly defined adolescence in Southern California. Edited out of utopia was the existence of a rapidly growing population of more than 1 million people of African, Asian, and Mexican ancestry. Their kids were restricted to a handful of beaches; everywhere else, they risked arrest by local cops or beatings by white gangs. As a result Black surfers were almost as rare in L.A. as unicorns. Economic opportunity was also rationed. During the first half of the Sixties, hundreds of brand-new college classrooms beckoned to white kids with an offer of free higher education, while factories and construction sites begged for more workers. But failing inner-city high schools with extreme dropout rates reduced the college admissions of Black and brown youth to a small trickle. Despite virtually full employment for whites, Black youth joblessness dramatically increased, as did the index of residential segregation. If these were truly golden years of opportunity for white teenagers, their counterparts in South Central and East L.A. faced bleak, ultimately unendurable futures. The history of their revolts constitutes the core narrative of this book.

But L.A.s streets and campuses in the Sixties also provided stages for many other groups to assert demands for free speech, equality, peace and justice. Initially these protests tended to be one-issue campaigns, but the grinding forces of repressionabove all the Vietnam draft and the LAPDdrew them together in formal and informal alliances. Thus LGBT activists coordinated actions with youth activists in protest of police and sheriffs dragnets on Sunset Strip, in turn making Free Huey one of their demands. When Black and Chicano high school kids blew out their campuses in 196869, several thousand white students walked out in solidarity. A brutal LAPD attack on thousands of middle-class antiwar protesters at the Century Plaza Hotel in 1967 hastened the development of a biracial coalition supporting Tom Bradley, a liberal Black council member, in his crusade to wrest City Hall from right-wing populist Sam Yorty. In the same period the antiwar movement joined hands with the Black Panthers to form Californias unique Peace and Freedom Party. There are many other examples. By 1968, as a result, the movement resembled the music of LA free jazz pianist Horace Tapscotts Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra: simultaneous solos together with unified crescendos. Historians of Sixties protests have rarely studied the reciprocal influences and interactions across such broad spectrum of constituencies, and these linkages are too often neglected in memoirs, but they provide a principal terrain of our analysis.

Periodization is often fraught for historians, who understand the necessity of temporal frameworks but also their artificiality. The Sixties in L.A., however, have obvious bookends. We start in 1960 because that year saw the appearance of social forces that would coalesce into the movements of the era, along with the emergence of a new agenda for social change, especially around what might be called the issue of issues: racial segregation. In L.A. those developments overlapped with the beginning of the regime of Sam Yorty, elected mayor in 1961. 1973, on the other hand, marked not only the end of protest in the streets but also the defeat of Yorty and the advent of the efficient, pro-business administration of Tom Bradley.

There were also three important turning points that subdivide the long decade. 1963 was a roller-coaster year that witnessed the first: the rise and fall of the United Civil Rights Committee, the most important attempt to integrate housing, schools and jobs in L.A. through nonviolent protest and negotiation. Only Detroit produced a larger and more ambitious civil rights united front during what contemporaries called the Birmingham Summer. In California it brought passage of the states first Fair Housing Actrepealed by referendum the following year in an outburst of white backlash. 1965, of course, saw the second turning point, the so-called Watts Riots. The third was in 1969, which began as a year of hope with a strong coalition of white liberals, Blacks and newly minted Chicanos supporting Bradley for mayor. He led the polls until election eve, when Yorty counterattacked with a vicious barrage of racist and red-baiting appeals to white voters. Bradleys defeat foreclosed, at least for the foreseeable future, any concessions to the citys minorities or liberal voters. Moreover, it was immediately followed by sinister campaigns, involving the FBI, the district attorneys office, and both the LAPD and LA County Sheriffs, to destroy the Panthers, Brown Berets and other radical groups. This is the true context underlying the creeping sense of dread and imminent chaos famously evoked by Joan Didion in her 1979 essay collection,