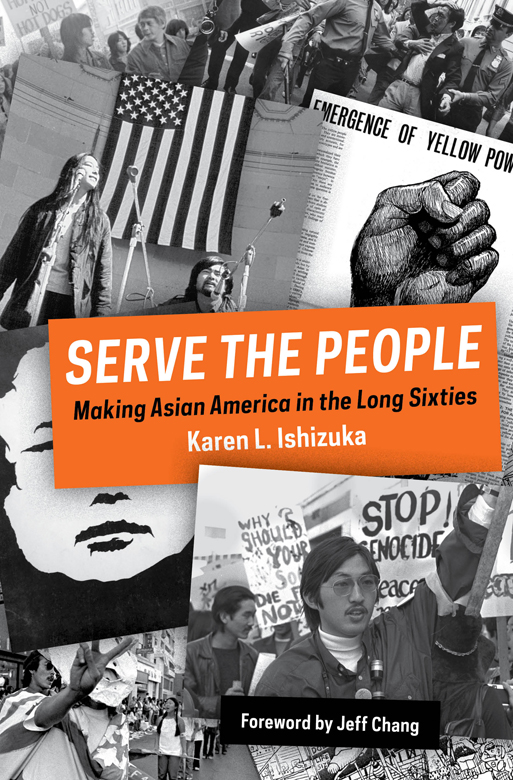

Karen L. Ishizuka

Karen L. Ishizuka 2016

Foreword

by Jeff Chang

Consider the Asian American at the dawn of her historyskipping past the toddling and babbling, leaping straight into loud youthful rebellion. There was a time, Karen Ishizuka reminds us, when the term Asian American was not merely a demographic category, but a fight you were picking with the world, an argument you intended to draw out with indifferent or hostile parties. In 1969, Asian America was about young people, mostly second-, third-, or even fourth-generation in the United States, waking to their in-betweennessbetween Black and white, migrant and citizen, silence and screamingand finding collective release in a mass upwelling of feeling.

To say that the notion of Asian America was a social construct is to ignore the beautiful, sometimes destructive energies of this great becoming, the passionate ideas, the dazzling creations, and the abject failures of a multitude in motion. Serve the People is a history of what it felt like to live in those timesfrom the intensity and ecstasy of the period of discovery to the terror and betrayal of the spent revolution. It is the story of imaginations afirea grand and necessarily naive project to enlarge possibility in a time of change.

Asian America was born in an age of countercultural ferment. There is a familiar developmental arc to countercultures, a narrative in three acts. Act One speaks of emergence: the sense of something big, the intoxicating musk of sweaty rooms, the explosion of ideas, the taking to the streets. Act Two is maturation: its the time of manifestos, standing-room-only meetings, confrontations with authority, the building of institutions, the anticipation of power. Act Three is the period of backlash and/or transfiguration: the revolution is televised, the empire strikes back, the pressure drops, the witch hunts, the factions, the meltdown, the crossover, the spectacle. All this happened.

But Asian America was more than just a counterculture. By the mid 1970s, it was embarrassing to call oneself a hippie, still is. But Asian American has come to symbolize much more and much lessabout which more shortlythan its advocates ever intended. We have come to call the moment that Ishizuka captures the Asian American movement because after it we saw ourselves differently. The movement built a national infrastructure that advanced a racial critique of identity, economy, and culture, developed a body of knowledge around those of Asian and Pacific Islander descent in the United States and around the globe, and established a way of approaching questions of identity and justice.

As it did, Asian America became less than what its pioneers had hoped as well. Being Asian American now hardly requires radicality. In an era where pseudo-intellectuals like Michele Malkin can trade on their race and gender to decry feminist and antiracist work, it is no wonder that the hard-thinking, self-sacrificing renegades who made Asian Americans visible through their rigorous activism and art may now feel nostalgic for the old struggle.

But Asian America has always been about being in-between. Liminality is not permanent. Remember the old racist school rhyme about the Chinaman sitting on the fence? Racism always requires making a choice. But in the postmulticultural United States, racial hierarchy, our in-between positionas recipients of racist love almost as perilous as racist hateis at once comfortable and discomforting. Where do we go from here? The choices we make now will resonate long past the middle of this century, when the United States becomes a majority minority.

In this regard, the Long Sixties still casts its long shadow. Asian Americans may never find the same certitude the dreamers of then seemed to have about the path toward racial justice. At any rate, Ishizuka also shows the price of that certitude: the cruel self-policing, the horrible omissions, the paths left untaken. It is also true that each generation must deal with the struggles left unresolved by those who came before. While Ishizuka is committed to telling the story of her peers and her time, she is hardly a triumphalist. She is critical where the story demands it. These Asian American dreamers powerfully reshaped our world, but the failure of their revolutionand the subsequent compounding damage of five decades of reactionary backlashleaves us a half-century later with many of the conditions that shaped their eraresegregation, growing inequality, historical amnesia.

That is the nature of struggle. As Grace Lee Boggs, whose spirit lingers over Ishizukas book, reminds us, every change produces new conditions, new opportunities, and new battles. Our job is in part to recognize how we win just as precisely as we recognize how we lose, so that we may face the present and future without illusion. Ishizukas finally hopeful narrative lets us know that those who are concerned with change cannot submit to pessimism. History is not a burden, a blueprint, or an ending; it is a beacon. Serve the People may teach us how we might overcome our ache and learn to see and dream big again.

Discovery cannot be purely intellectual but must also involve action; nor can it be limited to mere activism, but must include serious reflection.

Paulo Freire

Up until the cultural revolution of the Long Sixtiesthe elongated decade that began in the mid 1950s and lasted until the mid 1970sthere were no Asian Americans. Rather, we were Americans of Japanese, Chinese, or Filipino ancestry: the ethnicities that constituted the majority of Asians in the United States at that time. Being non-white in a Eurocentric society, we were subject to the dominance of whiteness and subsequent subordination faced by all Americans of color. Yet not being black in a society that was defined and rendered in black and white rendered us inconsequential, if not invisible. And while we were Americansby 1970 almost 80 percent of Japanese Americans and roughly 50 percent of Chinese and Filipino Americans were born in the United Stateswe were not seen as such.