This edition published by Verso 2013, 1998

Translation and introduction R. I. Frank 2013

First English-language edition published by New Left Books 1976

First published as Agrarverhlnisse im Altertum, in Handwrterbuch der Staatswissenschaften, 1909; and Die sozialen Grnde des Untergangs der antiken

Kultur, in Die Wahrheit May 1896

Republished in Max Weber, Gesammelte Aufstze zur Sozial und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Tbingen 1924

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weber, Max, 18641920.

[Selections, English. 1988]

The agrarian sociology of ancient civilizations / Max Weber:

translated by R. I. Frank

p. cm.

First published as Agrarverhltnisse im Altertum, in Handwrterbuch der Staatswissenschaften, 1909; and Die sozialen Grnde des Untergangs der antiken Kultur, in Die Wahrheit, May 1896 T.p. verso.

Reprint. Originally published: London: NLB; Atlantic Highlands:

Humanities Press, 1976.

Contents: Translators introduction Economic theory and ancient society The

agrarian history of the major centres of ancient civilization The social causes of the

decline of ancient civilization.

Includes bibliographies.

eISBN: 978-1-78168-241-8

1. Economic history To 500. 2. Agriculture History. 3. Social Economic

condition. I. Title

HC31.W42213 1988

v3.1

Contents

Translators Introduction

In science, each of us knows that what he has accomplished will be antiquated in ten, twenty, fifty years. Analysis had till then largely held the field. Now, however, there is a renewed interest in theory and synthesis, and this work should at last gain the audience it deserves. Readers will find here a remarkable survey of 3,000 years, one which traces the institutional framework within which political and intellectual developments took place. They will find more if they know something about the author and his premises, methods, and purpose. What follows aims to give the essential information on these matters together with references for further study.

1. Author

Max Weber was born in 1864. His father was a wealthy lawyer and a leading member of the Imperial Parliament, so he grew up in Berlin and as a young man met many of the leading figures in German politics and scholarship. At the University of Berlin he studied law, writing his first dissertation on the mediaeval trading Thus Weber qualified himself in both German and Roman law, an unusual feat in those days and an early indication of his independence of traditional disciplinary boundaries.

The second dissertation is in many ways a key to Webers studies. It is based on complete mastery of the primary sources, in this case mainly a collection of abstruse Latin documents on surveying; here we see Webers link with the German school of legal historians who used philological methods to interpret legal sources and to trace the development of institutions. Weber in fact had close ties with the greatest member of this school, Theodor Mommsen, prince of philologists. At Webers first doctoral examination Mommsen questioned him closely on one of his theses, then concluded by saying that although still unconvinced he would offer no further objections. Younger men often have ideas which at first seem unacceptable But when the time comes for me to go, there is no one to whom I would rather entrust my work than the much esteemed Max Weber.

Now the historical school was characterized by Savignys famous argument against legal reform, and by his view of social change as organic, rooted in national character. Hence its members tended to ignore classes and conflicts of interest. Even Mommsens legal works show this trait, the more noteworthy since his personal views in politics were quite dissimilar.

But Webers 1891 work shows the influence of a very different approach. After registering his great debt to Mommsen he goes on to say that he had studied Roman agrarian institutions by first looking at their practical importance for particular interest groups, a method he had learned from his teacher, August Meitzen.

During the next few years this tendency to emphasize political factors grew more pronounced. Webers thinking centred on the struggle for power. He made this plain in the inaugural lecture he delivered in 1895 at Freiburg University on assuming the chair of economics: Even behind the processes of economic development we find the struggle for power, and when the nations power is at stake this immediately becomes the determining factor in shaping our economic policies. The study of economics is a political study, and it serves in the formation of policy not the policy of whatever class or clique holds power, but rather the policy which serves the permanent power interests of the nation.

Such statements have been interpreted as reflections of Webers oedipal hostility to his father and everything he stood for. This psychological explanation can be supported by a good deal of biographic data, and indeed the harshness of his views may have been connected with the severe inner conflicts he experienced during these years.

This aspect is crucial because it is a link with the two concerns which soon came to dominate Webers thought on politics and history, concerns which are of central importance in the present work: capitalism and rationalism.

The connection between capitalism and the modern bourgeoisie is well understood today by all. However in Imperial Germany the matter was more problematic because the issue between feudalism and industrialism had not yet been settled. The Junkers had gained a new lease of rule with Bismarck, and remained a dominant force until the fall of the monarchy. Because of Webers commitment to national power and his own political feelings he was necessarily strongly in favour of new leadership and new policies. Hence the great political struggles of the period forced him to think constantly of the relation between capitalism and his values as a member of the bourgeoisie and as a German.

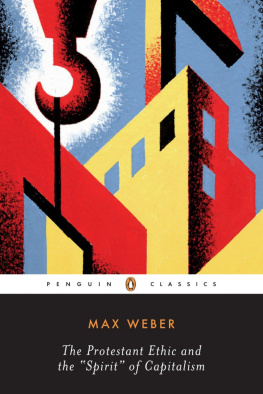

At this point, however, Weber added a highly personal contribution: he insisted on the intimate connection between bourgeoisie, capitalism, and rationalism. In 1904 he published the first part of his famous study on the relation between Calvinism and capitalism, one of the few great historical interpretations that have posed a problem where once was universal agreement or a void, in which he argued that the drive for profit had sprung from Puritan morality, the heir of monastic asceticism.

Here it is appropriate to note that this emphasis on rationalism began in 1904, just after Weber had recovered from a severe mental illness which afflicted him for six years. It seems a plausible inference that his struggle to regain sanity led him to centre his values about rationalism and also made him unusually sensitive to irrational tendencies in himself and his society.

This emphasis on rationalism helps us place Weber in the context of his times. The German academic community during 18901920 was divided sharply between supporters of traditionalism and modernity, and Weber became the leading modernist.