MASKS OF CONQUEST

GAURI VISWANATHAN

MASKS OF CONQUEST

Literary Study and British Rule in India

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, through a special grant, has assisted the Press in publishing this volume.

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2015 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53957-9

ISBN 978-0-231-17169-4 (pbk: alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-231-53957-9 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014942610

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

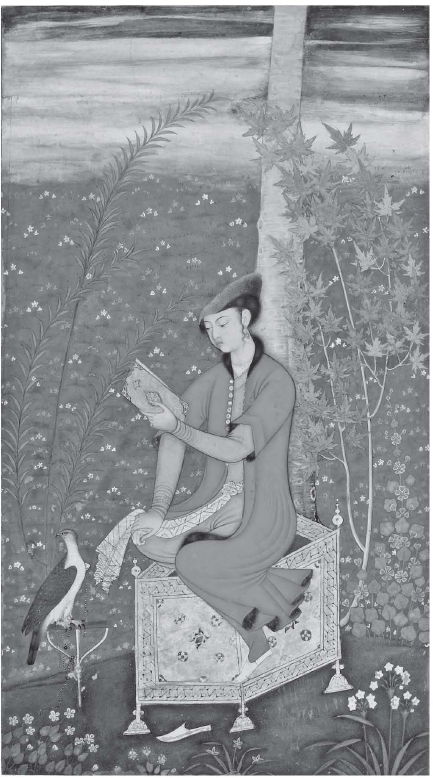

Cover image and frontispiece: Muhammad Ali, A Youth Reading, from the Nasiruddin Shah Album, c. 1610, reign of Jahangir, India. Opaque color, ink, and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase, F1953.93 Cover designer: Jordan Wannemacher

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

FOR MY PARENTS

Now we are to behold a literature so full of all qualities of loveliness and purity, such new regions of high thought and feeling that to the dwellers in past days it should have seemed rather the production of angels than of men.

Madras Christian Instructor and Missionary Record (1844), 2 (4): 195

We are not afraid of what we do see of British power, but of what we do not see.

Tipu Sultans minister, quoted in Parliamentary Papers, 185253, 29:42

Contents

THE CONTENT of English studies has changed so significantly in the last twenty-five years that it is almost embarrassing to revisit some of the assumptions that shaped my doctoral dissertation, which I subsequently revised as Masks of Conquest: Literary Study and British Rule in India. At that time, the studies available for engagement were largely triumphalist and insular, describing the rise of English studies exclusively from within the national boundaries of England. That, happily, is no longer the case. Perhaps the most significant effect of postcolonialismwith all its shortcomings, blind spots, and metropolitan evasionsis that the curricular study of English can no longer be studied innocently or inattentively to the deeper contexts of imperialism, transnationalism, and globalization in which the discipline first articulated its mission. It is no small matter that Caliban competes de rigueur with his creator Shakespeare as the canonical expression of present-day English studies. The archetypal figure of colonial subjugation and subversion underwrites a revisionist view of English studies as a composite of discordant voices, rather than the sweetness and light that Matthew Arnold envisaged as the ultimate triumph of English culture. Yet, as I shall argue here, even Caliban has marked his limits in driving English studies into a revisionist mode, as other forms of imaginative expression beyond reactive resistance are explored in the process of self-definition.

As a number of critics have noted, English studies is a relatively young discipline with barely a hundred and fifty years behind it. But despite its youth, its beginnings have always seemed somewhat opaque in the popular memory, as if English studies stretched back languidly to an origin identical with that of Englands. Genealogies that confine the discipline of English to England are belied by the transcontinental movements and derivations of the discipline. English has not one but multiple genealogies, which reveal that the disciplines origins are as diffuse as its current (and future) shape. There is a persistently shifting focus in the sites of cultural production and institutionalization, and distinctions between center and periphery dissolve, leaving huge question marks around the national attributes of literature. This leads one to question the appropriateness of even such commonly accepted designations as English studies or American studies. As Isabel Hofmeyr reminds us in The Portable Bunyan, John Bunyans The Pilgrims Progress became a canonical text in Britain only long after it had already circulated in Africa, initially for conversion purposes by Christian missionaries but subsequently as a reference point for African writers, who adapted Bunyans work to allegorize the condition of their own postcolonial societies. Not only did The Pilgrims Progress arrive late in the English curriculum, but it was also deuniversalized and remade as exclusively Englishthus no longer available for appropriation elsewhere. Interestingly, The Pilgrims Progress, in becoming wholly English, was further de-allegorized by being read as a geographically specific story set in southern England. The claims to universality overlapped with those of English humanism. The key revisionist understanding that emerges from Hofmeyrs study is that the international precedes the national, or to put it another way, the national is an aftereffect of the international.

The denationalizing of English or American studies raises an intriguing question about nomenclature. Particularly in decolonizing societies but no less relevant in the Anglo-American academy, it is worth asking whether in the foreseeable future English studies will become indistinguishable from world literature. Or will the now ubiquitous term global studies be the name by which English studies will henceforth be known? Lest we get overly excited about future prospects, we would do well to remind ourselves that, even as there are concerted attempts to engage in postnational reorganization of the discipline, English and American studies seem incapable of escaping the organizing rubric of nationhood. More often than not, one of the strongest challenges has come from postcolonial studies in its questioning of the sites of literary production as a necessary first step toward disentangling literary studies from nationality.

At the same time I am wary of claiming that any one field has greater instrumental power than another in denationalizing English or American studies. I think, for instance, of a volume like Postcolonial Moves: Medieval Through Modern, which is edited by two scholars of early modern Europe who use postcolonial theory as a tool, rather than as an end, to excavate the complexities of the premodern in order to reckon with the modernity that wrought colonialism. By refocusing attention on the linguistic, literary, and cultural hegemonies that establish the terms of colonial identity and difference, this volume succeeds in disrupting some of the national geographies and periodizations that generally structure disciplinary identifications. The broader implications have less to do with viewing earlier literary periods through the postcolonial lens, which can sometimes lead to reductive conclusions. Rather, this kind of scholarship questions the assumptions that locate colonialism, nationalism, and globalization squarely within the framework of modernity but refuse to acknowledge the extent to which the nonmodern or the premodern is implicated in such things as the formation of national categories. In some respects this backward glance at early modern Europe also broadens the European metropole to include the colonies, both moves paying due heed to the multiple sites and historical periods from which the idea of the nation is forged.