Table of Contents

ALSO BY STEPHEN J. PYNE

Voice and Vision: A Guide to Writing History and Other Serious Nonfiction (2009)

Awful Splendour: A Fire History of Canada (2007)

The Still-Burning Bush (2006)

Brittlebush Valley (2005)

Tending Fire: Coping with Americas Wildland Fires (2004)

Smokechasing (2003)

Fire: A Brief History (2001)

Year of the Fires (2001)

How the Canyon Became Grand (1998)

Vestal Fire: An Environmental History, Told Through Fire, of Europe and Europes Encounter with the World (1997)

Americas Fires: Management on Wildlands and Forests (1997)

World Fire: The Culture of Fire on Earth (1995)

Burning Bush: A Fire History of Australia (1992)

Fire on the Rim (1989)

The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica (1986)

Introduction to Wildland Fire (1984, 1996)

Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire (1982)

Grove Karl Gilbert (1980)

To Sonja

a polestar, as always

and Lydia, Molly, Karlie, Ashley, Lindsey, Colten, Julie, and Ivy

a new constellation in the heavens

An age will come after many years when the Ocean will loose the chains of things, and a huge land lie revealed; when Tethys will disclose new worlds and Thule no more be the ultimate.

Seneca,Medea(ca. AD 40)

Throw back the portals which have been closed since the worlds beginning at the dawn of time. There yet remain for you new lands, ample realms, unknown peoples; they wait yet, I say, to be discovered.

Richard Hakluyt,The Principal Navigations,

Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the EnglishNation(1587)

Come, my friends, Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Alfred Tennyson, Ulysses (1842)

There are no more unknown lands; the new frontiers for adventure are the ocean floors and limitless space.

J. Tuzo Wilson,I.G.Y.: The Year of the New Moons(1961)

Mission Statement: Voyager of Discovery

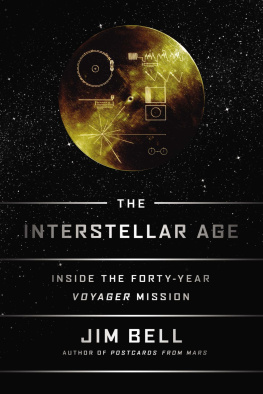

On August 20 and September 5, 1977, two spacecraft, Voyager 2 and Voyager 1, respectively, lifted off atop Titan/ Centaur rockets from Cape Canaveral, Florida, to begin a Grand Tour of the outer planets. Some 33 years and 21 billion kilometers later, having surveyed Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, their moons, and the interplanetary medium, and sent back enough digital information to fill a Library of Congress, they find themselves within the diaphanous heliosheath that divides the Sun from the stars. They have sufficient power for another ten years of operation, and racing at 440 million kilometers a year, that should grant them enough stamina to sail beyond the reach of the solar gases altogether and enter the interstellar winds before they expire.

The Voyager mission culminated what many of its contemporaries have come to regard as a golden age of American planetary exploration and what the future may well identify as the grand gesture of a Third Great Age of Discovery, the most recent revival of geographic journeying and questing in a chronicle that, for Western civilization, traces back to the fifteenth century. Yet what it has done for geography, the Voyager mission also does for history: the saga of the Voyagers trek is carrying the inherited narrative of exploration to its outer limits, and perhaps beyond.

The countdown for the Grand Tour began twenty years earlier when, within the context of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), the Soviet Union lofted Sputnik 1 into orbit on October 4, 1957. The feat caused a sensation. Orbiting every ninety minutes, it sent out a beep that broadcast both triumph and taunt. The United States failed in its counter-launch of Vanguard 1 before succeeding with Explorer 1, on January 31, 1958. Thereafter, the two rival superpowers of the cold war began a long volley of launches that extended their geopolitical rivalry beyond the confines of scientific competition and the gravitational reach of Earth, and that, whether they intended the outcome or not, helped birth a new epoch of geographic exploration. Modern rockets had breached an ancient barrier to beyond.

From 1962 to 1978 America launched a flotilla of spacecraftPioneer, Mariner, Viking, and Voyagerto orbit the inner planets and survey the outer ones. In an outburst comparable to that of the sixteenth-century Portuguese marinheiros into and across the Indian Ocean or the eruption of eighteenth-century circumnavigators into the Pacific, American spacecraft would visit all the major bodies of the solar system save Pluto. But even as Voyager was wending through the asteroid belt, the institutional apparatus that launched it was collapsing. Less than a year after Voyager 1 launched, the Pioneer Venus Orbiter fired off, and then, for eleven years, no other American spacecraft trekked beyond the bonds of Earth. Throughout those years the Voyagers defined the American planetary program.

For some participants, those years bracket the acme of American space exploration. For others, the borders of a golden age are more elastic, reaching back to Explorer 1 or even to the lonely experiments of Robert Goddard and extending onward to the recent journey of Cassini to Saturn and the brave sojourn of New Horizons to extraplanetary Pluto and the Kuiper Belt. Others scorn so American an emphasis and insist that the circle include such visionaries as Hermann Oberth and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the relentless outpouring of Soviet spacecraft, the proliferating efforts of the European Space Agency, and the satellites of Japan, India, and China, all of which expand the scope of the undertaking. For a few observersthe most visionary or fancifulthe epic begins in evolutionary mists, when marine life first crawled onto land, or when early Homo of an unquenchable curiosity acquired fire; and for such prophets, the tale can end only when humanity, perhaps genetically self-engineered beyond recognition, wanders outside the solar system altogether.

But all seem to agree that what lifted off from launchpads at Tyuratam and Cape Canaveral was something both novel and inevitable, and that it portended a fabulous new era of discovery, a journey beyond anything humanity had known before. In the past, geopolitics had repeatedly projected rivalries internal to Europe outward onto a wider world. With the launches of Sputnik and Explorer the cold war prepared to do the same, and this time the competition would transcend Earth itself. It would reach beyond sordid politics and the blinkered ambitions of its originating time and place. Those who meditated on the launches believed they were witnessing a transit of history that would define the dimensions of human time, like the transit of a planet across the Sun that demarked the dimensions of space. They did not know what lay beyond, or how they might reach it, only that they were determined to go.

After the launch of Explorer 1 in 1958, a press conference led to one of the canonical images of the ensuing space age, as three menWernher von Braun, James Van Allen, and William Pickeringhefted a mock-up of Explorer 1 over their heads. That tableau made visible the competition that drove the launches, a cold war that refused to be bound by Earth and carried its geopolitical jousting into space. But there, too, in the personality of each man and the cultural ambitions he represented, were the internal rivalries, both institutional and intellectual, behind the launch. Each man stood for a competing vision of what space might represent.