Copyright 1978 by Carl Sagan

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada, Limited, Toronto, Canada.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Main entry under title:

Murmurs of earth.

Reprint of the ed. published by Random House, New York.

Includes index.

CONTENTS: Sagan, C. For future times and beings.Drake, F. D. The foundations of the Voyager record.Lomberg, J. Pictures of earth.Sagan, L. S. A Voyagers greetings.Druyan, A. The sounds of earth.Ferris, T. Voyagers music.Sagan, C. The Voyager mission to the outer solar system.Sagan, C. Epilogue.

1. Project VoyagerAddresses, essays, lectures. I. Sagan, Carl, 1934

[TL789.8.U6V685 1979] 001.550999 79-15209

eBook ISBN: 978-0-307-80202-6

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-0-679-74444-3

This edition published in hardcover by Random House, Inc.

First Ballantine Books Edition: November 1979

v3.1

To the makers of musicall worlds, all times

The Contents of the Voyager Record

118 pictures

The first two bars of the Beethoven Cavatina

Greetings from the President of the United States

Congressional List

Greetings from the Secretary General of the United Nations

Greetings in fifty-four languages

UN Greetings

Whale Greetings

The Sounds of Earth

Music

Contents

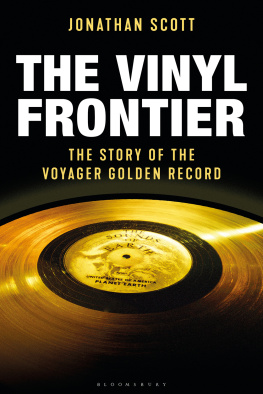

On August 20th and September 5th, 1977, two extraordinary spacecraft called Voyager were launched to the stars. After what promises to be a detailed and thoroughly dramatic exploration of the outer solar system from Jupiter to Uranus between 1979 and 1986, these space vehicles will slowly leave the solar systemsemissaries of Earth to the realm of the stars. Affixed to each Voyager craft is a gold-coated copper phonograph record as a message to possible extraterrestrial civilizations that might encounter the spacecraft in some distant space and time. Each record contains 118 photographs of our planet, ourselves and our civilization; almost 90 minutes of the worlds greatest music; an evolutionary audio essay on The Sounds of Earth; and greetings in almost sixty human languages (and one whale language), including salutations from the President of the United States and the Secretary General of the United Nations. This book is an account, written by those chiefly responsible for the contents of the Voyager Record, of why we did it, how we selected the repertoire, and precisely what the record contains.

Carl Sagan

F. D. Drake

Ann Druyan

Timothy Ferris

Jon Lomberg

Linda Salzman Sagan

February 1978

I had monuments made of bronze, lapis lazuli, alabaster and white limestone and inscriptions of baked clay I deposited them in the foundations and left them for future times,

Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, seventh century B.C.

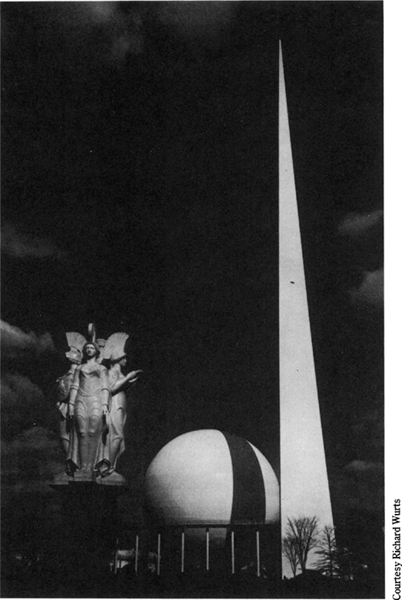

The Trylon (right) and Perisphere (center) of the 1939 New York Worlds Fair. The statuary at left represents Four Victories of Peace, by John Gregory.

In 1939, before my fifth birthday, my parents took me to the New York Worlds Fair. It exhibited wonders. Lightning was made to crackle, blue and fearsome, between two metal spheres. A sign read Hear light! See sound! and it turned out that, sure enough, such things were possible. There were buildings devoted to strange cultures and faraway lands of whose very existence I had been totally ignorant. The centerpiece of that Worlds Fair was the Trylon and Perisphere, a stately, tapering tower and a building-sized sphere in which was something called The World of Tomorrow. You walked on a high-railed ramp and below you, in miniature, was an exquisitely detailed model of the futuregraceful aerial skyways filled with streamlined automobiles and happy citizens purposefully intent on some futuristic business, the nature of which was difficult to divine from the perspective of my limited experience and abbreviated stature. But one message was clearly communicated: there were other cultures and there would be future times.

The confidence in the future evinced by that Worlds Fair was dramatically illustrated by the Time Capsule, a chamber hermetically sealed, filled with newspapers, books and artifacts of 1939, buried in Flushing Meadows to be opened and revealed automatically in some distant epoch. Why? Because the future would be different from the present. Because those in the future would want to know about our time, as we are curious about our antecedents. Because there was something graceful and very human in the gesture, hands across the centuries, an embrace of our descendants and our posterity.

There have been many time capsules both before and since. Esarhaddon, son of Sennacherib, was a mighty general and an able administrator, but he also had a conscious interest in presenting not just his military glory but his entire civilization to the future, burying cuneiform inscriptions in the foundation stones of monuments and other buildings. Esarhaddon was king of Assyria, Babylonia and Egypt. His military campaigns extended from the mountains of Armenia to the deserts of Arabia. For all that, his name is hardly a household word today, but his works have made a significant contribution to our knowledge of the Middle East in the seventh century B.C. His son and successor, Assurbanipal, perhaps influenced by the time-capsule tradition of his father, accumulated a massive library on stone tablets comprising the knowledge of all that was known in that remote epoch. The remains of Assurbanipals library are a remarkable resource for scholars of today. Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal have spoken clearly down through the centuries and millennia. For those who have done something they consider worthwhile, communication to the future is an almost irresistible temptation, and it has been attempted in virtually every human culture. In the best of cases, it is an optimistic and far-seeing act; it expresses great hope about the future; it time-binds the human community; it gives us a perspective on the significance of our own actions at this moment in the long historical journey of our species.

The coming of the space age has brought with it an interest in communication over time intervals far longer than any Esarhaddon could have imagined, as well as the means to send messages to the distant future. We have gradually realized that we humans are only a few million years old on a planet a thousand times older. Our modern technical civilization is one ten-thousandth as old as mankind. What we know well has lasted no longer than the blink of an eyelash in the enterprise of cosmic time. Our epoch is not the first or the best. Events are occurring at a breathless pace and no one knows what tomorrow will bringwhether our present civilization will survive the perils that face us and be transformed, or whether in the next century or two we will destroy our technological society. But in either case it will not be the end of the human species.