Software Studies

Matthew Fuller, Lev Manovich, and Noah Wardrip-Fruin, editors

Expressive Processing: Digital Fictions, Computer Games, and Software Studies, Noah Wardrip-Fruin, 2009

Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life, Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge, 2011

Programmed Visions: Software and Memory, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, 2011

Speaking Code: Coding as Aesthetic and Political Expression, Geoff Cox and Alex McClean, 2012

10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1));: GOTO 10, Nick Montfort, Patsy Baudoin, John Bell, Ian Bogost, Jeremy Douglass, Mark Marino, Michael Mateas, Casey Reas, Mark Sample, and Noah Vawter, 2012

The Imaginary App, Paul D. Miller and Svitlana Matviyenko, 2014

The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, Benjamin H. Bratton, 2015

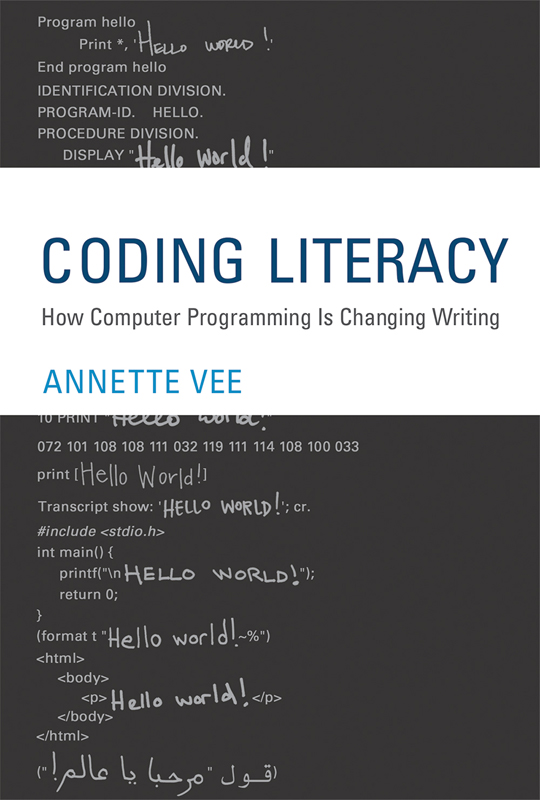

Coding Literacy: How Computer Programming Is Changing Writing, Annette Vee, 2017

Coding Literacy

How Computer Programming Is Changing Writing

Annette Vee

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in ITC Stone Serif Std by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-0-262-03624-5

eISBN 9780262340229

ePub Version 1.0

Series Foreword

Software is deeply woven into contemporary lifeeconomically, culturally, creatively, politicallyin manners both obvious and nearly invisible. Yet while much is written about how software is used, and the activities that it supports and shapes, thinking about software itself has remained largely technical for much of its history. Increasingly, however, artists, scientists, engineers, hackers, designers, and scholars in the humanities and social sciences are finding that for the questions they face, and the things they need to build, an expanded understanding of software is necessary. For such understanding they can call upon a strand of texts in the history of computing and new media, they can take part in the rich implicit culture of software, and they also can take part in the development of an emerging, fundamentally transdisciplinary, computational literacy. These provide the foundation for Software Studies.

Software Studies uses and develops cultural, theoretical, and practice-oriented approaches to make critical, historical, and experimental accounts of (and interventions via) the objects and processes of software. The field engages and contributes to the research of computer scientists, the work of software designers and engineers, and the creations of software artists. It tracks how software is substantially integrated into the processes of contemporary culture and society, reformulating processes, ideas, institutions, and cultural objects around their closeness to algorithmic and formal description and action. Software Studies proposes histories of computational cultures and works with the intellectual resources of computing to develop reflexive thinking about its entanglements and possibilities. It does this both in the scholarly modes of the humanities and social sciences and in the software creation/research modes of computer science, the arts, and design.

The Software Studies book series, published by the MIT Press, aims to publish the best new work in a critical and experimental field that is at once culturally and technically literate, reflecting the reality of todays software culture.

Acknowledgments

Like all monographs, this book wasnt a solo project. Ive been helped by many people and material grants during the decade in which it has taken shape. The book came out of my dissertation, which was guided expertly by Deborah Brandt at the University of WisconsinMadison. Through her care, humor, gentle but spot-on critique, and infallible support, Deb has been a model researcher, teacher, writer, and person to me (among many others). When considering any professional decision, I often ask myself: What would Deb do? And then I know the way. I learned about 90% of what I know about teaching writing from the University of WisconsinMadison Writing Center and Brad Hughes, who brings intellectual rigor and careful research to administration and teaching and has a superhuman ability to juggle a hundred commitments and thousands of students while making everyone around him feel smart and capable. David Fleming helped to show me I was in the right field and doing good work. Kurt Squire and Greg Downey introduced me to sources beyond my own field and treated me like a colleague even when I was a grad student. Mike Bernard-Donals bore with me, an outsider, in my first graduate class and saw me all the way through my dissertation defense. His helpful skepticism strengthened my work; when he said it was ready, I knew that it finally was.

My fellow students at Wisconsin were also essential to the substance and style of this work, in particular, Kate Vieira, Tim Laquintano, Scot Barnett, Rik Hunter, and Adam Koehler. Tim, Rik, Scot, and I worked together to learn digital literacy scholarship and technologies. Kate has been a great friend and guiding star for me since 2004; without her, I might not have entered the field of composition or finished my dissertation, and I certainly would have had a duller and dimmer graduate school experience. Corey Mead, Alice Robison (Daer), Stephanie Kerschbaum, Mira Shimabukuro, Eric Pritchard, Maria Bibbs, Chrissy Stephenson, and Mike Shapiro were all excellent fellow-travelers. Kate and Tim read countless early drafts of this book and my other work. They are everywhere in it. Mike Shapiros tough love on a full draft of the book helped me clarify ideas and language. I wish that all grad students had a peer group such as I enjoyed at Wisconsin.

Ive been lucky to have brilliant and generous colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh as well. Ryan McDermott helped me find additional sources and vet my claims about medieval literacy. Steve Carr offered useful comments on an article version of this book. Jean Ferguson Carr has been a generous, encouraging, and savvy mentor to me, clearing the way for the book to get done. Johnny Twyning and Don Bialostosky have been supportive chairs of my department and have gone over and above to boost me up. Alison Langmead has been a stunning collaborator and Ive learned at least as much from her as our students have. Pitt graduate students are the best: Ive been lucky to run seminars brimming with their creative ideas. I owe particular thanks to Kerry Banazek, who is not only a strong and brilliant human, and willing to take a chance on me as an advisor, but who also helped me to proofread this book. Lauren Rae Hall and Lauren Campbell, Ive cited you both here, but I cant cite everything Ive learned from you. Ive benefitted from research leave at Pitt, and even more importantly, maternity leave for the birth of my two children. A heartfelt thanks to the administrators and other women who paved the way for me to enjoy the privilege of being with my babies while not sidelining my research or career, especially Jean Ferguson Carr, Phil Smith, and Jim Knapp. I wish that all parents, especially mothers, had this right.

Composition and rhetoric, what I consider my home field, is a lovely place to be. It includes people like Jim Brown, who has been a good friend and collaborator; Doug Eyman, who has been a guide in digital rhetoric and publishing and a helpful, humorous mentor; Cheryl Ball, who does it all; Gail Hawisher and Cindy Selfe, who paved the way; Brian Ballantine, Alanna Frost, and Suzanne Blum Malley, who make conferences way more fun; Christina Haas and Elizabeth Losh, who have both offered smart and critical comments on my work; Alexandria Lockett, who brilliantly calls it like it is and inspires me to do better; Chris Lindgren, who has put ideas about coding and literacy into practice and put me in contact with great people and many more besides. Thanks for making comp/rhet feel like home.

Next page