Editor: Charlotte Greenbaum

Designer: Max Temescu

Managing Editor: Annalea Manalili

Production Manager: Alison Gervais

Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for

and may be obtained from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-4197-3998-9

eISBN 978-1-68335-733-9

Text copyright 2020 Tommy Jenkins

Illustrations copyright 2020 Kati Lacker

Font copyright 2020 Kati Lacker

Foreword 2020 Martha S. Jones

Published in 2020 by Abrams ComicArts, an imprint of ABRAMS.

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical,

electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written

permission from the publisher.

Abrams ComicArts books are available at special discounts when

purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising

or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification.

For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams ComicArts

is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

v

Foreword

The right to vote has grown out of struggle. Our national history is littered with

scenes in which getting to the polls involved far more than a simple buggy or bus ride

across town. Casting a ballot has rarely been as easy as showing up and dropping a

paper slip in a box or pulling a lever. Each Election Day, for nearly two and a half cen-

turies, Americans have acted as the People and chosen their elected representatives.

Their votes are the products of campaigns, battles, court challenges, and the risking

of livesall so that the best promises of democracy can be tested and, as President

Barack Obama often quoted from the Constitution, come closer to realizing a more

perfect union.

I begin each Election Day with a personal get-out-the-vote campaign. My follow-

ers on social media know that early on the first Tuesday in November, my feed will fill

with images intended to inspire us to get to the polls. They include the Constitutions

3/5ths Compromise, which reduced enslaved Americans to a figure that undercut their

humanity while increasing the power of those states that allowed for human bondage.

There is an engraving from 1867,

The First Vote , that depicts a trio of black men casting

their ballots in the wake of the Civil War and the constitutional revolution that abolished

slavery, guaranteed citizenship, and promised black men voting rights. I always include

a photograph of those who marched out of Selma, Alabama, and across the Edmund

Pettus Bridge in 1965, before passage of the Voting Rights Act later that year, demand-

ing access to the polls. Their courage was met by the raw brutality of clubs and kicks.

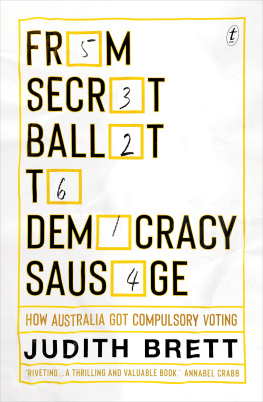

Drawing the Vote

reminds us that every time an American citizen votes, they are

taking part in the long struggle for voting rights.

If that story began as the framers of the Constitution debated how to share power

in the new United States, it continues today in battles over voter identification, gerry-

mandering, foreign interference, and the closing of polling places. Americans still do not

agree on how to ensure the right to vote, and

Drawing the Vote

explains how we got

here. While, for example, access to the polls expanded for white men in the early part of

the nineteenth century, it closed for black menthe descendants of enslaved people

who saw their ballots taken away in states like New York and Pennsylvania. Immigrant

men were entering the body politic only by giving up their allegiances to their home-

landsthe price they paid for becoming part of what was still a white mans republic. At

the same moment, American womenblack and whitebegan to demand their right to

vote. Still, most would wait until the twentieth century to freely cast their ballots. In our

own time, after Election Days wind down, the focus is often on winners versus losers. But

behind the results are the stories of how every generation of Americans has struggled to

influence the outcomes.

Like the family of

Drawing the Vote

author Tommy Jenkins, my people come from

North Carolinablack residents of the city of Greensboro, where their right to vote was

denied for much of the states history. My earliest forebearslike Elijah Jones, born in

1802may have voted because only in 1835 did free persons of color like him lose

the right to vote. That year the state limited the ballot to white men, though even

they, too, struggled against a property qualification that was not lifted until 1856. Still,

the color line kept African Americans from the polls. After the Civil War, men like my

great-great-grandfather Sidney Dallas Jones, born in 1845, voted for the first time. He

went on to become a Republican Party activist and, in 1868, helped elect the states

first African American legislators. But by 1904, the political aspirations of Sidneys sons,