Warrior Robert - The World of Indigenous North America

Here you can read online Warrior Robert - The World of Indigenous North America full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Taylor & Francis Group, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The World of Indigenous North America

- Author:

- Publisher:Taylor & Francis Group

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The World of Indigenous North America: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The World of Indigenous North America" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The World of Indigenous North America — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The World of Indigenous North America" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Courts, Police, and the Law

Carole Goldberg and Duane Champagne

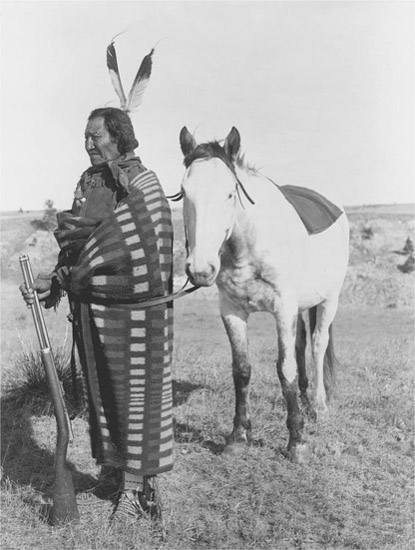

Crow Dog, his rifle and horse.

Case 1, Crow Dogs Case at Rosebud . No one knows for certain why one Lakota Chief, Crow Dog, killed another Chief, Sinte Gleska (or Spotted Tail), on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota that summer of 1881. Some say it was conflict over the proper response to heavy-handed federal officials; others, that it was contention over a woman. What is not in doubt, however, is that the families involvedresolved the matter to their satisfaction under Lakota law. There was an apology and an exchange of money, horses, and blankets to Sinte Gleskas kin as compensation for their lost relative, according to traditional Lakota concepts of restorative justice. Several years later, disgruntled United States officials tried to prosecute Crow Dog for murder. Although Crow Dog was convicted, the United States Supreme Court set him free, pointing out that the federal law existing at that time gave no authority to the federal courts to hear an on-reservation criminal case where both offender and victim were Indian. Only the tribes had jurisdiction to address such matters. Congress quickly filled in that gap with passage of the Major Crimes Act, a law that, for the first time, made it a federal offense for one Indian to commit a serious crime against another within Indian territory.

Case 2, Double Prosecution for a Navajo. Nearly one hundred years later, in 1974, a Navajo man was picked up by Navajo tribal police on a high school located on the Arizona portion of the Navajo Reservation. Brought before a Navajo tribal judge, he was charged with disorderly conduct in violation of the Navajo Tribal Code. Two days after the arrest, the defendant pleaded guilty in tribal court to that charge and to a further charge of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, also a tribal member. His sentence was 60 days in tribal jail or a fine of $150. Not too long thereafter, the same defendant was charged and convicted in federal court for the same events, only this time the prosecution was for statutory rape. When his case came up to the United States Supreme Court, the Court upheld the federal conviction, even over the defendants complaints of double jeopardy. The Navajo Nation and the United States are separate sovereigns, the Court said, and therefore double jeopardy doesnt apply. Both the tribal conviction and the federal conviction could stand.

Case 3, Healing-to-Wellness at Tulalip . Thirty years after that, in 2005, a member of the Tulalip Tribes in Washington state stood before a tribal court, charged with possession of drugs on the reservation. The court was called a healing-to-wellness court, and it provided an alternative to criminal prosecution. Its aim was to help low-level offenders with drug or alcohol problems return to a healthy, productive role in their communities. Defendants before this special court had to undergo regular drug tests, attend regular meetings with the judge and group meetings with other participating defendants, participate in ceremonies and instruction with tribal elders, and reside in a clean and sober household. Tribal social services agencies were enlisted to help them with child welfare, housing, employment, and other issues. The defendant was told that if she failed a drug test or failed to abide by these conditions, she could be sent to jail. At the time, she was living with the babys father, a young man who used drugs but had not been charged. To enable her to continue in the healing-to-wellness program, the father volunteered himself into the program, opening himself to the possibility of jail time if he failed a drug test. Eventually the defendant completed the program successfully, and delivered a healthy baby. No federal or state court got involved. A few years earlier, Washington state courts would have been the only courts available to hear the drug charges against this woman, due to a special law that Congress passed in the 1950s, known as Public Law 280. But Tulalip had long complained that the local police and courts didnt really care what happened on the reservation; and in 2000, the Tulalip Tribes convinced Washington to give up most of its criminal jurisdiction, leaving the Tribes in charge of less serious offenses.

Judge Gary Bass and Judge Theresa Pouley of the Tulalip Tribal Court. Harvard Project Honoring Nations 2006 award: AlterNative Sentencing Program, Tulalip Tribal Court. Photo by John Rae NYC.

Case 4, Stopping Meth Dealers at Wind River . On the 2.2-million acre Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, home to the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes, one of the legacies of federal rules forcing tribal children into boarding schools is intergenerational trauma and associated alcohol addiction. Early in the twenty-first century, methamphetamine dealers from Mexico saw an opportunity in that affliction. They also became aware that federal court decisions made it impossible for tribes to prosecute non-Indians, and federal officials cared little about routine, on-reservation crimes. So these meth dealers targeted tribal members to become users and distributors, establishing networks among certain families. Violent crime skyrocketed. Finally, a task force of tribal, federal, and state officials intervened, arresting outsiders and tribal members involved in the ring. Federal courts imposed stiff sentences on those convicted, including life sentences on the masterminds from outside the reservation.

Though these cases involve four of the hundreds of Indigenous groups in North America, they capture dominant themes of courts, police, and law in Indian country: the contrast between longstanding Indigenous justice practices and Anglo-American understandings of justice; the development of new institutions of Indigenous justice in response to new conditions; the complexities of jurisdiction over reservation-based matters; and the tensions and difficulties that can arise when external authorities assert their power over Indigenous communities.

Mike Shockley, an officer with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, on patrol on the Wind River Indian Reservation near Fort Washakie, Wyoming, June 19, 2010. Robert Durell.

Contemporary courts, police, and law for Indigenous nations in Canada and the United States are bound not only to the legal and organizational frameworks of the non-tribal government, but also are informed by the continuity of tribal cultural understandings of justice and law. For reservation communities in the United States, the administration of justice is multi-cultural, multi-institutional, and multi-jurisdictional. Courts, policing, and the law in Canada and Mexico are dominated by the institutions of the nation-state. Indigenous peoples are legally obligated to participate in the law, courts, and policing arrangements that are the same as other nation-state citizens. In recent decades, tribal communities in Canada and Mexico have been seeking to reestablish local Indigenous community ways of managing justice. In the United States, since the 1960s, reservation communities have sought to increase tribal autonomy and sovereignty by assuming greater management of courts, creating tribal police departments, establishing tribal laws, and incorporating tribally specific justice concepts and processes. Indigenous peoples want to maintain orderly and just communities, but they want to do so in ways that are informed by and express their own cultures and institutions of justice.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The World of Indigenous North America»

Look at similar books to The World of Indigenous North America. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The World of Indigenous North America and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.