Jeffers Lennox - North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution

Here you can read online Jeffers Lennox - North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Yale University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution

- Author:

- Publisher:Yale University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jeffers Lennox: author's other books

Who wrote North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

NORTH OF AMERICA

Contents

NORTH OF AMERICA

Prologue

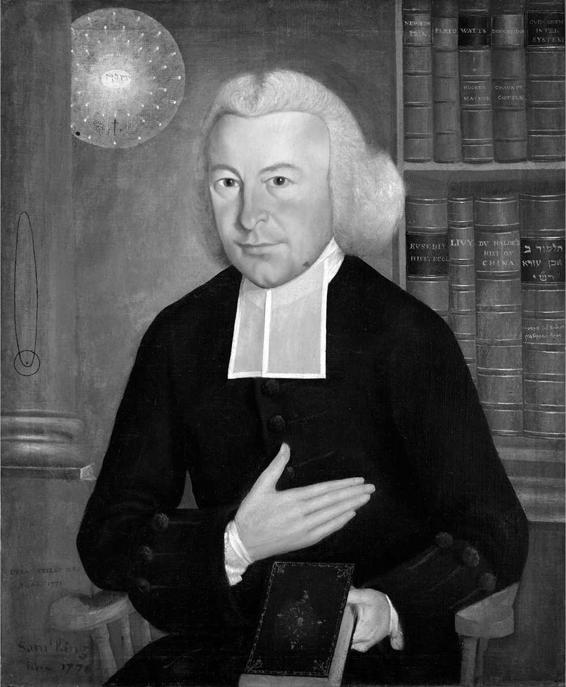

W HEN EZRA STILES FIRST learned of the Quebec Act, he recorded his sentiments in a diary. It was 23 August 1774, and he was upset. The King has signed the Quebec Act, he wrote, extending that Province to the Ohio & Mississippi and comprehending nearly two thirds of the territory of English America, and establishing the Romish Church & idolatry over all that space. He was astonished that leading imperial figures should expressly establish Popery over three Quarters of their Empire. The act was intolerable not simply because Catholics could continue practicing their religion in Quebecan accommodation provided by the Royal Proclamation of 1763but because Quebecs territory now extended down the back of the American colonies.

While often listed among the other intolerable acts imposed on the American colonies after the Boston Tea Party, the Quebec Act (often called the Canada Bill) was a unique piece of legislation. It did not spring fully formed from Parliament in the summer of 1774 but was years in the making and relied on established precedent for dealing with foreign subjects. In many ways it was the culmination of a string of proclamations and treaties dating from the fall of Quebec in 1763 at the end of the Seven Years War, when France ceded its North American colonies to Great Britain. But its history went deeper than the capture of New France. British administrators had struggled to govern French subjects and their Indigenous allies since 1713, when French Acadia fell under de jure British control and was renamed Nova Scotia.

When Quebec fell to the British in 1763, the British reduced its size. French Quebec had extended into the Ohio River Valley, but British Quebec

The Proclamation of 1763 was meant to regulate the governance of French and Indigenous territories, but it was an expedient measure that failed to recognize the realities on the ground. It created a border between British and Indigenous territory along the Appalachian Mountains, which separated water flowing into the Atlantic from that running toward the Mississippi. But in doing so, it ignored the regions west of the boundary where British settlers already resided and lands east of the boundary under Indigenous control. It was left to the superintendents for Indian AffairsSir William Johnson in the northern department and John Stuart in the southernto craft acceptable boundaries between British and Indigenous lands.

William Johnson was born in Smithtown, County Meath, Ireland, around 1715 and came to British America in 1738 to oversee his uncles estate in the Mohawk Valley. Success in trade and good relations with the powerful Iroquois Confederacy quickly paved the road for official positions. Appointed superintendent for Indian Affairs for the northern department in 1756, he had a talent for using Indigenous ways for his own profit. According to one (likely apocryphal) story, Johnson was in a

As land speculators pressured the British government to open the west, and Indigenous nations witnessed violence and enclosures on their traditional lands, Johnson worked to secure more realistic boundaries between colonies and homelands. At the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768), he negotiated a boundary four hundred miles farther west than the Proclamation line while also protecting Indigenous claims to the Ohio Valley.

Johnsons ability to win Indigenous support while retaining the imperial administrators trust secured his position, and he soon employed several deputies to assist him and keep him informed of regional issues. Johnson and his agents often faced the complicated task of also governing French settlers, who had established trading posts and settlements on Indigenous lands throughout the eighteenth century. From the imperial perspective, then, reserving territory for Indigenous peoples also prevented the extension of British law to the French inhabitants south of the Great Lakes. In considering a new plan for governing the French subjects in Quebec, officials had to keep in mind French subjects living in the heart of the continent. After 1763, Johnson (who died unexpectedly in 1774), his deputies, and his nephew (who replaced him as superintendent) helped triangulate British-Indigenous-French relations in lands Britain claimed but could not control.

The Indigenous nations who worked to assert control over their territory did not forget the promises made in the 1760s. It fell to Daniel Claus, one of Johnsons deputies, to answer Indigenous concerns in Canada. The Hurons had moved from the Great Lakes to a region controlled by the French. The British now controlled that region, so new rules applied. That both the French and the British had settled on Indigenous land, with its own established laws and customs, appears never to have crossed Clauss mind.

In 1773, Lord Dartmouth, the secretary of state for the colonies, wrote to Thophile-Hector de Cramah, the lieutenant governor of Quebec, and outlined his concerns for governing Quebec, particularly as they related to the provinces boundary. The Limits of the Colony will also in my Judgement make a necessary part of this very extensive Consideration, he wrote, adding, There is no longer any Hope of perfecting that plan of Policy in respect to the interior Country, which was in Contemplation when the Proclamation of 1763 was issued. He was more concerned about the Canadians who were promised their religion than about the Indigenous nations whose homelands were officially protected by the Royal Proclamation and later treaties.

In the decade after 1763, leading colonial officials, such as the governor of Quebec, Guy Carleton (later Lord Dorchester), and imperial bodies, including the Board of Trade and Privy Council, discussed, drafted, and redrafted what would eventually become the Quebec Act. Carleton believed that Quebec would be best governed if British officials agreed to restore the colonys pre-1763 boundaries, extending it into the Ohio Valley. Other government figures, including Wills Hill (Lord Hillsborough, the secretary of state for the colonies) and Francis Maseres (Quebecs attorney general) refused to relinquish the idea that Quebec would become a Protestant province, but Carleton believed loyalty would be best preserved if the Canadians could maintain their religion. To that end, he suggested to Hillsborough in 1768 that a coadjutor be appointed to guarantee the continued presence of a bishop in the province and thus fend off troublesome complaints from Rome. While Hillsborough disagreed, Carleton ignored him and, in 1770, named Canadian priest Louis-Philippe Mariauchau dEsgly to the position.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution»

Look at similar books to North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.