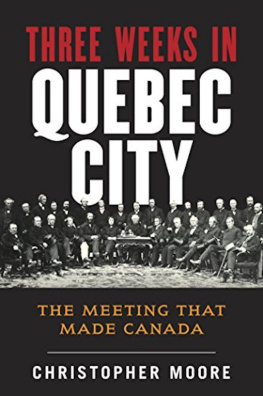

Copyright 1984 by Christopher Moore

Additions to original edition:

Copyright 1994 by Christopher Moore Editorial Ltd.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Canadian Reprography Collective is an infringement of the copyright law.

First published in hardcover by Macmillan of Canada in 1984.

First published in paperback by McClelland & Stewart in 1994.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Moore, Christopher

The Loyalists: revolution, exile, settlement

eISBN: 978-1-55199-484-0

1. United Empire Loyalists. 2. United States History Revolution, 1775-1783. 3. Canada History 1763-1867. I. Title.

FC426.M66 1994 971.024 C94-930040-3

E277.M76 1994

McClelland & Stewart Inc.

The Canadian Publishers

75 Sherbourne Street,

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

v3.1

Contents

Preface

The Loyalists Themselves

FOR TWO HUNDRED YEARS THE LOYALISTS HAVE BEEN turning into bronze. Statues and plaques stand in half the cities and towns of eastern Canada to affirm their contribution to the country, but we seem to resist letting the loyalists be anything but statues and plaques. Hardly sure who they were or what they did, we have remembered them as ancestors, but even more as symbols and abstractions of monarchy, of empire, of tradition, of tory power. Honoured or shunned according to current enthusiasms, they are rarely considered for their own flesh-and-blood concerns.

Perhaps this is natural, for it is easy to reduce history to politics and historical characters to labels. But the loyalists themselves have also seemed to resist a more personal attention. As many historians have observed, pioneers rarely enjoyed the luxury of documenting themselves extensively, and so in places the historical record has been thin. More important, perhaps, when they did leave record of themselves, the loyalists did not always say what we might want them to say. Frequently they When we push beyond the surface of most eighteenth century sources and ask questions about the character of individuals lives, says American historian Pauline Maier, we are often asking what our subjects had no intention of telling us.

To bridge that gap and to approach the personal experience of the loyalists, I have attempted to place them in the American societies that shaped them and the Canadian ones to which they came and contributed. Instead of following loyalist traditions into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I have tried to present careers and voices that do manage to speak to us from the loyalists themselves, whether in a Scottish-American soldiers pungent letters or in the private diary of a peaceable Massachusetts merchant. Even if the loyalist in question did not eventually settle in Canada, I have followed testimonies that seemed to illuminate the loyalist experience in revolution, exile, and settlement.

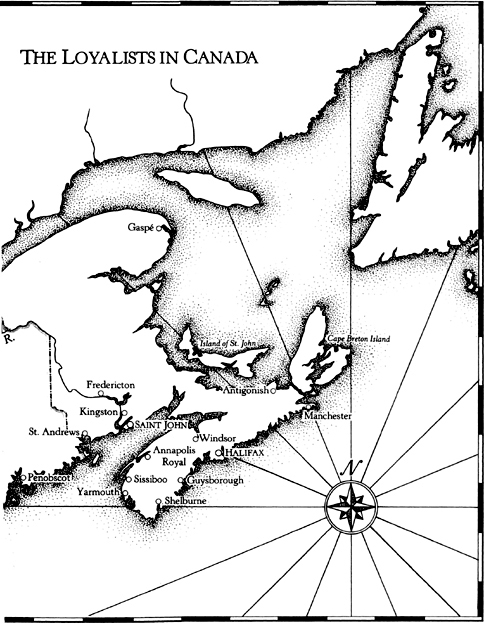

To reach beyond those few who wrote a lot and had their writings preserved, I have followed another, extraordinary source, the Loyalist Claims. After the American war, the British government announced it would hear claims and offer compensation to colonists who had suffered for their loyalty. Many of those who claimed had no particular wealth, fame, or position; those encountered in the extensive records of the Claims Commission include a barrelmakers widow trying to make ends meet in the newly founded city of Shelburne, Nova Scotia, a tenant farmer uprooted from the western frontier, and a war-ruined merchant trying to support himself as a household servant.

Some of the claimants merely presented an inventory of losses and their instructions for payment. Some wanted to tell war stories. And some used the commissioners time for an intricate examination of why they were loyal when their neighbours were not. All hoped to win financial compensation from a sometimes miserly commission. Their claims omitted much and distorted some of the loyalists experience, and most were composed in the formal, third-person style that the claimants believed or were told the officials preferred. Yet, in thousands of statements, the great array of individuals who claimed could hardly avoid presenting much about themselves, and I have quoted their petitions extensively.

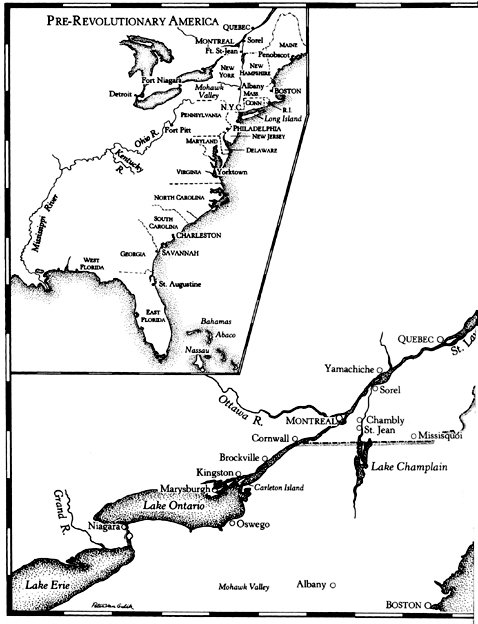

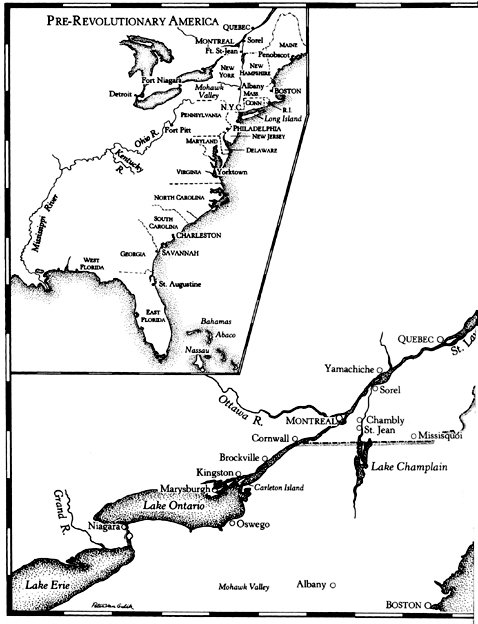

The war that created the United States drove at least fifty thousand colonial Americans into exile for the sake of their beliefs. Most of those refugees came to Canada. They assimilated into local societies, and became Nova Scotian or Upper Canadian, but they often preserved specific loyalist traditions too. In Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, in parts of Quebec, and in most of early settled Ontario, towns and communities founded in the loyalist migration have grown into cities or have persisted quietly in the rural fabric of the country. By numbers alone the loyalists command attention: conscious of it or not, many thousands of Canadians in every part of the country have loyalists in their family tree or loyalist communities in their background.

Still they have maintained their distance. Two hundred years after their arrival in Canada, every statement about the loyalists seems to begin with the announcement that they were not just wealthy and aristocratic Harvard graduates driven from Boston as tory tyrants. Indeed they were not, but rather than simply restating the negative, The Loyalists tries to reach those diverse loyalists of 1783 and 1784, and to follow their intricate routes to loyalty and to Canada.

Many individuals and institutions have assisted the research and writing of this book. Specific contributions are acknowledged in the endnotes, but I am particularly grateful to the Explorations Program of the Canada Council and to the Ontario Arts Council for grants in aid of my research, to my editor, Patricia Kennedy, and to my wife, Louise Brophy.

Note on the paperback edition: I have taken advantage of this new edition to make a few small additions and revisions to the 1984 text.

EXILE CAME EARLY FOR THOMAS HUTCHINSON .

Son of a long-established and well-connected family of Massachusetts merchants, and himself a youthful success in Bostons lively commerce, Thomas Hutchinson had entered colonial politics early and had risen rapidly. The people repeatedly elected him to Massachusetts colonial assembly, the Assembly placed him on the Governors Council, and the Governor made him a judge and then Chief Justice. Respected for his hard-headed financial management, valued for his political ability, supported by an expanding network of allies and relatives, Hutchinson rose steadily, for he seemed able to serve both the local interests of the elected representatives and the imperial policies of the royal government. Before he was fifty, he was virtually a colonial prime minister, key advisor to a royal governor dependent on local counsel.