Also in the

History of Canada Series

Death or Victory: The Battle of Quebec

and the Birth of an Empire, by Dan Snow

The Last Act: Pierre Trudeau, the Gang of Eight

and the Fight for Canada, by Ron Graham

The Destiny of Canada: Macdonald, Laurier,

and the Election of 1891, by Christopher Pennington

Ridgeway: The American Fenian Invasion

and the 1866 Battle That Made Canada, by Peter Vronsky

War in the St. Lawrence:

The Forgotten U-Boat Battles on Canadas Shores, by Roger Sarty

The Best Place to Be: Expo 67 and Its Time,

by John Lownsbrough

Death on Two Fronts: National Tragedies and the Fate

of Democracy in Newfoundland, 191434, by Sean Cadigan

Ice and Water: Politics, Peoples, and the Arctic Council,

by John English

Trouble on Main Street: Mackenzie King, Reason, Race,

and the 1907 Vancouver Riots, by Julie Gilmour

CONTENTS

| INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF CANADA SERIES |

Canada, the world agrees, is a success story. We should never make the mistake, though, of thinking that it was easy or foreordained. At crucial moments during Canadas history, challenges had to be faced and choices made. Certain roads were taken and others were not. Imagine a Canada, indeed imagine a North America, where the French and not the British had won the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Or imagine a world in which Canadians had decided to throw in their lot with the revolutionaries in the thirteen colonies.

This series looks at the making of Canada as an independent, self-governing nation. It includes works on key stages in the laying of the foundations, as well as on the crucial turning points between 1867 and the present that made the Canada we know today. It is about those defining moments when the course of Canadian history and the nature of Canada itself were oscillating. And it is about the human beingsheroic, flawed, wise, foolish, complexwho had to make decisions without knowing what the consequences might be.

We begin the series with the European presence in the eighteenth centurya presence that continues to shape our society todayand conclude it with an exploration of the strategic importance of the Canadian Arctic. We look at how the mass movements of peoples, whether Loyalists in the eighteenth century or Asians at the start of the twentieth, have profoundly influenced the nature of Canada. We also look at battles and their aftermaths: the Plains of Abraham, the 1866 Fenian raids, the German submarines in the St. Lawrence River during World War II. Political crisesthe 1891 election that saw Sir John A. Macdonald battling Wilfrid Laurier; Pierre Trudeaus triumphant patriation of the Canadian Constitutionprovide rich moments of storytelling. So, too, do the Expo 67 celebrations, which marked a time of soaring optimism and gave Canadians new confidence in themselves.

We have chosen these critical turning points partly because they are good stories in themselves but also because they show what Canada was like at particularly important junctures in its history. And to tell them we have chosen Canadas best historians. Our authors are great storytellers who shine a spotlight on a different Canada, a Canada of the past, and illustrate links from then to now. We need to remember the roads that were takenand the ones that were not. Our goal is to help our readers understand how we got from that past to this present.

Margaret MacMillan

Warden at St. Antonys College, Oxford

Robert Bothwell

May Gluskin Chair of Canadian History

University of Toronto

We are a democratic people.

George Brown, 1864

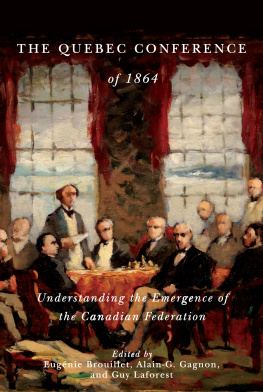

| ONE October 10, 1864: La Vieille Capitale |

Since Saturday we have had the worlds bleakest weather, lamented the Quebec City correspondent of the Montreal newspaper La Minerve on Monday, October 10, 1864. It is too bad for our visitors. Quebec City is so beautiful when the weather is good. Instead, on Saturday night, a white shroud of snow covered the ground, and a penetrating frost chilled us hand and foot. On Sunday, we might have been somewhere in Siberia. Today the white shroud has grown dirty, and you cannot put a foot off the sidewalk without plunging into mud. The wooden sidewalks were not much better than the streets. The English writer Anthony Trollope found while visiting that the boards are rotten, and worn in some places to dirt. The nails have gone, and the broken planks go up and down under the feet, and in the dark they are absolutely dangerous.

The visitors for whom La Minerve grieved were the delegates who had arrived for the British North American constitutional conference, beginning that morning at the legislative building. Thirty-three delegates

In the Province of Canada, a broad coalition committed to remaking the union took power in June 1864. In September, eight cabinet members from that coalition travelled by steamship to Charlottetown to present their proposals to delegates of the legislatures of the three Maritime provinces. In the brilliant sun of Charlottetown, the Maritimers endorsed confederation, a federal union of all the British North American provinces. Confederation carried the promise of westward expansion to British Columbia on the Pacific coast, and of rail links between the Maritimes and the Canadas. During the six days at Charlottetown, this confederation had generated a shared purpose among the usually fractious politicians of British North America. But they had discussed A longer meeting, a true constitutional conference, would be needed to discuss and ratify those terms of union, the principles and the practicalities upon which a new nation could be built. Early in October, British North American politicians were on the road again, this time to Quebec City.

In those days, they came usually by train. Quite suddenly, steam trains had become the way one travelled in British North Americabut not yet between Atlantic Canada and Quebec City. No rail line yet linked all the provinces of British North America. Fortunately steamships, as new as, almost as fast as, and often more comfortable than steam trains, filled the gap. The boats are very fine, wrote one traveller on the steamships that plied between Montreal and Quebec City in 1864, noting that they were three storeys high and like floating hotels, although they shake very much and the lamps swing with the motion, not agreeable.

For Maritimers travelling to the constitutional conference, a special steamship cruise had been arranged. In the 1850s, the province of Canada had commissioned a private shipping line to outfit three steamships to carry mail and tend the buoys and lighthouses of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. When the company got into financial trouble, the government found itself owning the ships. In August, the government steamer Queen Victoria had carried the Canadian cabinet from the dock at Quebec to anchorage in Charlottetown harbour in barely sixty hours. In early October,

Next page