KASHMIRS

THIN RED LINES

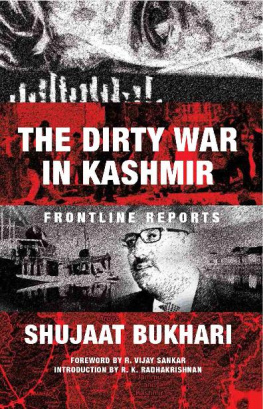

Dr Syed Shujaat Bukhari

Dr Tahmeena Bukhari

Copyright 2019 by Dr Syed Shujaat Bukhari, Dr Tahmeena Bukhari.

ISBN: | Hardcover | 978-1-5437-0505-8 |

Softcover | 978-1-5437-0504-1 |

eBook | 978-1-5437-0503-4 |

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

www.partridgepublishing.com/india

CONTENTS

Dedicated to

Dr Syed Shujaat Bukhari whose work will

continue to inspire us all.

Shujaat Bukhari, the noted journalist and policy analyst, was founder-editor of Rising Kashmir , one of Kashmirs two chief English language dailies. This fine compilation of articles is published after his tragic and untimely death.

We are fortunate that Shujaat was a prolific writer, of both chronicle and opinion, so that this collection could be published. Covering the years from 2013 to 2018, the book is divided into six sections: dialogue, India and its neighbours, Pakistan, Kashmir, killings and AFSPA, and local politics. Together, these six sections cover the key issues that dominated one of the grimmest periods in Kashmirs conflict-ridden history.

It is fitting that the book begins with a section on dialogue, an issue to which Shujaat returned time and time again, as an ardent advocate and frequent practitioner of peaceful negotiations to end the conflict in Kashmir. The opening article and those that follow reveal Shujaats rare quality of tempering humanism with realism, as well as his incisive knowledge of India and Pakistan and their battle over Kashmir. While pushing for talks, he believed that a single track between the Government of India and dissidents such as the Hurriyat Conference would not succeed until there was some rapprochement between the Governments of India and Pakistan. Thus, the book opens counter-intuitively, with advice against talks between the Government of India and the Hurriyat alone.

The bulk of articles in the first three sections focus on the rocky seesaw of India-Pakistan relations. Covering elections in India and Pakistan, with new and very different sets of leaders emerging, his articles detail repeated if short-lived hopes of every engagement between the two countries, in search of peace for Jammu and Kashmir. They make for sad reading, because they show that the two countries took immense confidence-building steps together, but each time were abruptly halted by militant attacks, religious nationalism and internal dissension. Gradually, Shujaat came to believe that confidence-building measures with the Pakistani army were the most critical game changers, even if they might be pro forma (DGsMO meet on December 24, 2013).

Section two adds further insights into the changing dynamic of India-Pakistan relations due to the impact of the war in Afghanistan, US plans for withdrawal and the emergence of a Russia-China bloc, along with Chinas Belt and Road Initiative and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Mentioning Chinas cautious support for calls to declare Gilgit-Baltistan Pakistans fifth province, Shujaat underlined Pakistans dilemma that such a declaration would weaken the latters case on Kashmir (GB, Kashmir and Pakistan, February 2015).

Chinas impact is a factor he returned to in later articles, pointing out that China, due to its significant and growing investments in Pakistan through CPEC, would continue to block Indias efforts at the UN to get the leaders, organizations and affiliates of Lashkar e Taiba and Jaish e Mohammad declared terrorist (June: Month of death and killings, 2017). Post-Pulwama developments bear out the truth of this prophesy.

The sharpest of his observations bear on Kashmir, as is to be expected. Tracing the renewal of militancy and public support for it which he dated from 2008 and the ensuing vacuum in the India-Pakistan peace process following the 26/11 Mumbai attacks Shujaat warned that Burhan Wani redefined the militancy in Kashmir and brought back its indigenous colour (Kashmir Funerals Writing on the wall, Renewed support to militancy, March 2016). If 2010 and 2016 were compared, he added, it should be noted that public support for militants had grown exponentially. Unlike 2010, when murmurs about peoples concern over continuous closure of educational institutions and the businesses were heard only after two weeks, this time Kashmir is silent over the future of students (Curfewed Kashmir, August 2016).

Pakistan, he said, may be the biggest promoter of violence in Kashmir, but the Government of India should also look inwards. Steps such as hanging of Afzal Guru, the demand for rollback of Article 370, the failure of the BJP-PDP coalition government, a new hardline approach to protest, rumors of separate townships for Kashmiri Pandits and Sainik colonies, had each contributed to public anger in the Valley, as had the rise in attacks on Muslims and Kashmiris after the BJP took power (New phase of insecurity in Kashmir, June 2016). Over a year earlier, in February 2015, he had predicted that the BJP-PDP alliance of 2014, which put a coalition government in place, constituted a far greater gamble for the PDP than the BJP. The PDP risked being decimated if the coalition failed, whereas its failure could strengthen the BJP in its core constituency since the BJP could claim they had tried but their partners Muslim intransigence doomed the alliance.

Yet, when Prime Minister Modi made conciliatory remarks to a delegation of opposition parties from Jammu and Kashmir led by former Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, saying that the killing of youth and security personnel brought distress to the people of India and called Kashmiris part of us, our nation, Shujaat was amongst the first to seek a ray of hope in these words. Not much may change with this development but time has not been lost if realization is kept in mind and a forward movement is pushed without any conditions, he said (Ibid).

As a Kashmiri positioned, inevitably, between India and Pakistan, Shujaat brought a unique perception of the latter country and its people, an asset that few policymakers in India paid sufficient attention to. His masterful dissection of Nawaz Sharifs speeches on Pakistans Kashmir Solidarity Day, in 2014, 2015 and 2016, provide an illuminating view of the internal political vicissitudes that Sharif faced both in relation to the Pakistan army and to India.

This positioning between India and Pakistan, however, also plunged him into a prolonged and agonizing tussle between realism and hope, which is reflected throughout this book. Discussing the surgical strikes at Uri, Shujaat pointed out that they were followed by de-escalation largely due to pressure by the international community. India and Pakistan may de-escalate for their own compulsions, he commented, but Kashmir remains unattended and is an open wound that would continue to give pain to its people (Kashmirs wails lost in war cry, October 2016).