Praise for the Book

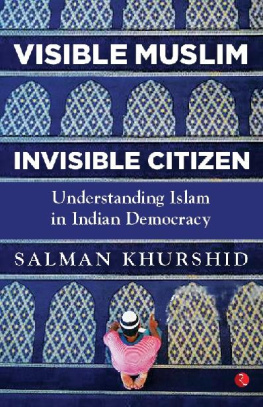

The inimitable Salman Khurshid attempts a spunky answer to not WHY I am a Muslim, but to WHAT I am as an Indian Muslim. This audacious book that seeks to both answer and raise questions about identity, citizenship and the stupendous project that India is, comes at a very crucial time. Now, much will depend on how we all choose to meet the challenges 2019 has thrown up, especially over the compositeness of India taken for granted, so far. Visible Muslim, Invisible Citizen confronts the camel in the tent and also counts the straws on its back.

Seema Chishti,

Author and Deputy Editor, The Indian Express

Visible Muslim, Invisible Citizen presents an unparalleled view of a political insider into the great debates about Islam and Muslims that continue to roil national life. This is a necessary book for understanding not just the predicament of a minority but that of religion itself in India.

Faisal Devji,

Author and historian

If a democracy is judged by the way it treats its minorities, the condition of the Muslims that is reflected in this book suggests that India is on its way to an ethnic brand of democracy.

Professor Christophe Jaffrelot,

Research fellow at CERI-Sciences Po/CNRS (Paris)

Published byRupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 20197/16, Ansari Road, DaryaganjNew Delhi 110002

Copyright Salman Khurshid 2019

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by them which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. Names of some people have been changed to protect their privacy.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-93-5333-XXX-X

First impression 2019

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The moral right of the authors have been asserted.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

To the village of Jarari in Farrukhabad,

That makes and unmakes Muslim leaders,

Not always understanding the impact of their decision on India.

and

Reshmi, Muskaan, Kajal, Khushboo, Ayesha, Muskaan II, Reena, Kashish and Gulsahansix angels from Farrukhabad who will break the glass ceiling, and Ranjoo Mann, who is helping them on that fascinating journey.

Contents

Preface

The thought of attempting another book on Muslims, having penned At Home in India three decades ago (with an updated version in recent years), came from reading Shashi Tharoors Why I Am a Hindu . Strictly speaking, a corresponding work should have been called Why I Am a Muslim, but there are theological and political reasons that pose fundamental problems for this book, which I dare say may not have arisen for the book that encouraged this one. Yet there is something in common to the extent that Shashi Tharoor and I are both, and remain interested in persons born as, Hindus and Muslims, respectively.

Curiously, our understanding of religion in modern India is as greatly influenced by Hinduism as we have known it over the years, as by what we see around us of late, the latter being a far cry from Sanatan Dharma, the core of the way of life described as Hinduism. It is further distorted into the aggressive political statement of Hindutva. In a sense, Shashi Tharoors job, though tough, was easier than mine. He essentially had to rescue Hinduism from its political misuse by a narrow ideological movement that exhibits several signs of fascism. It might not be wrong that he was speaking essentially to Hindus, although people of other faiths benefited from his exposition. For me, the task is a complicated mixture of explaining Islam to those who do not know enough about it; placing the identity of the Indian Muslim in the context of the Indian democracy; and deciphering the Muslim mind in social and political dimensions beyond theology. And curiously enough, it is a task undertaken primarily for the benefit of Hindus, many of whom in recent years have been forced to misunderstand Muslims and Islam. But it is also for the Muslims themselves, to help steer them out of this morass, partly of their own making. In pursuing this somewhat Herculean task, I may have to revisit the now-sterile debate that was once vigorously pursued by the late Syed Shahabuddinwhether it was right to speak of Muslim Indians or of Indian Muslims? The late diplomat-turned-politician and Muslim activist used his creation, the journal Muslim India , which predated Googles world of instant information, to collate and secure material on Muslims. However, Shahabuddin left us without making any conspicuous progress on his thesis, having, instead, earned unfairly the reputation of a conservative interested in Muslim exclusivenessa sort of intellectual mullah. A brilliant diplomat and a tireless campaigner for Muslim participation in the public space, he retreated into a small office in Okhla, from where he single-handedly edited Muslim India and managed the All India Muslim Majlis-e-Mushawarat (AIMMM), an organization of eminent Muslims. In his obituary, Shahabuddin was aptly described by the title of his unfinished autobiography, Muslim Heart, Indian Mind.

The genre of this book needs some explaining. Much as any author would desire to have his or her work taken seriously by the general readership as well as by experts and scholars, I believe I carry a special burden. Unlike books of dedicated academic scholars, this is neither the result of prolonged field research, nor a comprehensive response to the innumerable outstanding works in the area. Methodology of observation and collation of data are not offered for analytical contest. But it is also certainly not meant to be a collection of routine political responses to contemporary events and such history as might be reflected in them. In other words, it is not a political pamphlet. Furthermore, in contemporary India, views published in a book are either casually dismissed as mere reaffirmation of political opinions (in the loose sense) or interpreted as having been written with a hidden agenda or overt political motives. This questionable modus operandi is not necessarily a monopoly of party political adversaries, but also serves for friendly fire from ones own rival colleagues. Attempts to record the truth can therefore harm the author a great deal more than his enemies. But without seeking political martyrdom, I have, consistent with my convictions over time, spoken the truththe whole truth.

This book is about Islam as well as about Muslims, particularly Indian Muslims. In a sense, the two need not always be equated in a book, because it is quite possible to write about the two separately. I can claim to have understood the Indian Muslim by virtue of being one myself, having had close associations with many others variously placed in society, and in being, I believe, often incorrectly described as a Muslim leader. One wonders if leader of Muslims might have been any more persuasive of my capabilities as a public figure? But, of course, there lies the dilemma of our timescan one be a Muslim leader, and also be more, or must we choose between the two? Curiously, few other communities face this dilemma.