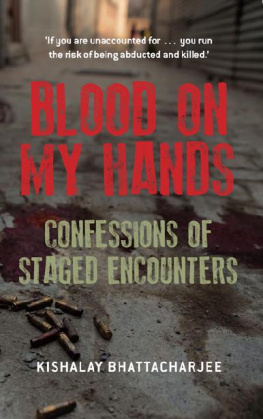

It is a winter morning in 2004, after the harvest festival in the month of January. It is the time for feasting and festivities. The sun is elusive and the air mostly wet and dull.

A police officer sits in his office in a district of Assam near the Bhutan border. He wears a moustache and a broad smile and is generally firm with his views, even if they offend others. He is an unlikely candidate for the job and hardly enjoys doing what he is expected to do. But he does it well; he does his job the way its meant to be done.

It has been an extraordinary season. The Royal Bhutan Army aided by the Indian Army, in one of the biggest covert operations ever in the northeast has dealt Assams twenty-five-year-old terrorist group, the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), a devastating blow. For years, Bhutan was a safe haven for armed separatist groups. No longer. The role of the Indian Army in the operation has not been made official, but it was there for everyone to witness. Not a single picture of this massive operation has been released. Along with ULFA, camps of other groups like the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) and the Kamtapur Liberation Organization (KLO) were also bombed, and there were mass surrenders by militants who were hounded out by air force strikes or so it was told.

Dressed in starched khaki, the police officer asks for lal cha or black tea, while talking to some visitors known to him. In Assam, lal cha is largely preferred to tea with milk. The visitors are passing on National Highway 52 and have stopped by to say hello to their old friend. Their conversation is mostly about the ongoing arrests and surrenders. A day earlier, a bus full of women in the ranks of ULFA as well as the wives of some ULFA cadres and leaders caught in Bhutan while fleeing the raids had arrived here. The police officer is now busy making arrangements for their accommodation and organizing legal procedures. The women look exhausted and some are accompanied by their children. Though the interaction is friendly, the officer is careful not to divulge anything official.

A young army captain is at the door and tentatively seeks permission to enter. He hesitates to speak but is assured that the visitors are the police officers own people; he can go ahead and talk without any worry.

This is embarrassing, but I have run into an overdraft, so is it possible to borrow some amount? I promise to return the favour as soon as possible, says the young captain.

The police officer, notwithstanding that visitors are around, assures the young man: My balance is rather low, but I hope I can transfer some amount to you by tomorrow morning. It is a tricky time, you see.

This cryptic conversation between a senior police officer and a young army officer in this eastern Indian state is not about borrowing money. It is a sinister exchange in the bizarre interplay of power, politics and violence.

Although money will inevitably change hands here, the currency is of human life and murder. The young officer is deployed in counter-insurgency operations and has killed two persons (tagged as militants in his official record), but inadvertently passed the telegraphic message to his senior command that three have been killed. He needs one more to make up for a typographical error. He has none in his kitty, so he requests the police officer to lend him a live victim.

The police officer casually asks him to come to the riverside early the next morning and take his advance. Bound, gagged and blindfolded, the victim will not struggle. He will be resigned to his fate like those before him. After he is taken to a suitably isolated location, he will be killed by a few rounds from army rifles fired at point-blank range. His body along with a story of an encounter which strains credulity will be produced and an ULFA cadre nomenclature issued to him. Photographs of weapons and foreign currency found on the body will be fed to an obedient press. The identity of this victim is unknown and will likely never be discovered. If he is identified, he will be officially recorded, at any rate, as a militant who had fired at the army patrol and was killed in the encounter which followed. In a climate of surrenders and bombings and shoot-outs, this one death will surely go unnoticed anyway; and thus another murder will be legitimized by the government record.

This is not a mere anecdote. It is a pattern of violence to which India has become inured. It is about impunity and the systematic replacement of the rule of law with lawlessness. It is such that even the parlance of this lawlessness which is no better exemplified than in the word encounter, with all its sickening connotations has entered Indias civil vernacular.

Max Weber notes that the relation between the state and violence is an especially intimate one, in which the state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. While Weber argues that violence is inherent to politics, Hannah Arendt states that violence is the opposite of power and is never legitimate. Be that as it may, the arbitrariness and criminality of State violence is a lived reality.

With State-sanctioned killings, there are martyrs and then there are criminals. But the large number of unknown, unnamed and even unclaimed men and women who have been hunted down by the State for its officials advancement or gratification is at the heart of this book.

Of those who have perished under this regime of perversion, vendetta and mistrust, we can name only a few. How many have died remains unknown and will never be publicly mentioned. Its victims have had no funeral rites. They have just disappeared, never to return, and their cries and screams have been heard but faintly. They are remembered only by family members, in conversation that is muted, colourless and regretful.

The anthropologist Michael Taussig asserts that cultures of terror are based on, and nourished by, silence. Silence has its varying degrees of expression. There have been regimes in living memory where people have accepted the bizarre and depraved just because it is familiar. Similarly, those in the northeast and the Kashmir Valley appear to have become acclimatized to an environment where extrajudicial killings are a routine occurrence, and the public in other parts of the country are accustomed to and even wearied by the bland, sanitized reports of encounters.

And unless death is at our doors, a stifled scream from afar barely registers. There was a time when a single wrongful death made news. Today, with the digital media awash with ghastly images from distant civil wars and the like, even the footage of ten encounter victims barely raises civil indignation. Even more worrying are the killings that occur in remote places, where almost nothing is known. What then is recorded is based on the conjecture of a few journalists. Such atrocities have only occasionally found their way to tiny newspaper columns or a few seconds television coverage. The rest have been blacked out of human history.

Memory and truth contest each other, and identities are blurred as the perpetrator claims to be the victim. But the silence that blacks out the hundreds should not consume the survivors, and that is why it is important to remember the dead.

![Bhattacharjee Sudakshina - Improve your global business english: [the essential toolkit for writing and communicating across borders]](/uploads/posts/book/205847/thumbs/bhattacharjee-sudakshina-improve-your-global.jpg)