Edward J Erickson - A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare

Here you can read online Edward J Erickson - A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury UK, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury UK

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Conflict | Number of Relocated Persons | Percentage of the Target Population Relocated | Type of Confinement | Deaths |

Acadian Rebellion | 7,000 | Over 50 | Permanent Exile | Unknown |

Navajo Removal | 9,000 | 8590 | Reservation | c. 1,500 |

Cuban Insurgency | 500,000 | Over 80 | Reconcentracin | 155170,000 |

Philippine Insurrection | 600,000 | Over 60 | Zones of Protection | 234,000 |

Second Anglo-Boer War | 115,000 (w)115,000 (b) | ConcentrationCamps | 26,000 (w)16,000 (b) | |

WWI Armenian Removal | Over 500,000 | Over 99 | Relocation Camps | c. 250,000 |

WWI Jewish Removal | 13,000,000 | Over 90 | Interior Cities & Towns | Unknown |

WWII Japanese-American Internment | 120,000 | Over 99 | Internment Camps | Very few |

Malayan Emergency | 225,000+ | Over 99 | New Villages | c. 3,000 |

Kenyan Emergency | 1,000,000 | Over 80 | Villagization | Unknown |

Algerian Insurgency | 2,350,000 | Over 30 | Regroupement Centres | Over 45,000 |

Conflict | Number of Relocated Persons | Percentage of the Target Population Relocated | Type of Confinement | Deaths |

Second Indochina War | 400,000 | About 5 | Strategic Hamlets | Unknown |

Portuguese Decolonization | 1,000,000+2,120,000 | Over 203015 | Aldeamentos | Unknown |

Notes

This figure does not reflect the 2,0003,000 Acadians previously removed from Acadia.

This figure does not reflect Boers living in cities and towns. The percentage removed of the rural population likely exceeded 95 per cent.

This figure reflects the number of relocated Ottoman-Armenians from the six Eastern Anatolian provinces and key cities on the lines of communications identified by the Ministry of the Interiors relocation directive of 31 May 1915.

This is a reasonable estimate of the death toll of Ottoman-Armenian population of the six Anatolian provinces and key cities who were relocated in 1915. The estimated 1915 death toll does not include the two subsequent periods of increased Ottoman-Armenian deaths (191822) or those who died in Russia.

No reliable figures exist for the total number or Russian Jews who were relocated. At least one million but, perhaps, as many as three million were forcibly evacuated. Within the Pale itself, a figure of 90 per cent relocated is not unlikely.

An additional 1,175,000 Algerians were relocated into existing Muslim villages. The combined total of some 3.5 million Algerians represented about 30 per cent of the total Algerian Muslim population.

Dorothee M. Kellou, A Microhistory of the Forced Resettlement of the Algerian Muslim Population during the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962): Mansourah, Kabylia , MA Thesis, Georgetown University, 2012, 82.

The official RVN/USG figure of 8,000,00010,000,000 living in Strategic Hamlets includes those who never moved but lived in villages designated as Strategic Hamlets. About 400,000 and 5 per cent of the countrys population represents the scholarly consensus on the actual number moved.

Portuguese Angola.

Portuguese Guinea.

Mozambique.

Major Christine Keating

But Contrary to their expectation the Gate was shut and they confined as Prisoners.

LIEUTENANT-COLONEL JOHN WINSLOW

Grand Pr, 16 September 1755

Introduction

The small church in the village of Grand Pr sat nestled at the heart of the community. For its Catholic, French Acadian congregants, the church represented the heart and soul of their efforts to make their land productive, to live peacefully with their Mikmaq neighbours and to remain free of earthly obligation to foreign rule. But on 5 September 1755, the church would become something else entirely: that symbol of salvation would become the prison in which 418 Acadian men and boys were held captive by British colonial troops. Lured there by the orders of Colonel John Winslow for a proclamation, it was there that the Acadian men would discover that they and their families were to be ripped from their land and deported, dispersed throughout the more southern British colonies in North America. Taking only what they could carry, their homes would be burned, their cattle commandeered, their farms settled by white families from New England.

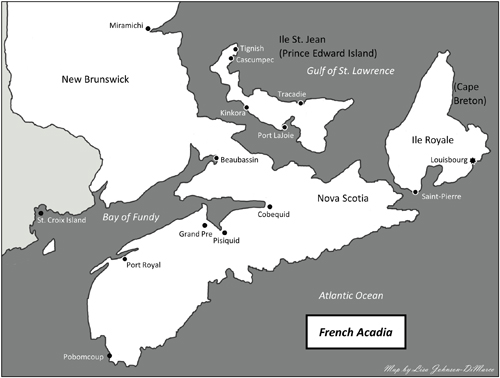

French Acadia 1755. Acadia was colonized by France in 1604 but was conquered by Britain in 1713. The permanent expulsions in 1755 forcibly emptied Acadia of nearly all of its French inhabitants. The modern Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island comprise what was Acadia. Many of the exiled Acadians moved to Louisiana where they are today known as Cajuns.

In the surrounding weeks and months, similar scenes would play out across Acadia. Ultimately, nearly 7,000 Acadians would be relocated, scattered throughout the British North American colonies.neighbouring Mikmaq indigenous people were passing information and supplies to French troops garrisoned nearby. When British troops discovered Acadians within the captured Fort Beausjour (later rechristened Fort Cumberland) in 1755, this proved their worst fears of collusion. Lieutenant Governor and Colonel Charles Lawrence decided the only way forward was to rid Nova Scotia of the Acadians entirely.

Throughout June and July 1755, Lawrence and New England Governor William Shirley devised a plan to expunge Nova Scotia of its formerly French inhabitants. This was a political decision, carried out by local colonial regiments and militia purpose-built for the operation. To say that the British expelled the Acadians is inaccurate; it was local colonial governments, charged with their own protection by a distant and disinvested mother country thousands of miles away, that devised and carried out a solution to the perceived Acadian threat. The Acadian expulsion was a military solution to a political problem, with financial and social benefits for Nova Scotia and New England. Decades of careful drainage and cultivation by farmers determined to make the coastal marshlands fruitful, made Acadian farmland particularly desirous. Acquiring that land for Protestant New England settlers became a priority, creating rich, religiously homogenous settlements and simultaneously securing a buffer zone against French attack by sea in the North Atlantic.

Although the political rhetoric surrounding the decision to expel the Acadians focused on the supposed security threat posed by the neutrals, the concept of military necessity is demonstrated here in a less developed, less distinct way than in later conflicts described in this book. Where later we will see military commanders executing relocations for strategic ends, sometimes predicated on political imperatives, in the case of Acadia, government and military decision making were one and the same. It was not the royal British standing army that marched on Grand Pr; it was local colonial regiments and militias called exclusively for that purpose by colonial governors William Shirley of Massachusetts and Charles Lawrence of Nova Scotia. Colonies were responsible for their own defence, and it was common practice at that time to muster militias for particular threats or campaigns (often against native populations). Thus the political exigencies of the day were the military exigencies of the day, and often vice versa. This was not a case of a military sent to occupy land and subdue a population, where the commander decided that the only way to achieve that end was through relocation; this was a military mission conceived of by political leaders who appointed commanders explicitly for the purpose of expelling the neutral French.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare»

Look at similar books to A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.