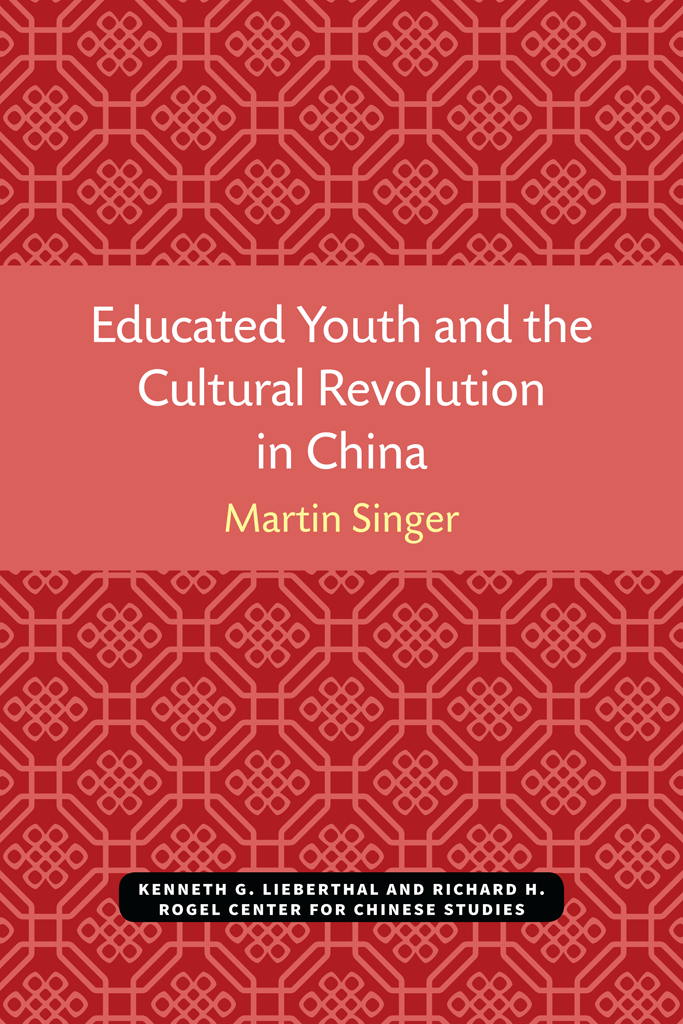

Martin Singer - Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China

Here you can read online Martin Singer - Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Kenneth G. Lieberthal and Richard H. Rogel Center for Chinese Studies, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China

- Author:

- Publisher:Kenneth G. Lieberthal and Richard H. Rogel Center for Chinese Studies

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES

MICHIGAN PAPERS IN CHINESE STUDIES

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China

Martin Singer

University of Michigan

Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies

No. 10

1971

Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program

Copyright 1971

by

Center for Chinese Studies

The University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-89264-010-2 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-472-03814-5 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12760-3 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90155-5 (open access)

The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Contents

The cultural revolution was an emotionally-charged political awakening for the educated youth of China. Called upon by aging revolutionary Mao Tse-tung to assume a vanguard role in his new revolution to eliminate bourgeois revisionist influence in education, politics, and the arts, and to help to establish proletarian culture, habits, and customs, in a new Chinese society, educated young Chinese generally accepted this opportunity for meaningful and dramatic involvement in Chinese affairs. It also gave them the opportunity to gain recognition as a viable and responsible part of the Chinese polity. In the end, these revolutionary youths were not successful in proving their reliability. Too idealistic to compromise with the bourgeois way, their sense of moral rectitude also made it impossible for them to submerge their factional differences with other revolutionary mass organizations to achieve unity and consolidate proletarian victories. Many young revolutionaries were bitterly disillusioned by their own failures and those of other segments of the Chinese population -- particularly the Peoples Liberation Army and the central leadership -- and by the fate of the middle school and college graduates of 1965, through 1967 many of whom were assigned to rural communes between November, 1967 and June, 1968.

In this essay an effort will be made first, to examine briefly pertinent elements of the Maoist vision of society, and then to examine basic locii of discontent among educated young people on the eve of the cultural revolution. Next the main body of the essay will be devoted to a relatively chronological review and reconstruction of the events of the cultural revolution as they affected young people. Finally, an attempt will be made to summarize and integrate the data and to achieve a fuller understanding of educated young peoples involvement in the cultural revolution.

Three aspects of Mao Tse-tungs personality as a leader are important to our understanding of his relationship with educated young people during the cultural revolution. First, Mao is a visionary. If this happens at a time of life when one is most vulnerable, because increasingly less able, to assert ones will and provide new meanings for that life the problem is even more acute.

An examination of Maos changing attitudes toward young people illustrates these points rather dramatically. Speaking in November, 1957, at the height of confidence in his vision, Mao told a group of Chinese students in Moscow:

The world is yours, as well as ours, but in the last analysis, it is yours. You young people, full of vigor and vitality, are in the bloom of life, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning. Our hope is placed on you... The world belongs to you. Chinas future belongs to you.

This sounds like a leader conscious of the movement of history, yet confident that his vision will survive -- carried on by younger people who share it. The failures of the Hundred-Flowers and the Great-Leap Forward period seem to have led Mao to some self-doubt. Less confident that his efforts would stand the test of time and transmission, he became more conscious of how long the revolutionization of Chinese

By 1964, the question of revolutionary successors was being dealt with rather frequently in the Chinese press. At the ninth Congress of the Communist Youth League, Hu Yao-pang revealed the doubts plaguing the leadership.

Since they have been brought up under conditions of peace and stability, it is easy for them to lapse into a false sense of peace and tranquility and to look for a life of ease and security. Because they have not been through the severe test of revolutionary struggle, they lack a thorough understanding of the complexity and exacting demands of revolution.

The emphasis on the need to justify sacrifice as well as doubts about youths ability to meet the challenges ahead were also reflected in another article in 1964, Bringing Up Heirs For The Revolution.

... It is a question in the final analysis of how to ensure that the revolution, won by the older generation at the cost of such sacrifice, will be carried on victoriously by the younger generation to come; that the destiny of our country will continue to be held secure in the hands of true proletarian revolutionaries; that our sons and grandsons and their successors will continue to advance, generation after generation, along the Marxist-Leninist and not the revisionist path...

The activist component of Maos character being so strong, one could assume that his pessimism could only reach so far before he would try to apply a corrective. The limit may have been reached at the time of Maos 1965 interview with Edgar Snow. In response to Snows question about the younger generation, which had been bred under easier circumstances:

He also could not know, he said. He doubted that anyone could be sure. There were two possibilities. There could be continued development of the revolution toward Communism. The other possibility was that youth could negate the revolution and give

Another key point for us to understand is the nature of the relationship between Mao and his people, especially the young people of China. Ruth Ann Willner has defined charisma as:

The absolute emotional and cognitive identification of a following with a leader and his descriptive, normative and perceptive orientation, i.e. the unqualified belief in the man and his mission.

In her general study of charismatic leadership she identifies Mao as a charismatic leader. If one accepts her definition, then by 1965 Mao would appear to have enjoyed a charismatic relationship primarily with the young people of China who had been reared on an intensive diet of Maos thought and, secondarily, with the Peoples Liberation Army which had recently been the target of Lin Piaos indoctrination efforts. Much of the Party leadership and cadres were operating within the Maoist vocabulary, but they were freely interpreting (Mao would say betraying) its content.

What was this revisionist drift that Mao detected in the six years before the cultural revolution? Mao felt that the CCP was becoming an entrenched bureaucracy and that this institutionalization of the revolution was changing its meaning. This was most specifically reflected in his inability to have his directions followed even in spirit. There were increasingly less veiled attacks on himself and his leadership. Finally and perhaps most importantly to Mao, there appeared to be a tendency among those assuming the bourgeois capitalist road to infect and corrupt the minds of youth.

It appears then that Mao turned to the youth of China for four reasons: (1) They were his greatest potential source of support, having been nurtured by his thought and knowing little or nothing of the negative results of applying that thought to reality. (2) That support was a power base from which to attack the revisionists of the Party and academic circles who were attacking his vision of society. (3) He had the opportunity to revolutionize an entire generation by involving them in a revolutionary mass movement. Mao had long been a firm believer in the necessity of doing something in order to know it.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China»

Look at similar books to Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.