Jos Antonio Primo de Rivera

Anthology of Speeches and Quotes

J OS A NTONIO

P RIMO DE R IVERA

A N T H O L O G Y O F S P E E C H E S A N D Q U O T E S

Antelope Hill Publishing

The content of this work is in the public domain.

First printing 2021

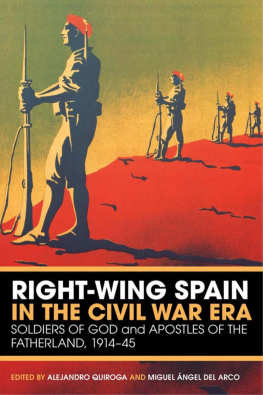

Originally published by Ediciones Prensa Del Movimiento Madrid in 1950, an arm of Cadena de Prensa del Movimiento, or Press Network of the Movement, a journalistic group and publishing house that belonged to the Falange Espaola Tradicionalista y de las JONS, the single party allowed in the Francoist state. During the transition from dictatorship to democracy, the Press Network of the Movement was renamed to the State Social Media and was continuously dismantled until its liquidation in 1984.

This work is being reprinted in English by Antelope Hill Publishing as it is an out-of-print work deemed worthy of preservation in physical form. The changes that were made were the moving of the glossary from the end to the beginning of the book and the inclusion of the Twenty-Six Point Manifesto of the Falange at the end as an appendix.

Cover art by sswifty.

The publisher can be contacted at

Antelopehillpublishing.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-953730-15-2 Paperback

ISBN-13: 978-1-953730-16-9 EPUB

T H E F A L A N G I S T O A T H

I swear to give myself always to the service of Spain.

I swear to have no pride other than that of the fatherland and of the Falange and to live under the Falange in obedience and joy, impetuousness and patience, gallantry and silence.

I swear fidelity and submission to our leaders, honor to the memory of our dead, and imperturbable perseverance amid all vicissitudes.

I swear, wherever I may be, in order to obey or in order to command that I shall respect our Hierarchy from the first to the last rank.

I swear to reject and give no ear to any voice of either friend or foe who might weaken the spirit of the Falange.

I swear to preserve above all the idea of unity: unity among the lands of Spain, unity among the classes of Spain, unity within the individual man and among the men of Spain.

I swear to live in holy brotherhood with all members of the Falange and to lend every assistance and eliminate every difference whenever this holy brotherhood requests that I do so.

C O N T E N T S

- The Idea of Empire,

I N T R O D U C T I O N

FROM THE ORIGINAL 1950 PUBLICATION

The compiler of this Anthology prefaced his work with an admirable introduction, which will be read with advantage by those who are acquainted with Spanish. This version, however, is intended for those who do not read that language, to most of whom Jos Antonio Primo de Rivera is only a name; a name at times confused with that of his father General Primo de Rivera, or even unknown altogether. The original introduction was written for the Spanish people, to whom Jos Antonio is a household word, and his portrait, exhibited everywhere in the country, is as familiar as that of General Franco himself.

It seemed best, accordingly, not to translate Sr. Torrentes introduction, much of which would inevitably leave the English-speaking reader at a loss; but to substitute the present sketch. In compiling it, the translator has avoided any attempt at a literary essay; still less does he seek to pass judgement on Jos Antonio as a historical or political figure. He has only sought to provide that framework of facts which will enable the reader to follow the course of the Anthology without getting puzzled on points of detail, and to appreciate Jos Antonios doctrines more fully by an acquaintance with the environment in which they were expressed and out of which they arose. Those, therefore, who are well informed on the history of recent Spanish politics and thought are asked to excuse the repetition of facts already familiar to them but perhaps indispensable to others.

A skeleton of Spanish history over the last 30-odd years might be constructed as follows. In the Great War of 1914-18, Spain was neutral. She had no direct interest involved. She was still weak and depressed after the loss of her last American possessions, Cuba and the Philippines, in 1898. There were pro-Allied and pro-German groups in the country, but no real question of entering the war arose. Her internal condition continued to decay. In 1923 the country seemed to be sliding into imminent ruin, and King Alfonso XIII entrusted General Primo de Rivera with dictatorial powers to pull it together. His dictatorship, mild and patriarchal, restored peace and stabilized the nations economy. In the material sphereroads, railways, public works and the likehe achieved wonders, and produced the same kind of results. At about the same period, as visitors to Italy universally recognized in the early years of Mussolinis power there, efficiency, administrative honesty and cleanliness replaced the ancient corruption. A regime, however, stands or falls by more than such exterior manifestations. Everybody may judge the Dictatorship for himself: how Jos Antonio, the Dictators son, a son entirely devoted to his father, judged it, will be found in this book. We will merely record that Jos Antonio was never so much as a member of the Generals Union Patritica.

After the fall of General Primo de Rivera in 1930, the political situation again became confused and full of unrest. Republicanism was rife, and on April 14, 1931, King Alfonso formed the opinion that it was incumbent on him to retire from Spainhe did not abdicatein order to avoid civil strife and bloodshed. The King and the Royal Family then left Spain, and the Republicans took power without any resistance.

This date, April 14, 1931, is a cardinal one and must he borne carefully in mind in order to appreciate a great many of the extracts in this book, and indeed a large proportion of Jos Antonios thought in general. There are two main points in this connection which must he stressed. First, the Monarchy was not overthrown constitutionally, so to speak, by any victory of a Republican party at a general election, at which the issue of Monarchy or Republic was before the electorate. There were, to be sure. Municipal Elections in progress, and many candidates were, in fact, persons of Republican opinions. The early results of these local government polls, in Madrid and certain other large cities, returned a majority of councilors adhering to the Republican groups. The Monarch left Spain forthwith, without waiting even for the final results, which showed a large majority of Monarchist councilors over the country as a whole. Spain was thus faced with a situation surely without precedent in the history of monarchies: a King abandoned his realm in the middle of an election which lacked competence to express the peoples will for him to go, and which in fact returned a majority of his supporters.

The second fact about April 14, 1931, a fact continually referred to by Jos Antonio, is the alegria, as he calls it (light-heartedness, gaiety, cheerfulness) of the country as a whole. For the diehard Monarchists, it was of course a day of gloom and grief, aggravated by a number of Republican demonstrations of an extremist type. For out-and-out Republicans, it was a day of wild and even rowdy triumph. But Jos Antonio makes it clear that he is not referring to the latter, but to the cheerful air of anticipation that was abroad among the general mass, even among many who felt personally grieved to see the Monarchy fall. The date of April 14th, 1931 promised the Spanish people that at last their revolution was going to be carried through; that is, the revolution towards social justice. These bright expectations were not fulfilled.

Next page