S ELLING THE S IGHTS

Early American Places is a collaborative project of the University of Georgia Press, New York University Press, Northern Illinois University Press, and the University of Nebraska Press. The series is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more information, please visit www.earlyamericanplaces.org.

A DVISORY B OARD

Vincent Brown, Duke University

Andrew Cayton, Miami University

Cornelia Hughes Dayton, University of Connecticut

Nicole Eustace, New York University

Amy S. Greenberg, Pennsylvania State University

Ramn A. Gutirrez, University of Chicago

Peter Charles Hoffer, University of Georgia

Karen Ordahl Kupperman, New York University

Joshua Piker, College of William & Mary

Mark M. Smith, University of South Carolina

Rosemarie Zagarri, George Mason University

S ELLING THE S IGHTS

The Invention of the Tourist in American Culture

WILL B. MACKINTOSH

New York University Press

NEW YORK

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mackintosh, Will B., author.

Title: Selling the sights : the invention of the tourist in American culture / Will B. Mackintosh.

Description: New York : New York University, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017054989 | ISBN 9781479889372 (cl : acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: TourismSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory19th century. | TouristsUnited StatesHistory19th century. | TravelersUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Popular cultureUnited StatesHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC G155.U6 M3 2019 | DDC 306.4/8190973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017054989

C ONTENTS

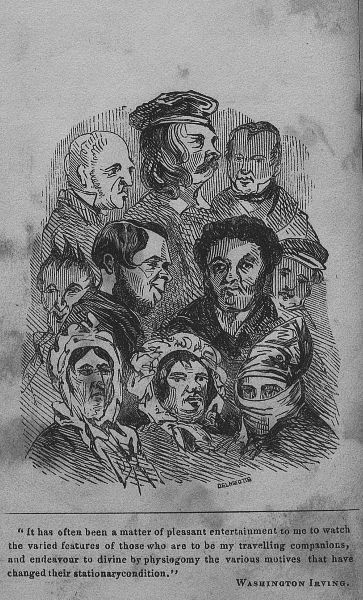

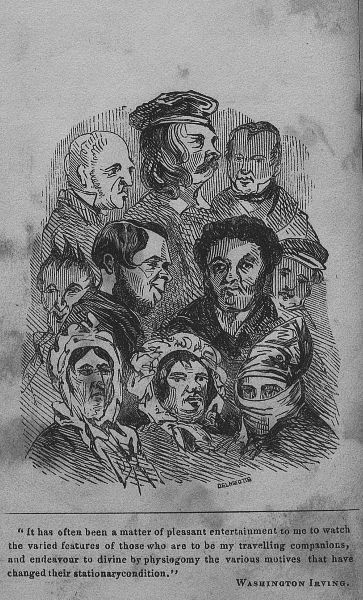

In the spring of 1847, the well-known British engraver Frances Delamotte decided to publish a popular illustrated volume on the subject of travelling and travellers. Being more an artist than a writer, Delamotte asked his friend E. L. Blanchard, a famous writer of Drury Lane pantomimes, to supply the text. Blanchard complied, and in an astonishing six weeks he produced a slim, lighthearted work that he dubbed a physiology... of travelling and travellers. In it, he sought to present an animated picture of that unceasing movement which is constantly impelling mutable humanity forwards and backwards, upwards and downwards, left and right, over the solid, or fluid, or gaseous portions of the world. He gave his book the bombastic but prescient title Heads and Tales of Travellers & Travelling: A Book for Everybody, Going Anywhere. The Sunday Times called it exactly one of those books that every one ought to read, and many evidently did, because it remained in print on both sides of the Atlantic for a decade. It was an ephemeral piece of commercial entertainment, but the topic was well chosen and the timing was right, and its authors were amply rewarded.

Delamottes proposed subject of travelling and travellers, and the physiology template that Blanchard used to structure the book, were not chosen thoughtlessly. By the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the speed, distances, and modes of travel were all exploding, thanks to technological and market innovation and to relative peace in the Atlantic world after Napoleons fall at Waterloo. Contemporary observers

As befit a physiology, Blanchard dissected the traveling body politic and analyzed its constituent parts. He examined different modes of travel, categories of destinations, and, most importantly, types of travelers. He drew distinctions between the disciples of pedestrianism and the new breed of commercial travelers. From both, he distinguished tourists as a kind of traveler who merely travels for the sake of travelling. It was the tourist who had pride of place as the subject of Blanchards first chapter, which suggests the outsized significance of this relatively new category of people on the road. But Blanchards work was a literary pantomimelighthearted, comical, and topicalrather than a serious work of social analysis. This book takes seriously the project that Blanchard undertook facetiously, by explaining the origins and cultural significance of the distinctions he made among travelers at midcentury, and by explaining the emergence of a new category, the tourist, in nineteenth-century American culture.

At the opening of the nineteenth century, few observers made sharp linguistic or cultural distinctions between the different types of travelers they observed on the roads, rivers, and seas of the early American republic. The word tour had been used in English to describe traveling since the mid-seventeenth century, and it spawned the word tourist around the turn of the nineteenth century.

F IGURE I.1. Frances Delamottes visual physiology of traveling types, from the frontispiece of Heads and Tales of Travellers & Travelling. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

The meanings of the terms traveler and tourist began to diverge in the 1820s, as an emerging national market economy began to reshape the availability of geographical knowledge, the material conditions of travel, and the number and variety of destinations that sought to profit from visitors with money to spend. These interrelated developments, all pushed by a generation of ambitious boosters and entrepreneurs, began to transform the critical steps of travelincluding choosing a place to go and obtaining the knowledge and the means to get thereinto commodities that could be produced in volume and sold into a potentially national marketplace of consumers. The commodification of these components happened gradually and unevenly across the territory of the United States and the decades of the nineteenth century: certain print genres of geographical knowledge were more efficiently produced by industrial publishing firms than others; some routes of travel supported large-scale transportation businesses before others; and accessible destinations with appealing natural features attracted more visitors than did obscure and featureless resorts. The routes and technologies deployed by both the print and transportation industries tended to spread westward and southward from the major northeastern port cities, and thus their commodification took place earlier in the Northeast and the Old Northwest than they did in the Deep South and the Old Southwest. Because the commodification of print and travel was gradual and uneven, so too was the movement toward distinct meanings for traveler and tourist to which it gave rise. The term tourist was used by some authors to disparage British travelers in the early decades of the century; some guidebooks still hailed their audience as travelers on the eve of the Civil War; and some observers continued to treat them as synonyms, especially when writing casually. But by the time Blanchards literary burlesque hit the shelves of American booksellers in 1847, pleasurable travel experiences were widely available for purchase by elite and middling Americans, and the consumers who bought such experiences were generally termed tourists and understood to be a separate and identifiable subset of the traveling public.

Next page