History, Society and Land Relations

First published in January 2010

E-book published in September 2019

LeftWord Books

2254/2A Shadi Khampur

New Ranjit Nagar

New Delhi 110008

INDIA

LeftWord Books is the publishing division of Naya Rasta Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Rights to this work rest with Communist Party of India (Marxist), and it is published under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 India license. For details of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/in/

leftword.com

Contents

by V. K. Ramachandran

The publisher would like to thank V. K. Ramachandran, T. Jayaraman and Prakash Karat for their help in making the selection for this volume.

The publisher would like to gratefully acknowledge the following publications, from which the essays in this volume are taken:

On Historical Materialism. Introduction to History of Indian Freedom Struggle by E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Trivandrum: Social Scientist Press, 1986.

Marx, the Asiatic Mode and the Study of Indian History. E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Selected Writings , Vol. I, Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1982.

Adi Sankara and his Philosophy: A Marxist View. Social Scientist , Vol. 17, No. 12, Jan.Feb. 1989.

Classes and Class Struggle in Indian History. Social Scientist , Vol. 22, No. 910, Sept.Dec. 1994.

The Class Character of the Nineteenth Century Renaissance in India. Social Scientist , Vol. 24, No. 910, Sept.Oct. 1996.

Class Character of the Nationalist Movement. Social Scientist , Vol. 4, No. 1, Aug. 1975, The National Question in India Special Number.

The Indian National Question: Need for a Deeper Study. Social Scientist , Vol. 10, No. 12, Dec. 1982.

Castes, Classes and Parties in Modern Political Development. Social Scientist , Vol. 6, No. 4, Nov. 1977.

Once Again on Castes and Classes. Social Scientist , Vol. 9, No. 12, Dec. 1981.

Caste Conflicts vs. Growing Unity of Popular Democratic Forces. Economic and Political Weekly , Vol. 14, No. 78, Annual Number on Class and Caste in India, Feb. 1979.

The Marxist Theory of Ground Rent: Relevance to the Study of Agrarian Question in India. Social Scientist , Vol. 12, No. 2, Feb. 1984, Marx Centenary Number 3.

The Question of Land Tenure in Malabar. E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Selected Writings , Vol. II, Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1985.

A Short History of the Peasant Movement in Kerala. E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Selected Writings , Vol. II, Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1985.

Marxism-Leninism and the Bourgeois Judiciary. E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Selected Writings , Vol. I, Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1982.

Talking about Kerala: A Conversation with E.M.S. Namboodiripad by V.K. Ramachandran. Frontline , Vol. 15, No. 09, April 25May 08, 1998.

The rights to EMSs writings rest with the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and the present volume is being published under a Creative Commons license, which allows for these writings to be further disseminated under an identical license for non-commercial purposes with due attribution.

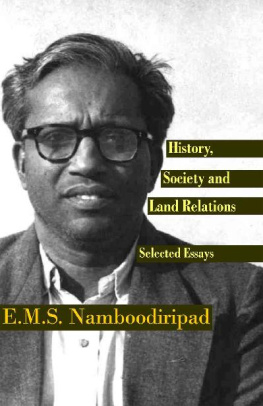

E.M.S. Namboodiripad (19091998) left behind an enormous legacy, both in theory and in practice. As a young man, EMS was inspired by the freedom movement, to which he gave his energy in his native Kerala. Born into a family and community at the fortunate end of the feudal system, EMS threw himself early into undermining its foundation. His early writings in Unninamboothiri were against what EMS later called the jenmi -landlord system. Nothing would have pleased him more, he felt, than to make the Namboodiris into human beings. It was a vast assignment for a young man, but EMS was up to it. Not for him only scholarly combat. EMS threw himself into the movement for freedom, first into Gandhis Congress, then into the Congress Socialist Party and finally into the Communist movement. The political domain provided EMS with a wider canvas within which to push against the curious combination of feudal and capitalist power in colonial India.

EMS encountered Marxism in the mid-1930s, when he was already involved in building a socialist movement in Kerala. Within a few years, he had taken his lessons from Marxism to write a minute of dissent to the report of the Malabar Tenancy Enquiry Committee ( in this volume), helping build one of the strongest Kisan Sabhas in the country. EMS would later be the Joint Secretary of the All India Kisan Sabha and he would play a very significant role in the writing of the CPIs 1954 resolution, Our Tasks among the Peasant Masses . There was no mechanical application of Marxism as dogma; for EMS, Marxism remained alive, a method by which to interpret the history and society of India.

It is this suppleness that defines EMSs account of the history of the Malayalam-speaking people. Here EMS drew from the Marxist theory of nationalities to creatively apply it to the Indian context. The Malayalam essay, One and a Quarter Crore Malayalees (1945), was later expanded into English as The National Question in Kerala (1952). EMS drew from his own historical research to provide the basis for his advocacy of Aikya Kerala , United Kerala (the unity of Travancore, Cochin and Malabar into the modern state of Kerala). See in this volume, which summarizes his earlier approach. What is essential to grasp about EMSs oeuvre is his spirit of infusing Marxism into history.

Already by the 1940s, EMS wrote on a range of issues, from agrarian relations to language questions, from Indian history to contemporary matters. This array would deepen as the years went on, with EMS writing with fluidity on questions of the ancient world to questions of immediate political relevance. He was able to engage with professional historians and professional politicians with equal gravity, and this is evident in the fifteen essays collected in this volume. Book reviews of works by Irfan Habib and K.N. Panikkar ( in this volume). The humble work was not as modest as EMS claims. He read widely, from Indian historiography to the various currents in Marxism (including, toward the end of his life, the work of Antonio Gramsci). EMS also engaged with the questions of the general public, answering their queries in a daily column for Deshabhimani . Nothing escaped his attention; everything warranted a thoughtful response.

EMSs writings cover a large number of themes. In this volume we have restricted the selection to essays on history, society and land relations. Even here there are remarkable asides on the general character of Indian social development, and on Marxist theory. But there is something that holds these essays together. The unity is not simply dialectical and historical materialism; it arises out of an understanding of the remarkable continuities in Indian history, where rather than revolutionary transformations we see superimpositions. How does one account for this continuity? European observers during the colonial times attributed this to the fact that Indian society was made up, according to them, of village republics, which remained more or less unchanging even when there was political upheaval at the top which led, every once in a way, to change in ruling dynasties. Marx contemplated this question as well, and, to explain the lack of development of capitalism in India came up with the formulation of the Asiatic Mode of Production. EMS was drawn to this concept, but not uncritically. He was persuaded by the historical research (especially of Marxists like D.D. Kosambi and Irfan Habib) that Marxs concept did not fit Indian society in quite the way Marx had formulated. Yet, EMS did not entirely abandon the kernel of the concept eitherwhich was to seek an explanation for the continuity that characterizes Indian history (indeed, Eric Hobsbawm refers specifically to EMS in his writings on the Asiatic Mode). Central to this continuity, EMS felt, was the institution of caste. As EMS puts it in The Indian National Question, included in this selection: