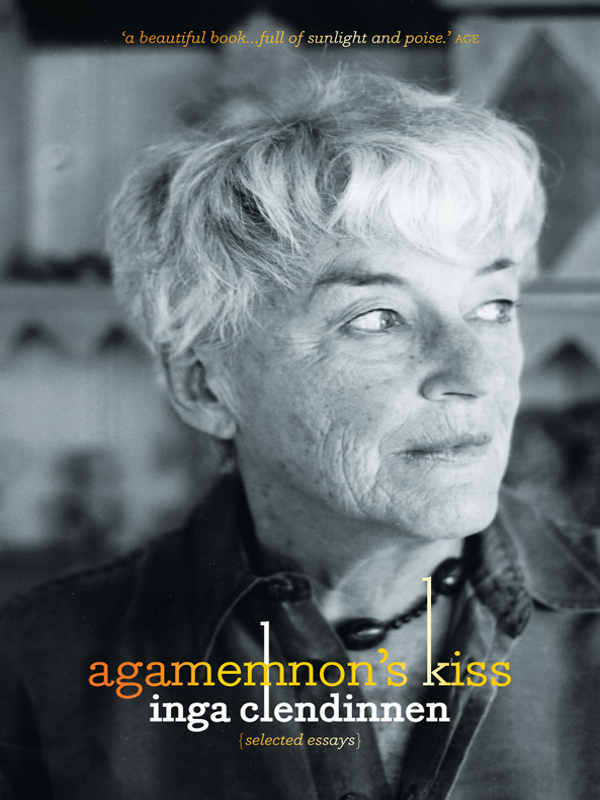

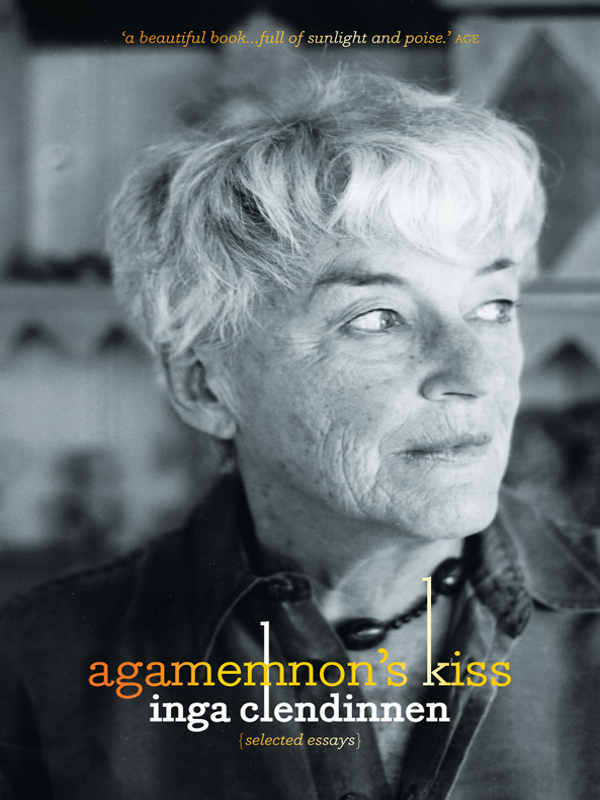

AGAMEMNONS KISS

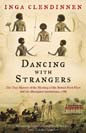

INGA CLENDINNEN

was born in 1934. She is a distinguished historian of the Spanish encounters with Aztec and Maya indians of sixteenth-century America, and author of Reading the Holocaust, named a New York Times best book of the year and awarded the New South Wales Premiers General History Award in 1999. Her 1999 ABC Boyer lectures, True Stories, were published in 2000, as was her award-winning memoir, Tigers Eye.

In 2003 Dancing with Strangers, her history of the meeting between the original inhabitants of Port Jackson and the British settlers of the First Fleet, was published. The following year it won the Kiriyama Prize for non-fiction, the NSW Premiers Literary Awards (Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-Fiction), the Queensland Premiers Literary Awards (Best History Book) and was shortlisted for the Age Book of the Year, the Courier-Mail Book of the Year and the Victorian Premiers Literary Award for non-fiction.

CONTENTS

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright Inga Clendinnen 2006

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in 2006 by The Text Publishing Company

This edition 2007

Designed by Chong

Typeset in Granjon by J&M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia Cataloguing in Publication data:

Clendinnen, Inga.

Agamemnons kiss : selected essays.

ISBN 978 1 921145 86 5.

1. Australian essays - 21st century. I. Title.

A824.4

In memory of my unknown donor, April 1994,

and of Helen Daniel 19462000

My thanks, as always, to Michael Heyward

and the team at Text

A little over sixteen years ago my old life was ended by severe illness. Four years later I was given a new life through the skill of the Liver Transplant Unit at the Austin Hospital and the kindness of a stranger. For the first weeks after the operation I felt like a hatchling escaped from its tight, white, silent world into this great, vivid, pulsing one. The exhilaration lasted for months. Then I sobered (though not, Im happy to report, completely) and began, as they say, to consider my position. Clearly my university life was over, and with it the joys of conversations with colleagues, and the incomparable pleasure of guiding intrepid students into the mental worlds of Aztec and Maya Indians. My own explorations into those worlds were also over: my doctors forbad me to return to Mexico. My children were grown and gone. Now my occupation was gone, too.

I think prolonged illness must always do thatput an end to the stories you had been telling yourself about your life. But even while I was still in hospital there had been intimations of a possible new story. Early in my illness I had bought a laptop, in part as talisman from my old life, in part to fill the empty days. I wrote about the horizontal people around me, and some of the vertical ones too; about the memories that came drifting from childhood in the silence of the night and stayed to haunt my days. A woman named Helen Daniel who had reviewed my book on the Aztecs came to visit me, became my friend, and chivvied me into writing more (I tell something of this in the essay called Backstage at the Republic of Letters). Helen didnt seem to care what I wrote so long as I kept writing, which is a long way from academe. So I wrote a very short story about strangers on a train and a longer one about a sour old woman; they won prizes; I was back in the turning world again. Another woman who knew my Mexican work asked me to write something for a collection of essays she was putting together: I wrote About Bones. My new life had begun before I knew it.

Since then I have written four books: Tigers Eye, which recorded what it feels like to fall into the underworld of sickness and then to clamber out again, one on the Holocaust to exorcise some of its horror by steady looking, and two on the relations between sea-voyaging British and land-voyaging Australians from their first meeting in 1788. If I had not fallen ill I would have written none of them. I also wrote essays, some in parallel with the books, some at tangents from them, and some about the accidental collision between a particular thought and a particular moment in time.

I like writing essays because they are short, as I now know life is. They are also about the right length for the way we live now: for reading in waiting rooms, between planes, on planes; for putting yourself to sleep at night; for thinking about when you cant sleep. But it is only now that I have been instructed to write this introduction that I begin to wonder what these things called essays are. My dictionary is not much help. It tells me that essay. n. means Attempt (at); a literary composition (usu. prose & short) on whatever subject; and that essay, v. t. means to try, test (person, thing), to attempt. These things piled in front of me are short, they are certainly not poetry, they are on a bewildering array of subjects. They are also, heaven knows, attempts. They do not look like finished work at all. Sometimes they end with a question mark. But what else are they?

The odd thing is that I know what essays are not. I know you cant preach in an essay because it turns into a sermon; you cant teach in an essay because it turns into a lecture; you cant exhort in an essay because it turns into a harangue, and you cant dredge the mud at the bottom of your soul because then it will turn into a confession. In the dry-mouthed panic of a radio interview I once said that essays were like love affairs, meaning they were intimate, brought unexpected pleasure and usually didnt last very long. Now I realise they are nothing like as intense as a love affair, and that that is their quality. Nothing much hangs on them beyond the pleasure we take in them. A friend suggested they were like eighteenth-century letters: a pleasurable, elegant pastime for a rainy afternoon. Its true that eighteenth-century letters were not private. The letter-writers knew their letters were likely to be read aloud before a family or some larger company. But by the nineteenth-century letters had lost that public dimension, and that creates a problem. Chekhov and Flaubert wrote many letters, but they would never have consented to our reading them. For one thing, they were artists. (Flaubert could spend a whole day on a sentence. We know that from a letter.) They would not want us to see them in a state of literary undress. More important, their letters are hand-crafted for a particular recipient. To his brother Chekhov writes gaily and tenderly; to his accountant wittily and sometimes crossly. Embarked on his Egyptian adventure Flaubert writes to his mother (he calls her Darling, and means it) swearing he is keeping himself healthy, warm, clean and well-rested. Meanwhile he is boasting to a friend left sulking in Rouen of his lascivious exploits with the local whores, especially the famous courtesan Kuchuk Hanem. He also remarks that he has picked up yet another dose of the clap.

Reading letters addressed to other people might be endlessly beguiling, but it is a shabby thing to do. Our punishment for it is watching all that affection, all that verve and wit, flowing to some other person, and knowing it will never, never be directed to us.

Next page