First published in Great Britain in 2005 by

Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street,

Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Originally published in Australia in 2003 by

The Text Publishing Company, Melbourne

Copyright Inga Clendinnen, 2003

The moral right of the author has been asserted

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84195 699 2

eISBN 978 0 85786 763 6

Design by Chong

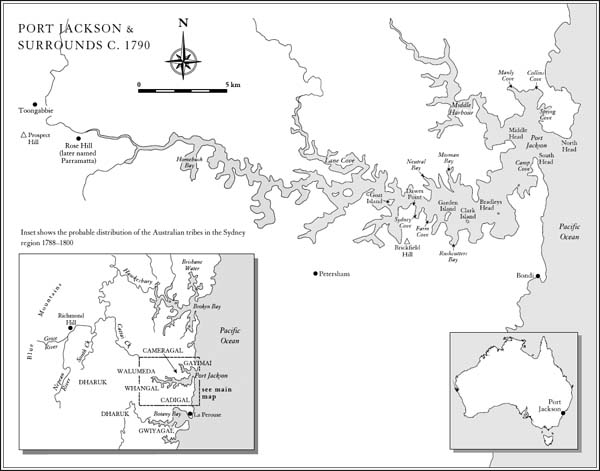

Map by Tony Fankhauser

Typeset in Granjon 12.2/17 by J&M Typesetting

This digital edition first published in 2012 by Canongate Books

www.canongate.tv

For

Anastasia

and for

Gilchrist

PREFACE TO THE UK EDITION

Late in January 1788 a British fleet made landfall at Botany Bay and then at Port Jackson, on the south-east coast of Australia. Their cargo was convicts; their task to create a self-sufficient society on those remote, unpropitious shores.

The expedition was led by Commander Arthur Phillip of the Royal Navy. Phillip was a most unusual imperialist. Like most of his officers he was a child of the English Enlightenment: scientific in observation, critical in analysis, fastidious in record. Unlike most of his fellows, he was also a restless, even reckless, thinker. In recognition of the colonys isolation he had been given close to absolute power. Within the settlement he would use that power with judgement and finesse. When he went home at the end of his five-year term, he knew the colony would survive.

A subsidiary requirement of settlement, little pressed, was dearer to his heart. He was determined to establish his colony at the least possible cost to the people whose lands he was entering. He wanted nothing material from them: he brought both provisions and labour with him, while the slice of land the British occupied was uncultivated, and consequently, he thought, there for the taking. What he wanted from the Aboriginal Australians was a rarer commodity: their trust. Phillip believed that all men, whatever their colour or custom would, after a period of tutelage, recognise the benefits of civilisation encapsulated in the moral beauty of British law a law, as we now realise and as Phillip did not, evolved from centuries of agrarian and pastoral pursuits and pivoting on the twin principles of the protection of property and the rights of the individual.

The people Phillip and his men met on the harbour beaches were nomads, moving lightly over their land, carrying with them few possessions beyond an intricate law forged out of millennia of experience of human survival in Australia, that driest, most recalcitrant of continents.

The British passion for scrupulous documentation provides a detailed record of what happened next.

Acknowledgments

I thank the staff at the Borchardt Library, La Trobe University, and at Townsville Regional Library, whose kindness went well beyond duty.

I thank Michael Heyward at Text for luring me into this adventure in the first place. He promised I would enjoy myself, and I have. He has proved yet again an incomparable editor.

I thank my old colleagues at La Trobe University History Department for their continuing affection and interest over the years, especially Alan Frost, John Hirst and Richard Broome for generous aid and comfort.

I thank the host of writers who will find no acknowledgment in the text, but who have filled my days and shaped my thinking over the years.

And I thank Miss Cantwell, third-grade teacher at Newtown and Chilwell State School sixty years ago, who finally managed to teach me to read.

Man proceeds in a fog. But when he looks back to judge people of the past, he sees no fog on their path. From his present, which was their far-away future, their path looks perfectly clear to him, good visibility all the way. Looking back he sees the path, he sees the people proceeding, he sees their mistakes, but not the fog.

Milan Kundera

INTRODUCTION

This is a telling of the story of what happened when a thousand British men and women, some of them convicts and some of them free, made a settlement on the east coast of Australia in the later years of the eighteenth century, and how they fared with the people they found there.

My telling of it has its origins in a place, and in a person. For the place: a few years ago I took a boat trip with my husband across the top of Australia. We stopped briefly at a place called Port Essington, or Victoria, on the Cobourg Peninsula. Nowadays it is a rangers headquarters, but it was built and garrisoned in the first half of the nineteenth century as a fort against the French. The French didnt come, and after about eleven years the soldiers were withdrawn.

It is desolate country, hot, sweaty and, despite its flatness, somehow claustrophobic. The sea up there glitters like new silver, but its full of crocodiles. Even the tough young ranger didnt swim, despite the heat, despite the boredom. He said the crocodiles were too crafty. If you went in at the same place twice the odds were one of them would be waiting for you, and they would pick up the sound of the splashing anyway and slide along to check out the prospects. He also warned us about the snakes, and listed some of the diseases the local mosquitoes were eager to trade for a sip of human blood. There wasnt a lot to do. We looked through the tiny museum, peered into a couple of the dark little stone houses where the married soldiers used to live, and walked a long hot way up to the cemetery. It was a big cemetery for so small a place, spreading over a bluff. From the headstones it looked as if childbirth and infant fevers had been the big killers. No medical assistance in the 1840s, or not at Port Essington. A lot of women and children had been left behind when the soldiers pulled out.

It was a melancholy place, and I was glad to leave it. Then I forgot about it, or thought I had. It came back when I was given a book written by a fellow with the odd name of Watkin Tench, a marine officer who came out to Australia with the First Fleet. I fell in love with Tench, as most of his readers do. He is a Boswell on the page: curious, ardent, gleefully self-mocking. He didnt fit my image of a stiff-lipped British imperialist at all. The visit to Port Essington had made me realise that the pastthose early settlements in Australiahad once been as real as the present, which is always an electrifying realisation. Before I quite knew what was happening I had started work on the remarkably accessible documentation for the early years of the British presence at Sydney Cove. Through those British sources I also met the beach nomads of Australia. My aim in what follows is to understand what happened between these un-like peoples when they met on the edge of a continent 20,000 kilometres from England.

The imperial adventure in Australia was played out by a very small cast. A handful of British observers are our main informants as to what happened between the races during Arthur Phillips governorship, which began in January 1788 and effectively ended with his return to England in December 1792. In 1796 his friend and secretary David Collins also went home. Nine years is a brief time span, but in my view much of what mattered most in shaping the tone and temper of whiteblack relations in this country happened during those first few years of contact.

Doing history teaches us to tolerate complexity, and to be alert to the shifting contexts of actions and experience; anthropology reminds those historians who still need to be reminded that high male politics isnt everything, and that other cultures manage to get along using accounts of the world we find bizarre, even perverse. Historians main occupational hazard is being culture-insensitive, anthropologists is insensitivity to temporal change. Both can be insensitive to the reciprocating dynamic between action and context. Together, however, they are formidable, and in my view offer the best chance of explaining what we humans do in any particular circumstance, and why we do it. In what follows I have tried to bring the two methods together in the analysis of a number of sequential episodes, interspersed with short explanatory essays when I think the reader might need to pause for breath.

Next page