Text Classics

was born Inga Vivienne Jewell in Geelong in 1934, the youngest of four children. She studied at the University of Melbourne, where she subsequently worked for a decade. Aged twenty, she married the philosopher John Clendinnen and they had two children.

Clendinnen moved to La Trobe University at the end of the 1960s and was a lecturer there for two decades. Her writing and research on the Aztecs and Maya of Mexico earned her a reputation as one of the worlds finest historians.

Her first book, Ambivalent Conquests, was published in 1987. Nearing the completion of her second, Aztecs: An Interpretation (1991), she was diagnosed with chronic liver disease.

In 1994, after a liver transplant, Clendinnen ceased teaching and her writing took new directions. Reading the Holocaust (1998) was a New York Times notable book. The next year she turned her attention to Australian history for the first time, presenting the fortieth annual Boyer Lectures, later published as True Stories. Tigers Eye (2000), a scintillating memoir of illness, won her a new readership.

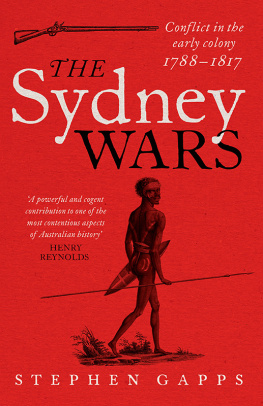

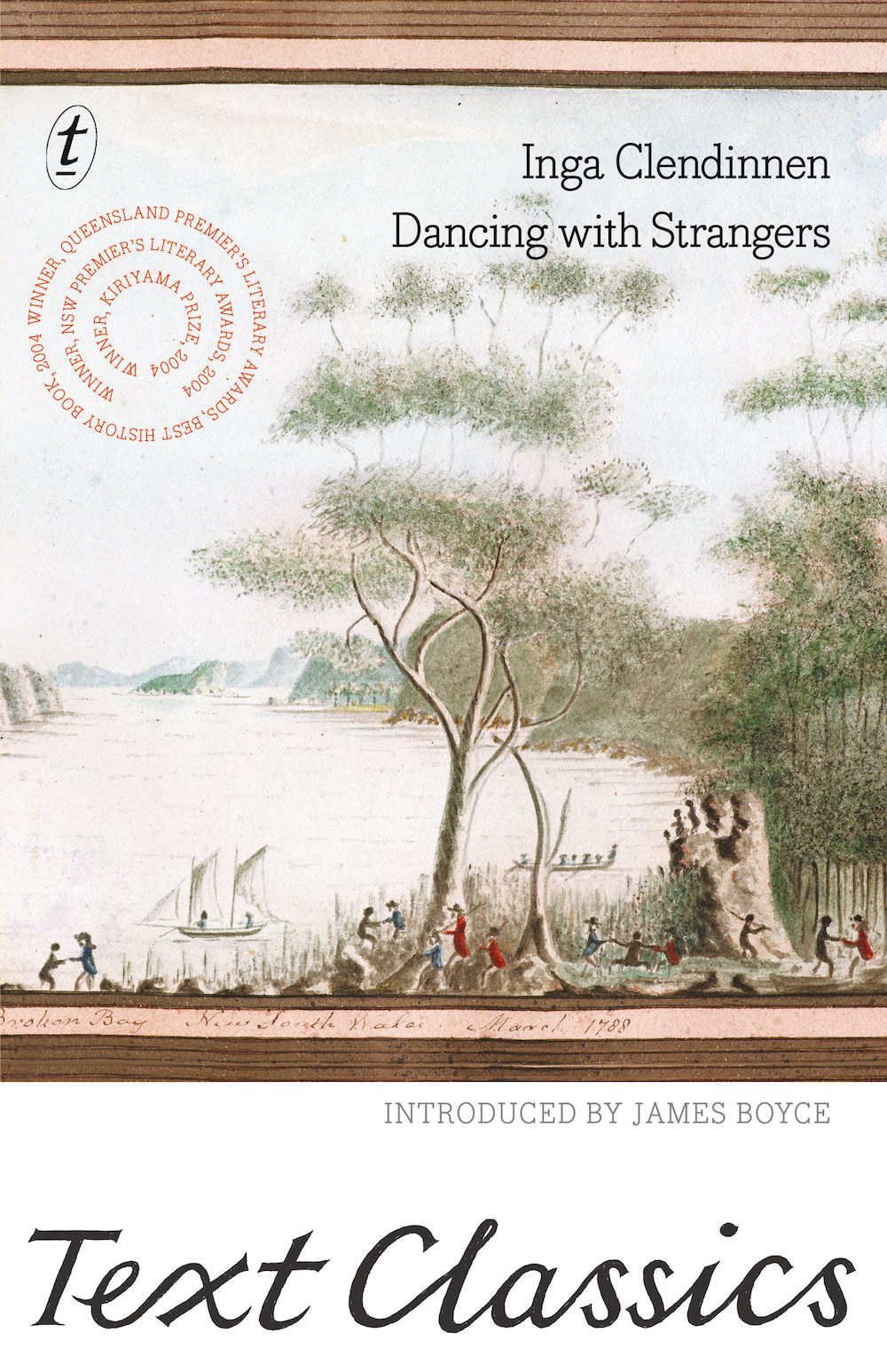

Dancing with Strangers (2003) brought more acclaim. Published at the height of the history wars, Clendinnens examination of the first contact between the British settlers and the Aboriginal people of Sydney Harbour in 1788 was characteristically sage and empathetic. David Malouf said she claimed for history the same power as poetry or fiction to enter the silences and make them speak. Peter Singer called her one of the countrys great public intellectuals.

In 2006 Inga Clendinnen was made an Officer of the Order of Australia. She was named co-winner of the Dan David Prize in 2016 and died later that year.

is the author of Losing Streak (2017), Born Bad (2014), 1835 (2011; winner of the Age Book of the Year Award) and Van Diemens Land (2008). He has a PhD from the University of Tasmania, where he is an honorary research associate of the School of Geography and Environmental Studies.

Ambivalent Conquests:

Maya and Spaniard in Yucatn, 15171570

Aztecs: An Interpretation

Reading the Holocaust

True Stories: History, Politics, Aboriginality

Tigers Eye: A Memoir

Agamemnons Kiss: Selected Essays

The Cost of Courage in Aztec Society:

Essays on Mesoamerican Society and Culture

CONTENTS

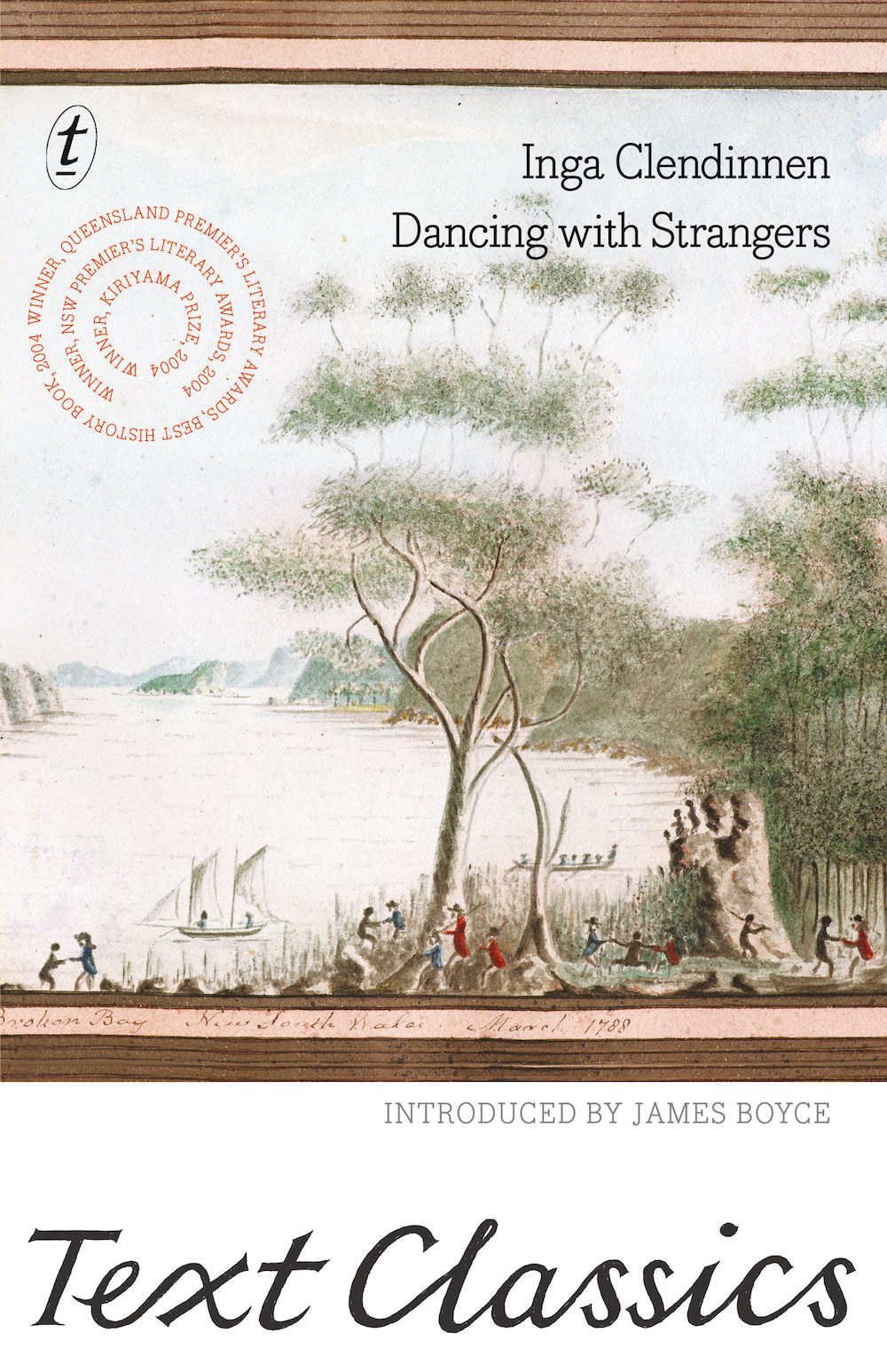

THE publication of Inga Clendinnens Dancing with Strangers in 2003 gave Australia what the country desperately needed for the new millennium: a founding story in which the human beings who encountered each other in 1788 could finally become part of the national imagination.

The French historian and political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville argued in Democracy in America that, just as the entire man is, so to speak, to be seen in the cradle of the child, nations too bear some mark of their origin. The circumstances that accompanied their birth and contributed to their development affected the whole term of their being. The truth of this observation was already self-evident by the time de Tocqueville visited America in the early 1830s. But what would this idea mean for a convict colony?

There are reasons to be grateful that Australia has lacked the national self-confidence conferred by a founding tale of pilgrim fathers making their home in a promised land under the protection of divine providence. A creation story centred on convicted criminals being exiled to an unfathomable, faraway country has undoubtedly made for a less crudely celebratory conquest of a continent. However, Australia has also been diminished by its circumscribed founding story. Would we collectively have so comprehensively forgotten Aboriginal people in law, culture and history if the nation had followed the United States lead and remembered with thanksgiving the indigenous people who helped the white settlers avoid starvation? What depth of meaning would be added to Australia Day barbeques if they reminded people of the cross-cultural campfire feasts of 1788?

Despite the newfound prominence of 26 January, what remains remarkable about the British settlement of Australia is how few consequential stories have been told about it. The cultural legacy of two hundred years of storytelling amounts to little more than a vague association between those early years and hungry convicts, incompetent soldiers, fanciful flag-raising, failed crops and a hostile environment. Because Aboriginal people hardly figured in these yarns (didnt the people living around Sydney just get smallpox and die?), even interested Australians have been left with a terra nullius of the imaginationfounding fathers devoid of a relationship with the land and its original inhabitants.

There are signs of change. A recognition that, from the Aboriginal perspective, Australia Day marks Invasion Day has taken hold. The historical scholarship in the 1970s and 1980s that challenged what the anthropologist W. E. H. Stanner called the Great Australian Silence brought to the fore what had been widely known in the nineteenth centurythat settlement sometimes meant a bloodbath. But if the debate about the past has sometimes been reductive, it is not the fault of the Australian historians who laboured from the mid-1980s to explain the complexity of the frontier. This scholarship on encounter, adaptation and resistance did not contradict the tragic story of violence and dispossession but instead humanised it.

The work of most academic historians is, however, little read, and at the time of the great reconciliation walk across Sydney Harbour Bridge in 2000 (replicated on other bridges across the nation), the past was widely thought of only as a problem to be overcome. The tendency to identify Aboriginal people exclusively as victims and the white settlers as all-powerful, immutable imperialists made for a rupture between the contemporary reconciliation project and history.

What was needed for the past to inform the present was an accessible founding story centred on real human beings: acting, responding, choosing, feeling, communicating, misunderstanding and deliberating according to the context of their times. It was in this cultural vacuumlonging might be a better wordthat one of Australias most eminent historians began to study her nations past.

Inga Clendinnen was a latecomer to Australian history. Raised in Geelong in the 1930s and 1940s, she had a long and distinguished academic career at Melbourne and La Trobe universities in Mesoamerican studies. After illness forced a premature retirement from her chosen field (there could be no more research trips to Mexico), Clendinnen became enthralled by the journals of George Augustus Robinson, the first Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Port Phillip District, which became Victoria. His words were weaved into her extraordinary memoir of hospitalisation, Tigers Eye (2000).

Robinson also appeared in Clendinnens 1999 Boyer Lectures, published as True Stories: History, Politics, Aboriginality, which explored accounts of encounters between indigenous Australians and those who came into their country. But it was Dancing with Strangers that would lay the historical foundation for reconciliation by transforming not just our understanding of the cross-cultural meetings that occurred but their meaning.

Dancing with Strangers is based almost entirely on early journals, letters and other first-hand accounts of the founding years in the colony of New South Wales, beginning with the moment when the new arrivals from Britain had a friendly meeting with the Australians living around Sydney Harbour, dancing, hair-combing and singing. The book is not intended to be a comprehensive history of first settlement: there is little in it on the imperial or global context, the penal system or the reasons for the founding of the new colony. Even the Colonial Office in London, which drove the enterprise, is not a big player in this drama. Rather, through a direct engagement with the sources written by the people who were there, the book gives us an insiders account of the landmark encounter. The conversation, curiosity and cohabitation that characterised early Port Jackson (and many later frontiers) never excluded violence, dispossession and disease. The seizure of land and resources was the very purpose of the colonial project and this fact, rather than misunderstanding or malevolence, was the primary cause of the unfolding tragedy.

Next page