1835

1835

THE FOUNDING OF MELBOURNE &

THE CONQUEST OF AUSTRALIA

James Boyce

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Media Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

email: enquiries@blackincbooks.com

http://www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright James Boyce 2013

First published 2011

Reprinted 2012

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

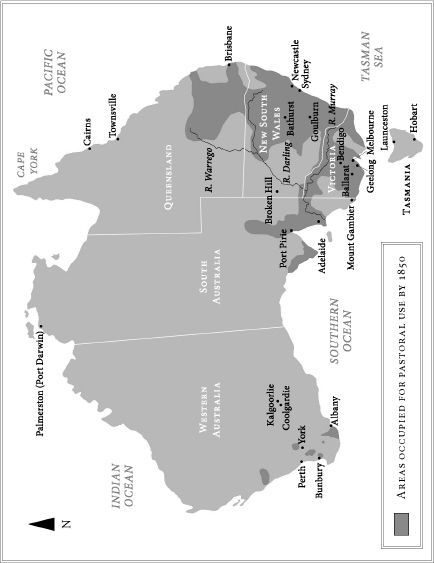

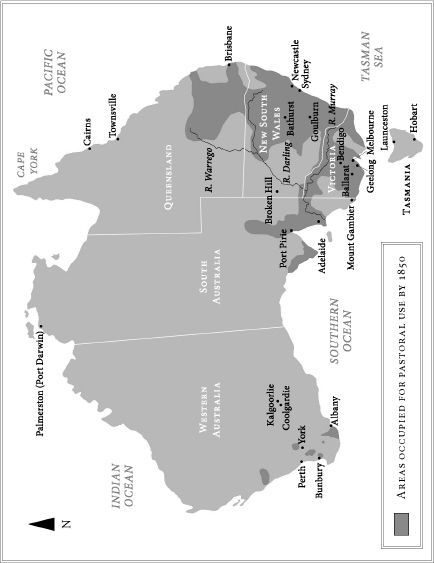

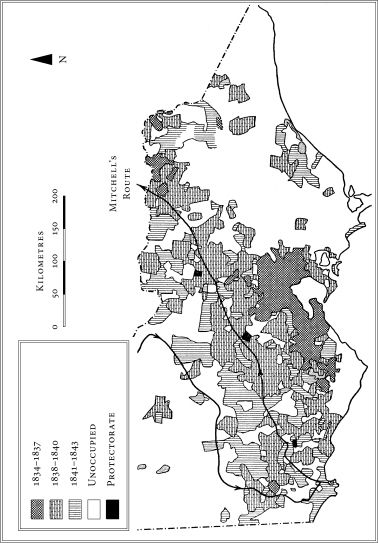

Map of the is adapted from The Oxford History of the British Empire, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of material in this book.

However, where an omission has occurred, the publisher will gladly include acknowledgment in any future edition.

ISBN for eBook edition: 9781921870958

ISBN for print edition: 9781863956000 (pbk.)

Cover design by Peter Long

Cover image: Detail of The first settlers discover Buckley, Frederick William Woodhouse, 1861. State Library of Victoria

To Julie Pender and Terry Burke,

heroes of Port Phillip

CONTENTS

One cannot complain of what cannot be otherwise.

ISAIAH BERLIN, 1954

IN 1835 AN ILLEGAL SQUATTER CAMP was established on the banks of the Yarra River. This brazen act would shape the history of Australia as much as would the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, because it was now that the continent was fully opened to conquest. No more was settlement to be restricted to defined boundaries: within twelve months the British government would allow settlers to go where they pleased.

Melbournes birth, not Sydneys settlement, signalled the emergence of European control over Australia. Britons had, of course, never been wholly confined within the official limits of location (which by 1835 extended about 120 miles inland from Sydney),1 but it was only after the abandonment of the long-established policy of concentrated settlement that exclusive territorial claims beyond defined borders were made, perfect sovereignty over Aboriginal country was asserted, and the continental land rush began.

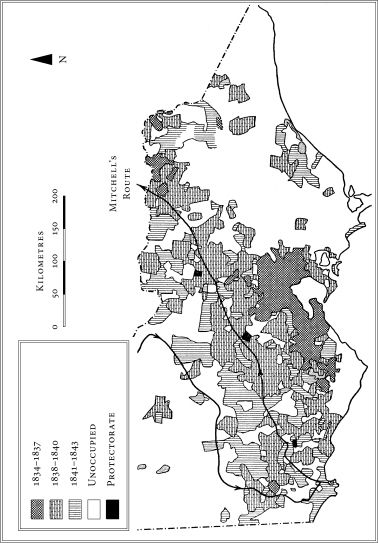

Between 1835 and 1838 alone, more land and more people were conquered than in the preceding half-century. By the end of the 1840s, squatters had seized nearly twenty million hectares of the most productive and best-watered Aboriginal homelands, comprising most of the grasslands in what are now Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and southern Queensland. It was one of the fastest land occupations in the history of empires.2 In little more than a decade, the continental pinpricks which represented the totality of British occupation in 1835 became a sea of red.

The catalyst for this momentous change in settlement policy was the founding of Melbourne, the only major Australian city established without government sanction. The movement of men and sheep across Bass Strait from Van Diemens Land, as Tasmania was then known, was a private and highly speculative investment. No one was in any doubt that it was also trespass. Consequently, the pioneers principal challenge was not to subdue the physical environment this was benign grassland country but to achieve a change in law and policy.

The principal obstacle to achieving a political decision favourable to the squatters cause was the Aborigines. After the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833, energised evangelical reformers had turned their attention to the plight of the empires native peoples. In 1835 a Whig government led by Lord Melbourne came to power, and evangelical activism permeated the highest offices of the land.

One of the most important questions of Australian history is why, at the apex of imperial concern for the rights of indigenous people, an evangelical Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, responded as he did to the challenge posed by the ambitious property speculators of Van Diemens Land. Why did he decide to end the policy of restricted settlement and allow the sheep barons to send their men and flocks anywhere they chose? How did he and other evangelical political leaders of London (and indeed Sydney and Hobart) come to promote a legal and policy change that saw colonisation degenerate into a frenzied land grab?

To understand how the floodgates were opened to the continents vast pastures, it is necessary to travel far from the Port Phillip district, as Victoria was then called. In 1835, in Hobart, Sydney and London, the inter-related questions of the Aborigines and colonisation were being considered by bureaucrats, politicians and activists. It will be seen that the squatters themselves were far from passive agents: through their famous treaty with the Aborigines and their careful lobbying, conducted all the way from remote grasslands to the offices of Westminster, the well-connected gentlemen of Van Diemens Land pursued their profitable cause. The squatters did not win private title, but the open access conceded by the government had more dramatic consequences than even their ambitious scheming could have anticipated. The tsunami generated by the change in government policy in 183536 was such that almost every resident of Australia, black and white, was swept up in its tide.

After the founding of Melbourne, colonial ambition, regulation and law finally came into alignment. So strong was the new consensus (despite endless dispute over detail) that the right of settlers to live where they chose soon became taken for granted. What had been one position (albeit the dominant local one) in a complex debate was now taken to be common sense. Indeed, the ridicule of the previous policy of concentrated and restricted settlement was so effective and long-lasting that the most important question of all seems to have disappeared: could it have been different? Did the continent have to be colonised this way?

I set out to write a book about the founding of Melbourne. Only full immersion in the Yarras murky waters led me to understand that the policy turmoil which followed the establishment of a squatters camp in 1835 had a significance far beyond the baptism of a great city. In this place, at this time, Australia was born.

ABOUT FORTY MILLION YEARS AGO volcanoes began erupting in what is now Victoria. As Tim Flannery recounts, in time the resulting basalt rock would break down to form the largest area of rich soils in Australia [and] one of the continents most productive regions. The lava flow and the basalt plains were concentrated in the west, with the Yarra River sitting astride the soil divide.1 Under Aboriginal land management, through what has become known as fire-stick farming,2 much of the country to the west and north of Melbourne became open grassland. It was these hunting grounds that would eventually be the focus of British ambitions, although equally characteristic of the lower Yarra were the oftforgotten swamps.

Next page