Kate Masur - Until Justice Be Done

Here you can read online Kate Masur - Until Justice Be Done full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: W. W. Norton & Company, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Until Justice Be Done

- Author:

- Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Until Justice Be Done: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Until Justice Be Done" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Until Justice Be Done — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Until Justice Be Done" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

UNTIL

JUSTICE

BE DONE

Americas First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction

KATE MASUR

FOR PETER

IN THE SUMMER OF 1843, a group of African American activists in Ohioamong them ministers, teachers, and laborersconvened in the state capital of Columbus with the primary goal of fighting the states racist laws. Since the first decade of the nineteenth century, the laws of this free state had construed African Americans as a separate and threatening class of people. Ohio laws prohibited Black people from testifying in cases involving whites. The laws required African Americans to register with local authorities, which included paying fees and finding two landowners to promise that they would not become dependent on public resources. These discriminatory laws, which abridged what many considered basic civil rights, were commonly known as the black laws.

African American men were not permitted to vote in Ohio, despite a declaration in the 1803 Ohio Constitution that all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable rights. The constitution reserved the franchise to white men, leaving Ohios Black residents, just one percent of the total population, at the mercy of the white majority that elected the legislators who wrote the laws. If African Americans wanted state laws to change, they needed to persuade white Ohioans that their cause was just.

The result of the 1843 meeting was an address to the citizens of Ohio, written by four men, including A. M. Sumner, a Tennessee-born barber, and George Vashon, the first African American graduate of Oberlin College. The address called on white Ohioans to recognize the injustice of their laws, insisting that the governments policy toward them was utterly at variance with the promises of the Declaration of Independence. State law should constitute the bulwark of our liberties, the committee declared, and yet Ohio law was employed as the instrument to hunt us down to degradation and shame. The group implored white Ohioans to see the world through their eyes. Their own state denied their fundamental rights, while just to the south, the slave states of Virginia and Kentucky were even worse. Is life secure, is liberty inviolate, is the pursuit of happiness left open to us, they asked, when the hand of the ruffians can be raised against our existence with impunity; when the legislatures of adjoining states hesitate not to enact laws which militate against freedom, and the laws of our own state may be construed to deprive us of the enjoyment of liberty[?]

Would the Ohio legislature allow the racist laws to remain? Or would voters change course and embrace the principle of racial equality before the law? Across the twenty-six states that then formed the United States, state legislatures enjoyed enormous authority, and laws that singled out Black residents for discriminatory treatment were widely accepted. Writing in 1846, a political season in which repeal of the Ohio black laws took center stage, the Cincinnati Enquirer, a Democratic newspaper, defended the laws with the argument that they were among the many kinds of regulations which may be designed for the protection and peace of the actual settlers of a State. States were entitled to adopt policies that guarded residents against threats of fire, disease, crime, and other kinds of disorder. If the Ohio legislature believed that African Americans threatened the public peace, the Enquirer contended, it was within its rights to impose special regulations designed to discourage them from entering its jurisdiction and to hem them in once they arrived.

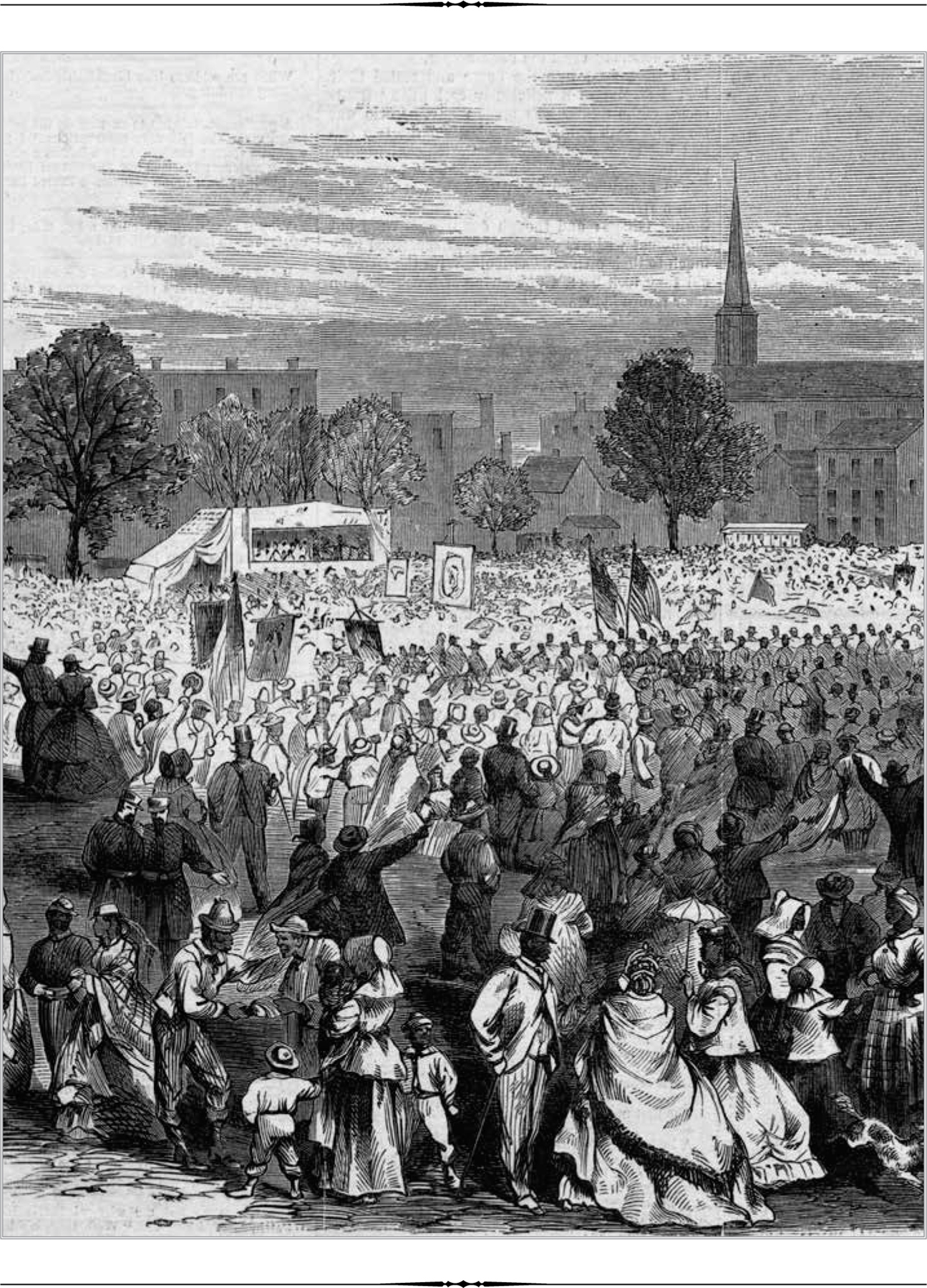

The push to repeal the Ohio black laws was one revealing episode in a sustained struggle over race and equality that stretched from the nations founding until the Civil War and beyond. Across the free states, activists forcefully insisted that laws that made explicit race-based distinctions had no place in American life. The movement began in the era of the American Revolution, when demands for citizenship and equal rights for Black Americans were part of broader revolutionary currents that emphasized the dignity and fundamental equality of all humanity. Advocates persisted in the period of retrenchment that followed, as states increasingly adopted laws that construed free Black people as an unwanted class. They made their case in antislavery societies, in the press, and in party politics, where they eventually found a home in the Republican Party. During the Civil War and Reconstruction, Republican majorities in Congress pursued the agenda of racial equality before the law that earlier generations of activists had established. Empowered by the crisis, they passed the nations first federal civil rights law and the Fourteenth Amendment, which forever changed how Americans understood individual rights and their protection.

This sustained struggle against racist laws was Americas first civil rights movement. We have often failed to see this movement because our focus was elsewhereon the origins of the sectional crisis, the great preCivil War debate over slavery, or the history of northern Black communities themselves. What we have missed was a struggle for racial equality in civil rights that spanned the first eight decades of the nations history, a movement that traveled from the margins of American politics to the center and ended up transforming the US Constitution. The movement encompassed pastors, journalists, lawyers, politicians, and countless ordinary citizens who demanded that the nations white majority reject racist laws and join the struggle for a better, more just society. Activists mainly advanced their arguments at the state level, where most individual rights were defined and enforced. When they could find a constitutional rationale to do so, they also addressed the federal government, in Congress and in the courts. They pressed new ideas about citizenship, individual rights, and the proper scope of state power, and their arguments informed the remarkable congressional debates of the 1860s.

The movement described in this book was a coalition that encompassed people with a wide array of views. African Americans were at the forefront of the activism and conceived racial equality most expansively. For Black people, the urgency was greater than for whites, and so was the danger. It was their children who were denied education, their property that could not be defended in court if they could not testify, and their brothers who might end up in a southern jail while pursuing their livelihoods as sailors. In the decades after the American Revolution, African Americans in the free states developed activist networks that spanned cities and regions. In newspapers such as New York Citys

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Until Justice Be Done»

Look at similar books to Until Justice Be Done. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Until Justice Be Done and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.