Peter Cole - Ben Fletcher

Here you can read online Peter Cole - Ben Fletcher full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Independent Publishers Group, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Ben Fletcher

- Author:

- Publisher:Independent Publishers Group

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ben Fletcher: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Ben Fletcher" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Peter Cole: author's other books

Who wrote Ben Fletcher? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Ben Fletcher — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Ben Fletcher" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

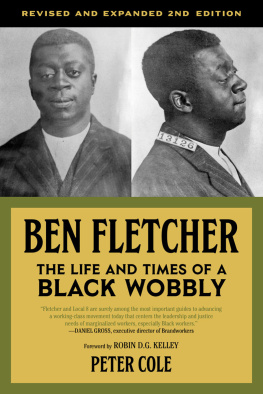

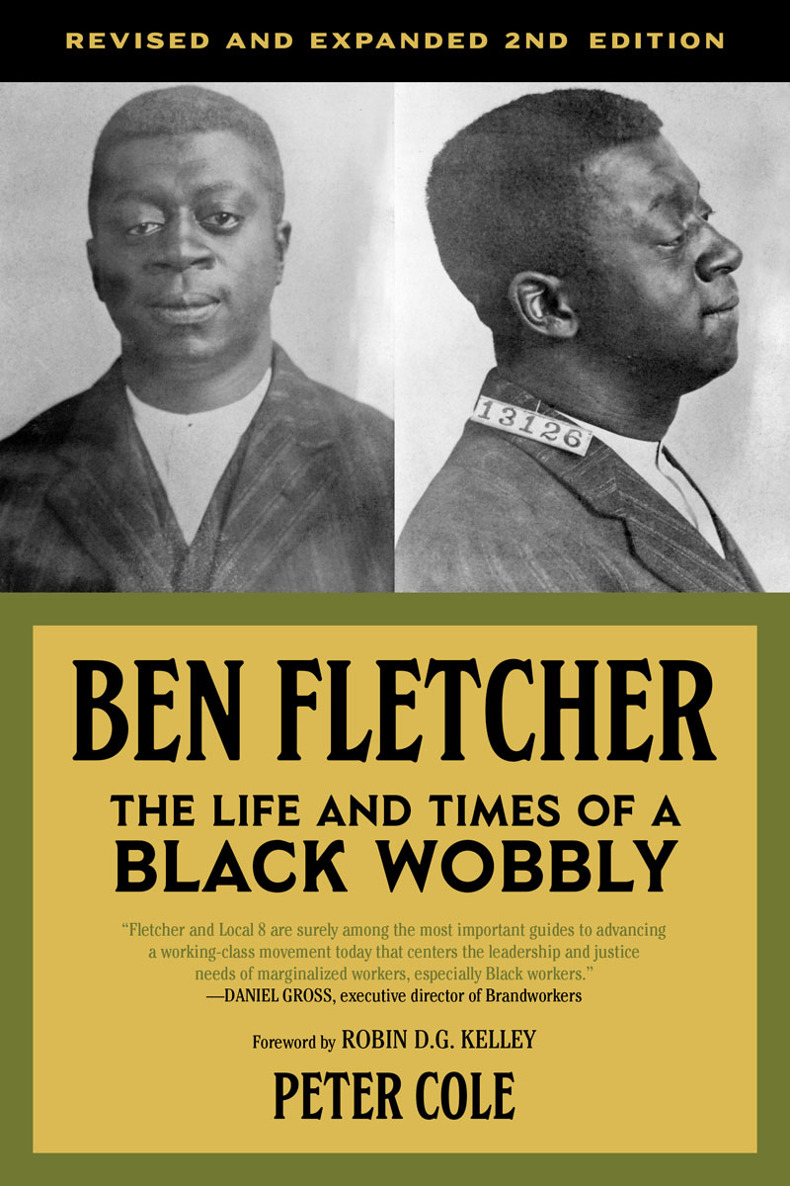

Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly, Second Edition

Peter Cole

This edition 2021 PM Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-62963-832-4 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-62963-862-1 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-62963-848-5 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020934738

Cover by John Yates / www.stealworks.com

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA.

Robin D.G. Kelley

Fletcher is the real type of Southern Nigger Agitator with no education, poor grammar. He is about 5 ft. 9 in. in height weighs 185 lbs.; and is reputed by the police as a bad man or a gun fighter. He did not display any of that to agent.

Report by Agent Henry M. Bowen, FBI, Boston, July 4, 1917

Rereading Peter Coles marvelous Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly amid a global pandemic has been something of a revelation. Of course, sheltering in place in order to reduce community spread of the COVID-19 virus is a far cry from the kind of confinement Ben Fletcher experienced in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary or what millions of imprisoned souls currently endurecaged men and women unable to escape the coronavirus and its potentially lethal consequences. But, truth be told, my epiphany about Fletchers life and significance derived not from some lofty reflections on the meaning of freedom from a place of confinement. The real source was Hollywood.

Like everyone else privileged enough to shelter in homes with internet and cable access, between Zoom talks, reading, writing, cooking, and cleaning, we watched TV. In honor of May Day, I streamed Reds, Warren Beattys three-hour masterwork about the Russian Revolution told through the romance of John Reed and Louise Bryant. I hadnt seen it since its theatrical release, which would have been the early part of 1982. A sophomore in college and diehard Marxist who had spent the previous summer reading the first two volumes of Capital and all three volumes of Lenin: Selected Works, I vividly recall tearing up as Reed and Bryant joined the throngs of workers marching down the streets of Petrograd toward the Winter Palace, singing the Internationale in Russian. But seeing it again after all of these years, I suddenly remembered why I found the film unsettling. For one thing, the radical Reed came across at times as a xenophobe. In one scene, Reed argued against uniting his Communist Labor Party with the rival Communist Party of America led by the Italian-born Marxist Louis C. Fraina because the latter wasnt truly American.

Reed: We cant merge with [Louis] Fraina. We cant deal with him on membership eligibility. He wouldnt accept half of our people. The man is gonna do nothing but alienate himself from any potential broad base of support. Hes sociologically isolated, programmatically hes impossible to deal with

Bryant: You mean hes a foreigner?

Reed: Dont do that, Louise.

Bryant: Six months ago, you were friends.

Reed: These people can barely speak English. They dont even want to be integrated into American life.

Even more troubling was the films thorough whitewashing of the Left. Here was a considerable slice of American Communist history without Negroes or even a Negro Question. One would never know from the film that John Reed was the first American to address the Communist International (Comintern) on The Negro Question in America. Delivered on July 25, 1920, just three months before his untimely death, his speech excoriated US racism, condemned lynching and disfranchisement, and heralded a new revolutionary movement among black workers and intellectuals such as A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, editors of the socialist-leaning Messenger magazine. Yet, while urging Communists to support black struggles for social and political equality, he argued that their main task should be to organize Negroes in the same unions as the whites. This is the best and quickest way to root out racial prejudice and awaken class solidarity. The IWW, he insisted, had been doing this all along.

In fact, Benjamin Harrison Fletcher should have shown up in Reds, and not just in cameo. Reed first met Fletcher in 1910, and like everyone in the IWWs circle, came to regard him as one of the most talented organizers the Wobblies ever produced. Even those hostile to the Wobblies acknowledged Fletchers venerated status among American labor leaders. The Messenger dubbed him the most prominent Negro Labor Leader in America. A target of the postWorld War I Red Scare, Fletcher also became one of the most prominent black political prisoners in the countrysecond only to Marcus Garvey. Indeed, he was the only African American among the 101 Wobblies convicted of violating the 1917 Espionage Act, for which he served two and a half years in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. Even after his death in 1949, long after the heyday of the IWW and his leadership of the Marine Transport Workers Union, Fletcher was still a widely respected figure in the labor movement. A fairly conservative black-owned newspaper, the Atlanta Daily World, ran a glowing obituary calling Fletcher one of the most brilliant Negroes ever associated with a leftist organization and highly respected for his scholastic ability and his oratorical efforts. The authors point that Fletcher was jailed because mass hysteria swept the country and new laws, Criminal syndicalism made its appearance as a weapon to prosecute supposed subversives was not lost on readers living through a new and more virulent Red Scare.

But by the time Reds hit the big screen, the name Ben Fletcher had faded into obscurity. In fact, it was precisely the whiteness of Reds that led me to books such as Philip S. Foners American Socialism and Black Americans, where that I first encountered Ben Fletcher. I found traces of him in Sterling Spero and Abram Harriss classic 1931 text, The Black Worker, in Robert Allens Reluctant Reformers, in Melvin Dubofskys massive history of the IWW, We Shall Be All, and obscure history journals. But even these excellent sources could not fully capture his complicated experiences as an independent black socialist labor leader, the breadth of his intellect and strategic brilliance, his triumphs and disappointments, not to mention his razor-sharp wit and wicked sense of humor.

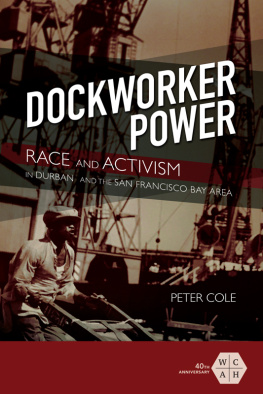

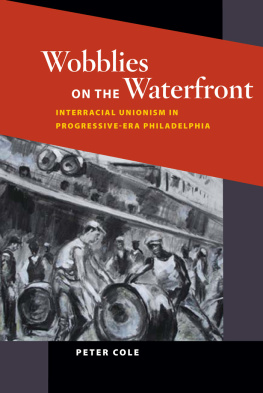

That all changed in 2007, when a young historian named Peter Cole published the first edition of Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly with Charles H. Kerr, the iconoclastic publishing house then run by the late Franklin Rosemont and Penelope Rosemont. It was soon followed by his magnificent monograph Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia (University of Illinois Press, 2007), which not only provided the most thorough account of Fletchers life but also placed him squarely at the center of dockworker organizing in the early twentieth century. And that meant reckoning with the dynamics of race and class, not to mention the potentialities and limits of direct action versus bread-and-butter unionism in an interracial but predominantly black labor movement. Fleshing out Ben Fletcher unsettled not only US labor history but also histories of American radicalism and Black Studies. We learn that Fletcher was more than a Black Wobbly. He exemplified the New Negro of the postWorld War I era but was never included among the eras celebrated intellectuals, artists, and activists despite having been lionized in the pages of the

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Ben Fletcher»

Look at similar books to Ben Fletcher. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Ben Fletcher and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.