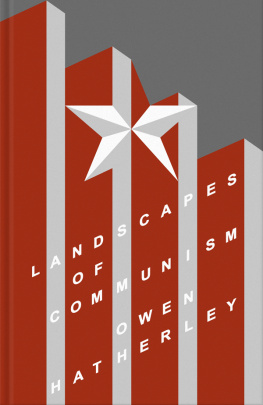

2015 by Owen Hatherley

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane, Penguin Random House UK, 2015

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2016

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Hatherley, Owen, author.

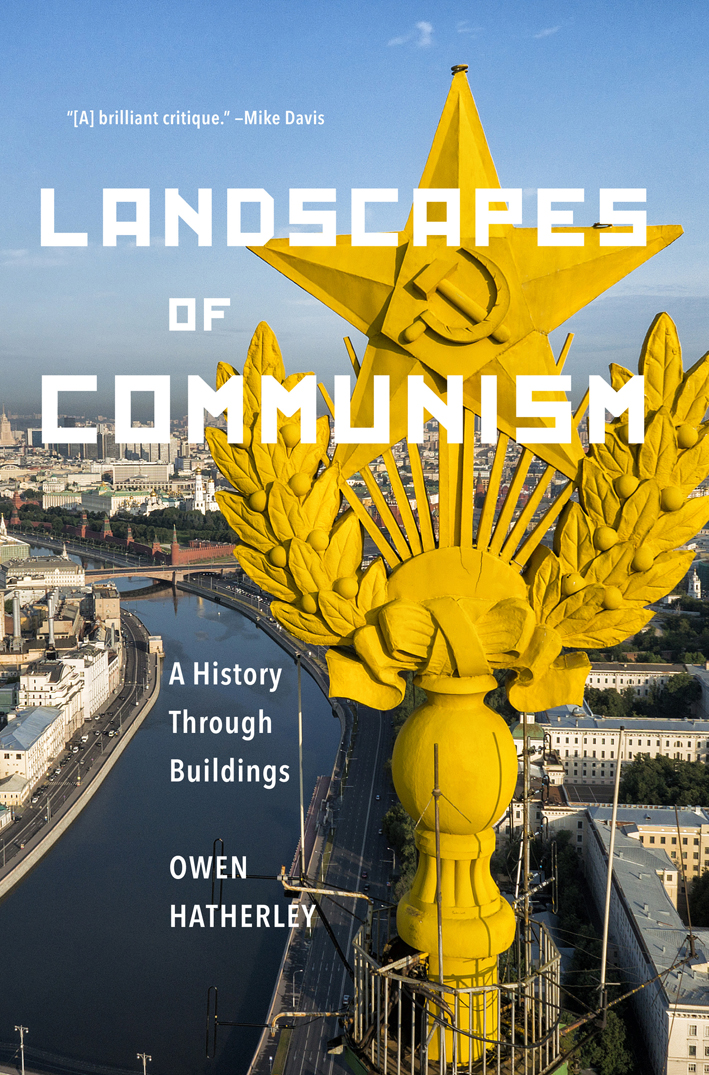

Landscapes of communism: a history through buildings / Owen Hatherley.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62097-189-5 (e-book)

1. Communism and architectureEurope, EasternHistory. I. Title.

HX520.H38 2016

720.947'09045dc23 2015032819

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by Jouve (UK)

This book was set in Sabon MT Pro

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Dla Agatki, z mioci Socjalistyczna Stolica Miastem Kadego Obywatela Robotnika, Chopa i Pracujcego Inteligenta!

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

... it was inappropriate to build it, and it would also be inappropriate to demolish it

Deng Xiaoping on Maos Mausoleum

We intend to tell you what socialism is. But first we must tell you what it is not and our views on this matter were once very different from what they are at present. Here, then, is what socialism is not.

... a society where ten people live in one room a state that possesses colonies a state that produces superb jet planes and lousy shoes one isolated country, a group of underdeveloped countries a state that employs nationalist slogans a state which currently exists a state where city maps are state secrets a state where history is in the service of politics...

That was the first part. But now listen attentively, for I will tell you what socialism is. Well, socialism is a really wonderful thing.

Leszek Koakowski, What is Socialism? (1956)

COMMUNISTS OF HAMPSHIRE

For several decades, my grandparents were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Im not now going to regale you with stories about their strange habits and political delusions, or denounce their decision from the lofty heights of hindsight. Im not going to retrospectively tell them off. Instead, Im going to describe where they lived, and what this said about them and what they believed. For the last thirty or so years of their lives they lived in a small semidetached early-twentieth-century house in Bishopstoke, a suburb not far from the Eastleigh Railway Works, on the outskirts of Southampton. From the outside the house was nondescript; it was what was inside that made this noticeably different from any other of these houses for railway clerks. A framed print of Salisbury Cathedral was on the living-room wall, as were several paintings of northern rural scenes. A polished wood and glass cabinet displayed hardback sets of Bernard Shaw, Shelley, Dickens, and a complete bound set of the CPGBs Labour Monthly from 1945 to 1951. The books on the other shelves were divided between childrens books, books on ornithology, and political books The Socialist Sixth of the World, New China: Friend or Foe?, the Marxist literary critic and Spanish Civil War martyr Christopher Caudwell, the Stalinist and biologist J. B. S. Haldane which all seemed to end in 1956, not, I think, because of the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution or the Secret Speech in which Khrushchev revealed (some of) the crimes of Stalin, but because that was the year they had their first child, at which point they dropped out of active communist politics.

You probably wouldnt have noticed any of this if you were to visit, but you would definitely have noticed the huge plate glass window at the edge of the living room, giving a complete view of the garden. They would usually sit here and watch for birds. The garden itself had been transformed from a small suburban patch into something more wild. A green path ran between two dense thickets of tall, bright plants, with paths running through them and a bench placed somewhere unexpected in the middle; at the end of it was a shed, which we were discouraged from visiting, as Grandad used this as a quiet place, away from children and their din. Here, heaps of compost and tangles of wisteria gave way almost imperceptibly to an overgrown alleyway, which led to a churchyard and a huge, slate-grey Victorian church, whose clang you could hear from inside the living room. These, Im afraid, are the people I think of when I think of communists, and for most of my life, this entirely private place they created was the most extensive I had experienced that had been made, created, tended, by communists.

So Ive often wondered, in the last few years, what they would have made of certain other spaces that had been created by communists, in those countries where they were the unquestioned ruling power rather than a small party that was a tiny minority just about everywhere outside of South Wales and Central Scotland (both so far away from Southampton they might as well have been abroad). I wondered what they would have made of ekin, on the outskirts of Vilnius, Lithuania, where grey prefabricated towers with balconies at unlikely angles are cantilevered over vast, usually empty public spaces. Would they have liked it? Had they lived there, would they have tried to make gardens in those in-between spaces? Would they have been impressed by the technology and the extent of the amenities? I wondered what they would think of MDM, the centrepiece of rebuilt Warsaw, where absolutely immense neo-Renaissance blocks are decorated with giant reliefs of musclebound workers. There was no imagery like that in their books or on their walls. Would they have identified with it? Would it have made them feel powerful, or would they have felt as if power was aiming to intimidate and crush them? What would they have made of the Moscow Metro, with its staggeringly opulent gilded halls? Would they have considered all this grandiose display something that was best for a distant, recently feudal country, or would they have wanted the same at home? They never visited the communist-ruled states of Europe and Asia, so I dont know, and I never got the chance to ask. They would almost certainly have found the homes there worse than a semi on the outskirts of Eastleigh, but would they have contrasted them favourably, at least, to the places they came from to the slums of Portsmouth, or rural Northumbria, respectively? Im not sure, but of all the communist-built places I have seen in the last few years, I can only think of a handful where I can be absolutely sure they would have found something to their satisfaction the old towns of Warsaw, Gdask, and St Petersburg, which were meticulously reconstructed after the war. I suspect theyd have preferred them to the starker lines of rebuilt Southampton or Portsmouth, but they might have reflected on the fact that these were mere replicas of cities from a pre-revolutionary past, not visions of the future.