Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books paperback original 2022

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright Owen Hatherley 2022

Owen Hatherley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

ISBN: 9781914420863

Ebook ISBN: 9781914420870

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd

We, the last men of the earth and the last of the free, have been shielded till today by the very remoteness of our rumoured land. But now the boundary of Britannia is exposed, and everything unknown is valued all the more. Beyond us lies no other nation, nothing but waves and rocks and Romans, more deadly still than they, whose arrogance no submission or moderation can elude. Brigands of the world, after exhausting the land by their wholesale plunder they now ransack the sea. The wealth of an enemy excites their greed, his poverty their lust for power. Neither East nor West has served to glut their maw. Only they, of all on earth, long for the poor with as keen a desire as they do the rich. Robbery, butchery, rapine, these the liars call empire: they create desolation and call it peace.

Calgacus the Caledonian, in Tacitus, Agricola (98 AD)

Colonies do not cease to be colonies because they are independent.

Benjamin Disraeli (1863)

Opportunities are available in all walks of life in Australia

Australia, no class distinctions

Australia, no drug addictions

Nobodys got a chip on their shoulder

Everyone walks around with a perpetual

smile across their face

The Kinks, Australia, from

Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) (1969)

CONTENTS

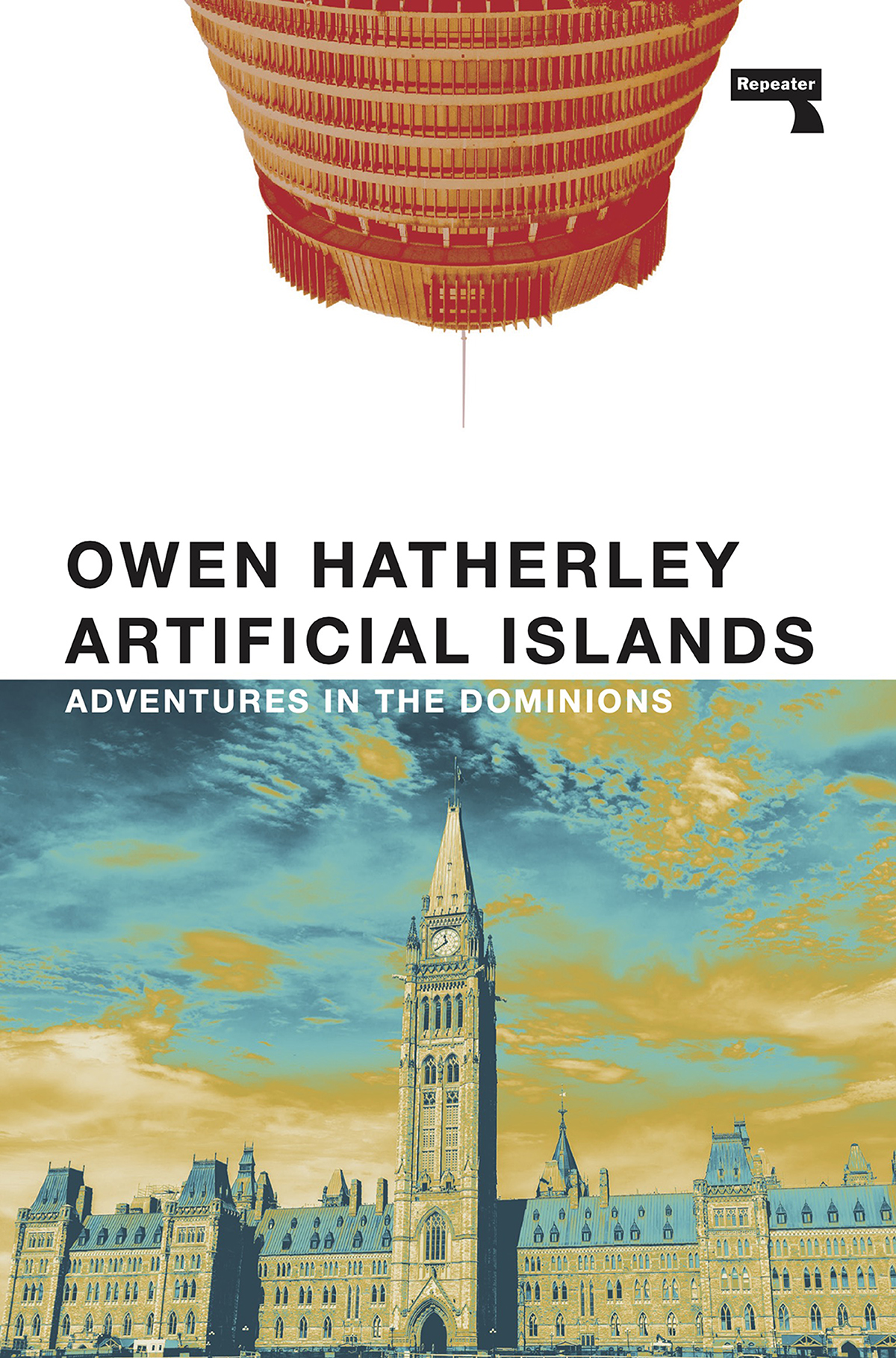

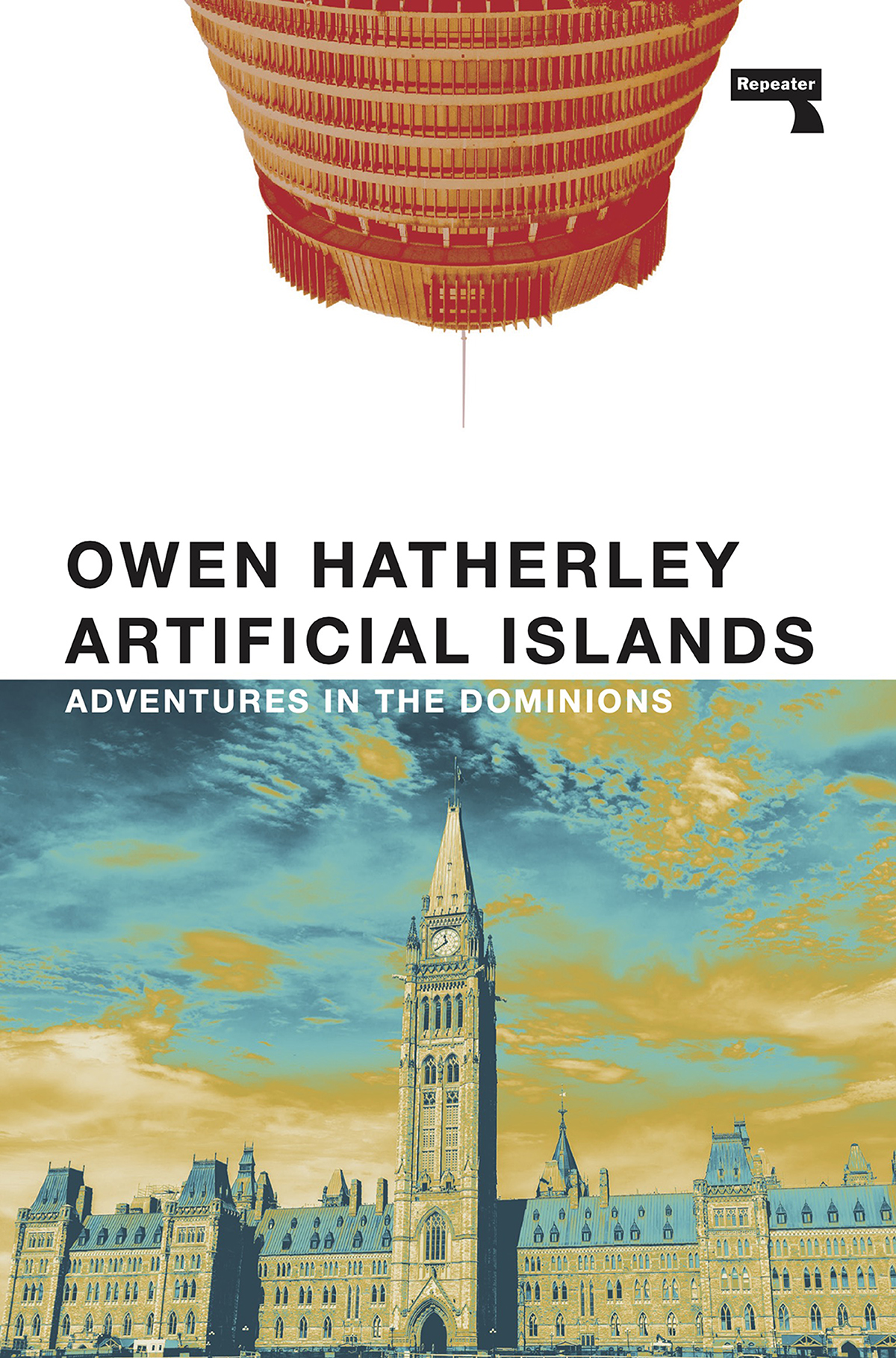

INTRODUCTION: THE VIEW FROM THE ISLAND

Isle of Wight, Heart of Darkness

An essential madness of British Imperialism is its sheer success in creating replicated versions of the home environment in the most unlikely places. An apparently parochial way of building towns, cathedrals or houses reappeared in a very different corner of the Earth, and architectural styles that might otherwise be firmly associated with Surrey, the West Midlands or central Scotland were faithfully reproduced in the places where British people aimed to build a replica of their society on the waste theyd made of somebody elses in the deserts of Australia and the grasslands of South Africa, in the tundra of Canada, in the volcanic hills of New Zealand. One building in particular was replicated many times in the second half of the nineteenth century, and youll find it on a separate island to the south of the main island of Great Britain: Osborne House, Isle of Wight.

The island, as those of us from the Solent region refer to it, is a place that thrived at the height of the Empire and was then left adrift, for a time, by a change in the availability and speed of travel, and by a change in the alliances of the British state. In the 1960s, large numbers of working- and middle-class British people started travelling to continental Europe every summer, the first time they had done so since being forced to by conscription. This had serious consequences for a series of damp coastal resorts along the Irish Sea, the North Sea and the Atlantic, from the palm trees of Rothesay to the picture palaces of Blackpool to the carefully faked villages of the Isle of Wight itself. A guide to the island from that decade, however, makes a case for the continued importance of its own corner of that chain of resorts:

The majority of people taking a holiday want a complete change. The Continent offers much but a large number of holiday makers hesitate going to foreign places, where they feel they will be at a disadvantage coping with strange languages and currency. The Isle of Wight solves this problem admirably. Not too far away, the thirty minute sea trip provides the stimulus of going abroad and is one of its attractions.

You could travel on the seas and arrive in the same place only very slightly different. Sunnier, with more trees, more space. Everyone speaks English, but the sun is shining, and there is tropical vegetation in the chines of the Undercliff.

In 2020 and 2021, this went from being a completely ridiculous idea to a rather attractive one, if you were stuck in a British city in a situation where it was generally, with occasional brief intermissions, impossible to travel abroad. As numerous historians and novelists know well, the Island offers a condensed, refracted England, with fragments of each of its landscapes crammed into its tiny space. Similarly, its towns take on the identity of the place they face towards Ryde a punchy miniature Portsmouth, Newport a vague and ugly Southampton, and lush Victorian resorts like Shanklin and Ventnor resembling Normandy if governed by the Conservative and Unionist Party. It is England, but also more England than England.

Thats roughly how it came to be that in July 2021 I spent my fortieth birthday visiting a private house, completed in 1851 by the developer Thomas Cubitt, who was then building much of what is now inner London. Osborne House stands near Cowes at the northern tip of the Isle of Wight, and was built as a summer house for Queen Victoria and Albert, the Prince Consort, who had a hand in designing it. In the histories of royal palaces, it is generally described as a mere house, and a sign of this peculiarly bourgeois, upstanding constitutional monarchys modest tastes and empathy with its subjects they even used the same builder as an ordinary terrace in Pimlico. But it is of course a palace, with so much space that an entire naval college was for a time run from here until it was finally taken over by English Heritage. However you can just about see what they mean. This is not Versailles or Peterhof; no absolute monarch, no Sun King, would be satisfied with this place. The scale is that of a medium-sized late-nineteenth-century Board school. There is no symmetry, and there is no triumphal approach. It is as informal as the home of the empress of an Empire on which the sun never set could possibly be.

It begins as a typical large Italianate house of the period, flat-roofed, stuccoed and slightly stiff an artefact of the German princes stolid continental good taste. Inside, this taste, with its history paintings, marble casts of Greek and Roman statuary, fights it out with Victoria and her childrens love of kitsch, displayed through dozens of paintings of their dogs, and seen at its most grotesque in an entire room where the furniture, picture frames and much else have been crafted from antlers. It is high-tech, too, with all manner of lifts, dumbwaiters and then-novel electrical devices to keep the royal family in comfort. Outside are Palladian windows, two campaniles and a grand terrace of statues and fountains, planted with the semi-tropical flowers and plants that thrive in the Islands microclimate, descending to what you might assume would be a grand path towards the Solent. But that would be to compromise the familys much-cherished privacy. The house directly faces the city of Portsmouth; you can see the power stations and oil refineries of Southampton Water, too. But while

Next page