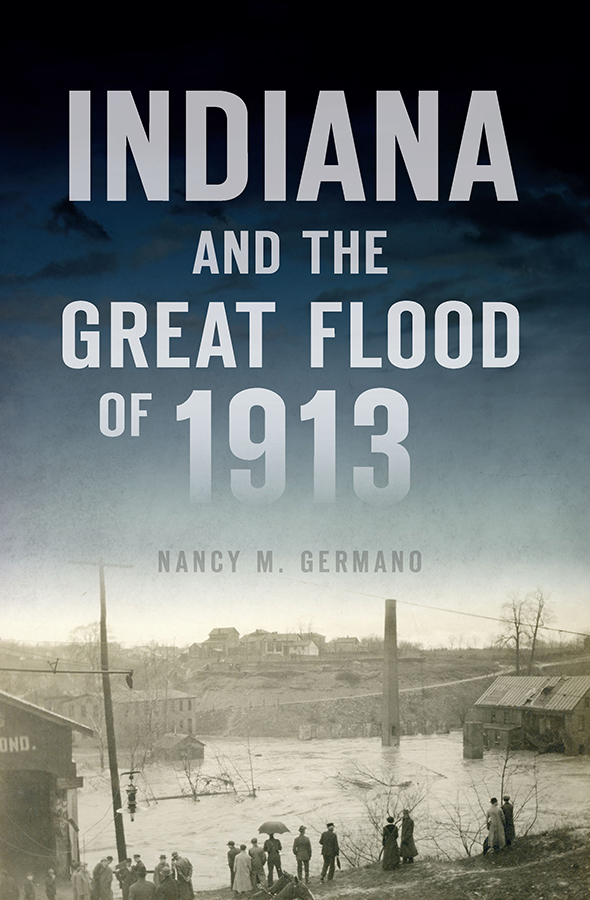

INTRODUCTION

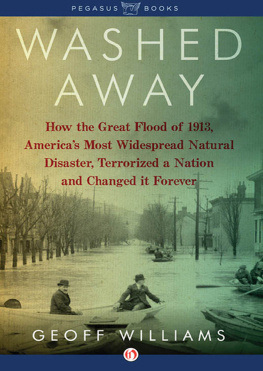

In March 1913, severe weather moved across the Midwest in the United States, making national headlines. Indiana residents had experienced many floods, but the Great Flood of 1913 set new records for water levels, lives lost and damage caused. According to a U.S. Congressional report, the flood stood out from its predecessors because of the exceptional magnitude and intensity of its storms and because the greatest damage it caused occurred along tributaries, which had not been the case in the past. The U.S. Weather Bureau reported a rain total in Indianapolis in excess of six inches during the period beginning March 23 and March 27, 1913. While six inches of rain over a five-day period is not an extraordinary amount, the Weather Bureaus reports indicate that this storm followed a month of unsettled weather patterns that alternated between freezes and thaws and a high amount of precipitation. Furthermore, an unusually high amount of precipitation had occurred in January 1913. The ground was saturated when the March storm arrived. According to the Weather Bureaus local office, the flooding that resulted cost the lives of scores of people, rendered many thousands homeless, and destroyed property beyond estimate. The bureau director explained, The enormous losses over such an extended area is unprecedented in the history of this portion of the United States, and it must follow that an occurrence so unusual must have been produced by extraordinary weather conditions. Although extreme weather clearly contributed to this disaster, many other factors exacerbated the effects of the weather event. Indiana history illuminates the story of the 1913 flood, which became known as the Great Flood, and it was the event against which future floods were compared.

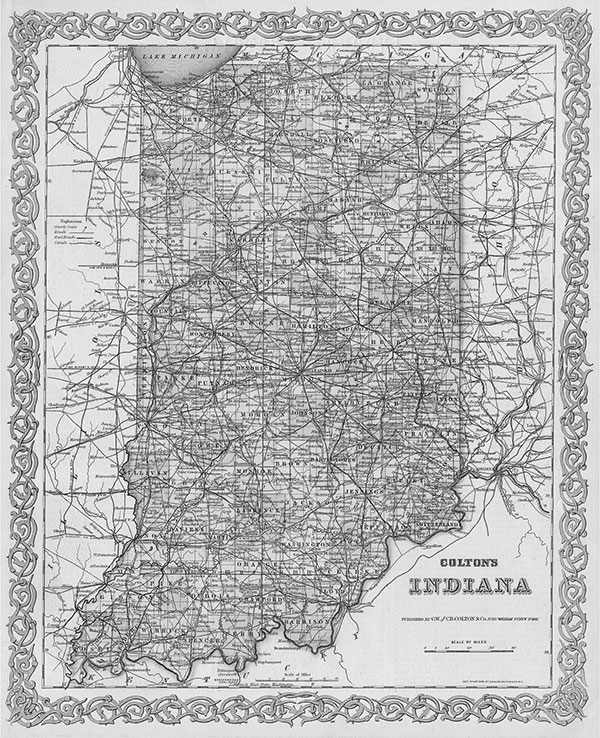

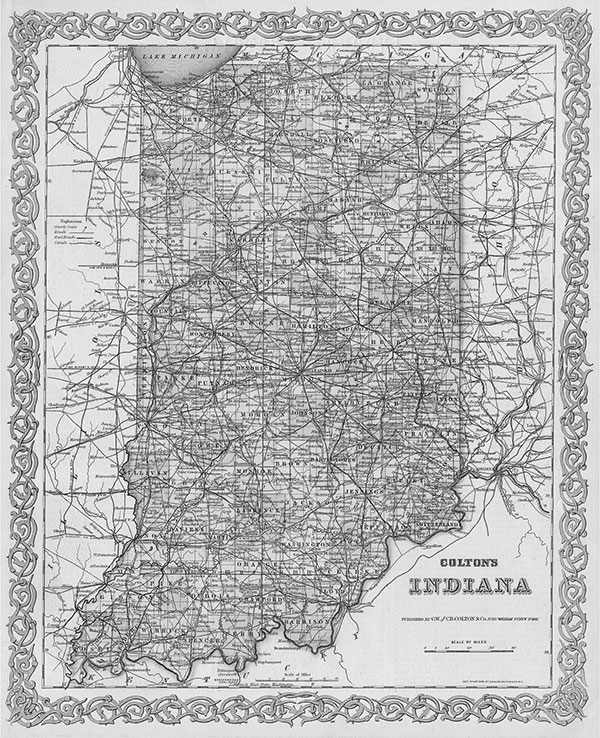

Coltons Map of Indiana, circa 1886. Indiana Historical Society.

The disaster revealed an interdependentyet conflictedrelationship between the people and the landscape of Indiana. By the early twentieth century, Indianapolis and urban centers across the state boasted their growing factories, employed residents and plentiful homes. Yet the concentration of homes and businesses in floodplains, along with the accumulation of human waste and industrial pollution in rivers, made the effects of the flood much worse. By 1913, development had progressed to the point where residents were faced with a philosophical dilemma concerning the value and wisdom of continuing to encroach on and manipulate the flood-prone landscape. The apparent effects of past actions raised questions about how to proceed.

Although the 1913 flood caught the attention of Hoosiers, the immediate concern was recovery. Governor Samuel M. Ralston and President Woodrow Wilson rushed to the assistance of communities, while mayors organized efforts to provide aid to flood sufferers. Business owners tried to salvage what they could to help others. Church groups, charitable organizations and neighbors pitched in to help families clean up, disinfect, repair their homes and restart their lives. Citizens, city administrators and policy makers soon turned to debates about what could be done to prevent a future flood like this one.

Today, towns display plaques and lines on the sides of buildings to mark the height of the 1913 floodwaters. Archives hold photographs and newspaper clippings about the disaster. The Great Flood lives in the memories of Hoosiers in these ways, but in other ways, it has been erased. Many towns have significantly changed in the last one hundred years, and the flood changed the trajectory of some when businesses did not survive or when they decided to move to another location. When we view black-and-white photographs of the Great Flood, it may seem like the distant past, but its story remains relevant today.