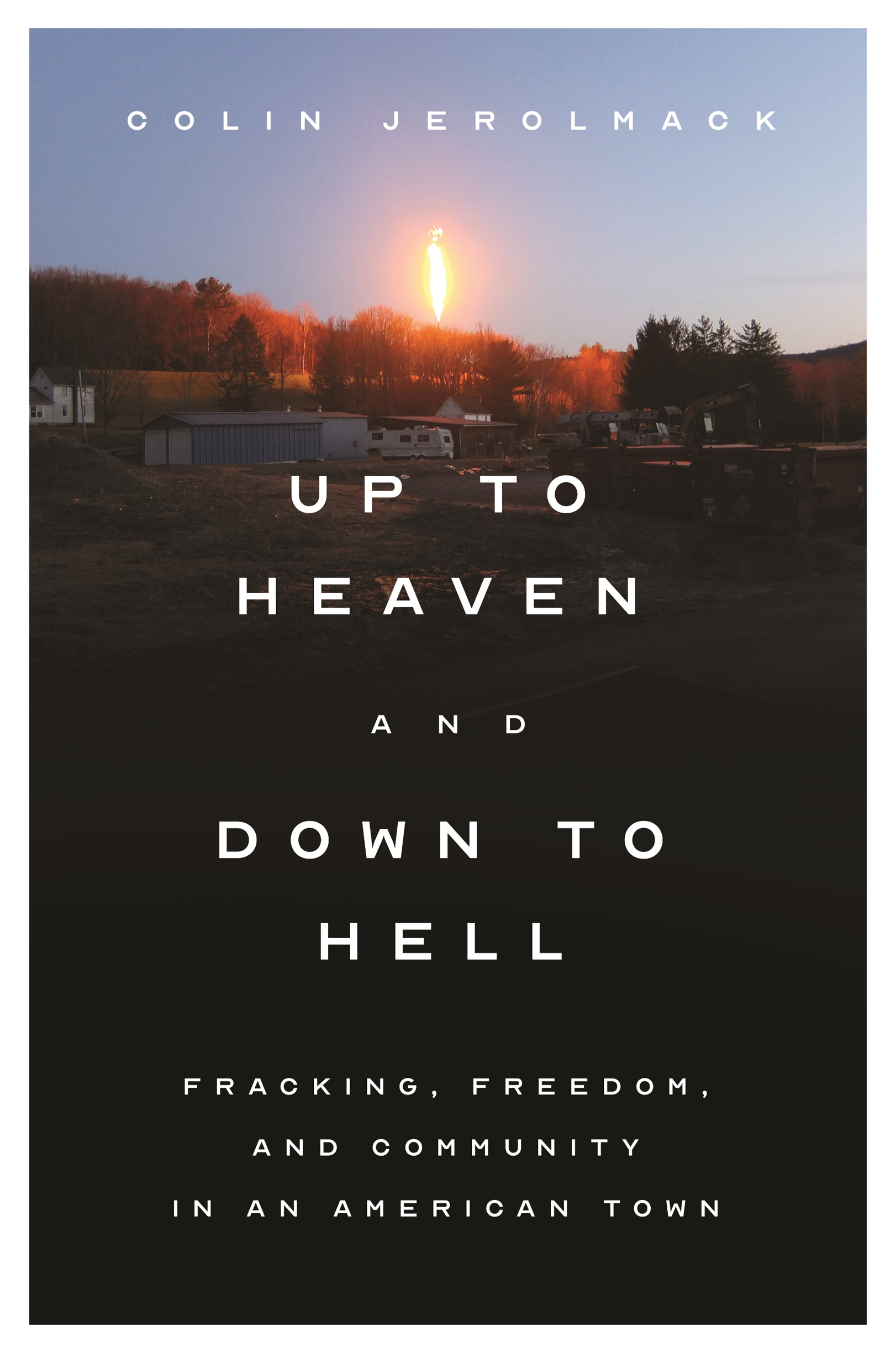

UP TO HEAVEN AND DOWN TO HELL

UP TO HEAVEN AND DOWN TO HELL

Fracking, Freedom, and Community in an American Town

COLIN JEROLMACK

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Colin Jerolmack

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jerolmack, Colin, author.

Title: Up to heaven and down to hell : fracking, freedom, and community in an American town / Colin Jerolmack.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020045112 (print) | LCCN 2020045113 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691179032 (hardback ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9780691220260 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Gas industryEnvironmental aspectsPennsylvaniaWilliamsport. | Hydraulic fracturingEnvironmental aspectsPennsylvaniaWilliamsport. | Oil and gas leasesPennsylvaniaWilliamsport. | LandownersPennsylvaniaWilliamsport. | EnvironmentalismPennsylvaniaWilliamsport. | Williamsport (Pa.)Environmental conditions.

Classification: LCC HD9581.U52 P445 2021 (print) | LCC HD9581.U52 (ebook) | DDC 338.2/7280974851--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020045112

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020045113

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Meagan Levinson and Jacqueline Delaney

Production Editorial: Ellen Foos

Text Design: Karl Spurzem

Jacket Design: Faceout Studio

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Maria Whelan and Kathryn Stevens

Copyeditor: Stephen Twilley

Jacket images (front and back) courtesy of Colin Jerolmack

To Shatima. For waiting. And for everything else, too.

Your rights extend under and above your claim

Without bound; you own land in Heaven and Hell

WILLIAM EMPSON, LEGAL FICTION (1928)

ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

Land of the Freehold

If I ever had to leave this property, Id suck on a gun barrel.

When Georges parents bought the farmstead, in 1947, the house was rudimentary; a tornado destroyed the barn the next year. As the years went by, Georges father patiently fixed the place up and rebuilt the barn. He finally got around to starting work on an indoor bathroom to replace the outhouse in the fall of 1957. But a few days before Christmas, just as the biting winter winds began to sweep across the Appalachian foothills, he fell off a ladder while hanging plastic over the kitchen windows. Hit his head on a rock. Georges glassy eyes meandered from a strip of peeling linoleum to the very window where his mother, cooking dinner at the time, watched his father die. Mom had to put his body and the seven kids in the car and run him to the hospital. George was just two years old. A bachelor to this day, he stayed home after all his siblings moved out, to help his mother raise a baby girl that his sister had planned to put up for adoption (a child whom he came to consider his), and then to care for his mother until her death, in 2008.

To be the steward of his dads land, George beamed, was all I ever wanted. He devoted most days to his estate. He paced the perimeter for hours each day (I just love to walk my property), religiously mowed the grass (which took the better part of a day), and tended to the lilac bushes his mother planted long ago. And he took hundreds of mundane photographs of his land with disposable film cameras, which he planned to compile as a book that will stay with the property after Im dead and gone [as] a record of what went on here. George loved showing off his land and hated to leave the premises for even a few hours. He seldom did. In fact, he claimed it had been thirty years since he overnighted somewhere else. My daughter had to see Disneyland, he chuckled.

I first met George in the spring of 2013. The Texas-based Anadarko Petroleum Corporation was in the midst of drilling six natural-gas wells on four acres of leased land it had cleared in a field 350 yards behind his house. It had long been rumored in these parts that vast reserves of methane lay frozen inside a stratum of shale buried a mile or so underground. Over the last century, ragtag wildcatters and a few more-established petroleum companies had periodically poked thousand-foot holes in the earth in the hopes of tapping into pockets of the gas that leaked out of the porous rock. In time, they threw everything but the kitchen sink down vertical wellbores to try to shatter the shale and increase the flow rate of escaped methane molecules. Some tried dynamite, and even napalm; the government once experimented with nuclear bombs. It was mostly a fools errand. Even when wildcatters began hydraulically fracturingaka frackingshale in the 1950s, by forcing water, lubricants, and sand down the well at pressure high enough to open up tiny fissures in the rock, the value of the amount of gas recouped from each well seldom exceeded the cost of drilling. Drilling vertically into shale is like taking a core sampleeach well can only tap a tiny cross section of it.

In the 1980s and 1990s, petroleum companies began experimenting with remote-controlled drill bits that, during their approach to the rock layer, could gradually angle ninety degrees so that they tunneled along the methane-laced seam of shalethe equivalent of tapping the vein. It was only by marrying fracking with so-called horizontal drilling that the largest deposit of natural gas in the United States, the Marcellus shale play (industry parlance for a large shale mineral deposit), was finally opened up for development this century.

It is a cornerstone of American property law that estate ownership traditionally extends above and below the lands surface, excepting instances in which surface rights and mineral rights have been explicitly severed by a previous title holder. The idea descends from the medieval Roman jurist Accursiuss dictum Cuius est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et ad inferos (Whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to heaven and down to hell). This meant that energy companies could only extract the gas beneath Georges and his neighbors property if landowners gave them permission. It also meant that energy companies had to pay them a leasing bonus, compensate them for any surface disturbance to the land, and share a portion of the royalties generated by selling the gas extracted from their estate. George was one of thousands across the poverty-stricken rust belt who eagerly leased their mineral rights in the ensuing land rush, inviting an energy company to drill under his beloved homestead in the hopes of winning the fracking lottery.

Wearing a threadbare Montoursville High School Basketball T-shirt, George excitedly led the way to the parking lotsized gravel well pad. Im fascinated by what theyre doing and how theyre doing it and how much it takes to do it. Its really, really neat to watch it. I come down here every day. The trail of trammeled grass from his back door to the pad was testament to the retirees preoccupation. As we scrambled atop the berm overlooking the giant industrial operation, a 150-foot-tall drilling rig loomed like a larger-than-life erector set, methodically driving three forty-foot segments of threaded steel drill pipes into a predrilled hole. George marveled at the engineering feat we were witnessing: ultimately, the threaded-together sections of steel pipe would plunge vertically for a mile, then gradually arc horizontally as they neared the shale layer, where they would then burrow parallel to the surface for another mile through the rock seam under Georges and his neighbors properties. After cement casing was poured as a protective lining, pipe-bomb-like depth charges placed along the horizontal portion of the wellbore would be detonated, unleashing a hail of ball bearings to perforate the shale. Finally, dozens of big rigs carting millions of gallons of water, sand, and chemical-laced lubricants would idle on the well pad as their contents were mixed and then injected at high pressure into the well to frack it, creating thousands of tiny fissures in the rock that allow the gas to escape. (The sand acts as a proppant, holding the fractures open.)