Fergus Bordewich - Washington

Here you can read online Fergus Bordewich - Washington full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

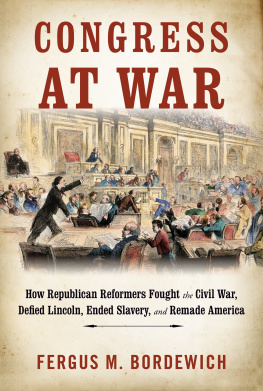

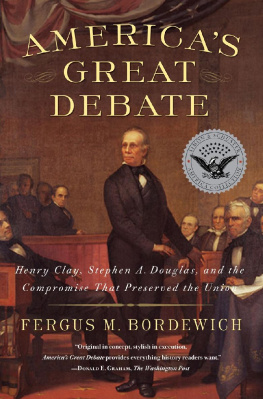

- Book:Washington

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Washington: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Washington" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Washington — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Washington" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Making of the American Capital

For Richard H. Parvin and Marjorie Allen Parvin

A great city would really and absolutely be raised up, as if by magic.

A Citizen of the World, in The Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, 1789

This place is the mere whim of the President of the United States. During his life, it may out of compliment to him be carried on in a slow manner, but I am apprehensive as soon as he is defunct, the city, which is to be the boasted monument of his greatness, will also be the same.

An immigrant stonemason, 1795

I N THE COURSE OF writing Washington: The Making of the American Capital, I benefited from the accumulated wisdom of many people who opened unsuspected windows onto the political battles and sometimes elusive personalities of the early republic. I am especially grateful to the members of the First Federal Congress Project, who generously shared both their scholarly resources and their enthusiasm for the politics of the 1790s. Above all, I am indebted to Kenneth R. Bowling, coeditor of the project, for his wise suggestions and provocative insights, which improved this book in more ways than I can count.

Bob Arnebecks exhaustive chronicle of the capitals early years, Through a Fiery Trial, lit my path into the dense thickets of politics on the Potomac. He responded to my many queries with unfailing good humor, and counseled skepticism toward conventional thinking about the capitals birth. Felicia A. Bell of the U.S. Capitol Historical Society pointed me toward invaluable documents illuminating the role that slaves played in the capitals construction.

C. M. Harris, the editor of William Thorntons papers, greatly enriched my understanding of the designer of the Capitol. William C. Allen, historian of the United States Capitol, revealed to me the ghostly vestiges of Thorntons building beneath the fabric of the modern Capitol. Mrs. Ermin Penn was an eloquent guide to the poignant locales of Thorntons life on the lovely Caribbean island of Tortola, his original home.

Elizabeth M. Nuxoll, currently the editor of the John Jay Papers, piloted me through the papers of Robert Morris, her former bailiwick, and helped me to understand the character of the larger-than-life financier who played such a great role in the capitals birth. Christopher Densmore, director of the Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College, fielded questions regarding Quakers and the antislavery movement with his usual precision and graciousness. Anna Coxe Toogood of the National Park Service brought alive Philadelphia during its years as the nations capital. David A. Smith of the New York Public Library helped me to ferret out invaluable editions of early newspapers.

Anna M. Lynch and Leslie Morales were of exceptionally valuable assistance during my research in Alexandria, Virginia. Patsy M. Fletcher, of the City of Washingtons Office of Planning, unearthed many useful sources of local information in the District of Columbia. Chris Cole of Stone Ridge, New York, took time from a busy workday to explain to me with a craftsmans delight the use of the historic tools that were employed by laborers in the 1790s.

Without the unflagging commitment of my editor, Dawn Davis, and my agent, Elyse Cheney, this book would never have come to fruition. They have, as ever, my gratitude.

Nor could I have succeeded without the support of my wife, Jean, and my daughter, Chloe, whose love and patience I can only hope to repay with this book.

A S THE LAST DECADE of the eighteenth century dawned, the United States was the third world of its time, less a nation than a weak and disorderly congeries of semi-independent states, more like the rickety Yugoslavia of the 1990s than to the superpower of today. Settlement extended only from the Atlantic seacoast to the wilderness of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Ohio. Philadelphia, its largest city, had a population of just forty-five thousand; and New York, only about thirty thousand. With native industry in its infancy, Americans still imported from Europe such necessities as shoe buckles, spurs and stirrups, pistols, razor strops, paint, fishing hooks, buttons, toothbrushes, and paper. It took three days to travel the one hundred miles from Philadelphia to George Town, Maryland, on corrugated roads so afflicted with stones, stumps, and ruts that it was customary for drivers to call to their passengers to act as ballast by first leaning to one side and then to the other, to keep the coach from overturning. A crazy quilt of state jurisdictions maddeningly compounded the difficulty of travel. When Thomas Jefferson journeyed from Richmond to New York in March 1790 to take up his duties as secretary of state, he had to juggle three different state currenciesthose of Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvaniain order to pay his expenses along the way.

For a decade, the frail government of the United States had teetered on the brink of financial default and depended on foreign lenders for its financial survival. Annual interest on national and state debts was $4.5 million, at a time when the federal operating budget was about $600,000 per year. Worthless paper money had made a wreck of business obligations. States ignored congressional requisitions. Unemployed workmen wandered the streets of the cities. Farmers complained of crushing taxation. Even a friendly observer, the French traveler J.-P. Brissot de Warville, lamented that the states were just falling to ruin. They had no government left, the constitution was detestable; there was no confidence to be placed in the Americans, the public debt would never be paid; and there was no faith, no justice among them.

No one really knew if the system that was established at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 would actually function. How would the checks and balances work? Who would control foreign policy? Who had the authority to interpret the Constitution? How was the president to be addressed? (Some seriously suggested His Exalted High Mightiness; others contemptuously dismissed the proposed title president as appropriate to a fire company or a cricket club.) Would the Northern states help defend the Southern against a slave uprising? Would the South come to the aid of the North in the event of a foreign invasion? None of the answers was obvious. Local officials were incompetent, or worse. Congress seemed little better. Full democracy repelled virtually all the men who were charged with making it work. The people should have as little to do as may be about the government, Connecticut Senator Roger Sherman warned. They lack information and are constantly liable to be misled. James Jackson, a congressman from Georgia, was alleged to have once waved his pistols at visitors in the public gallery and threatened to shoot them if they made too much noise. Jackson at least took his job seriously. During debates, many of his colleagues could typically be seen reading newspapers and exchanging bawdy limericks with one another. Of eighty-six senators who served during the 1790s, one-third would depart in boredom or disgust before their terms expired.

Only a small percentage of the countrys four million inhabitants had any role in political life. Just under seven hundred thousand were slaves, who had no rights to liberty or property at all. And it would be a generation before any woman was heard to express her opinions in a political forum. About half of all free white men were disenfranchised by property qualifications, and many others lived too far from polling places to actually vote. In the elections to select delegates to the state conventions that debated ratification of the Constitution, only about one hundred sixty thousand people had voted, just one twenty-fifth of the population. Rules for participation in government varied widely from state to state. In Pennsylvania, all taxpayers were eligible to hold office; in Virginia, the requirement was ownership of at least twenty-five acres of improved land; and in South Carolina, candidates had to prove that they were worth a minimum of $8,500 to stand for a seat. In some states, presidential electors were selected by popular vote, in others by the state legislature, and in at least one, New Jersey, by the governor and his cabinet.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Washington»

Look at similar books to Washington. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Washington and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.