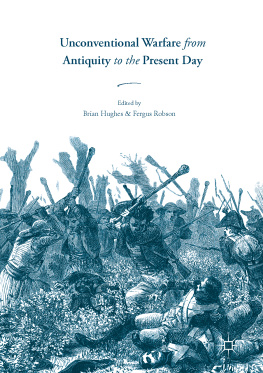

This volume has its origins in a one-day international conference hosted by the Centre for War Studies at Trinity College, Dublin, generously funded by the Trinity Long Room Hub Research Incentive Scheme, and held in Trinity in March 2015. Entitled Unconventional Warfare: Guerrillas and Counterinsurgency from Iraq to Antiquity, the workshop brought together scholars interested in the phenomenon of fast-moving, irregular forces employing hit-and-run tactics against more orthodox armies in a variety of theatres and across the centuries. Contributors traced the lived experiences and historical representations of this mode of war from antiquity and the early modern period through the turning point of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic era and on to the guerrillas role in, and state and military responses to, the twentieth-century wars of decolonization. One strong thread running throughout the workshop was an interest in narratives, in how this form of conflict was presented by its practitioners, its victims, and in collective memory; how it was perceived, and how this in turn often served as a motor for violence and counter-violence. As a group, we were interested in challenging and problematizing the frequently recurring dichotomy between regular and irregular fighters based, as it is, on an often idealized or even flawed understanding of the role and behaviour of traditional armed formations. Participants also explored how guerrillas relate to the communities from which they emerge and the similarly entangled roles of guerrilla and bandit, brigand, freedom fighter, fanatic, or terrorist.

The present volume is an extension and expansion of the scholarly discussion that emerged from this workshop, consisting of chapters by participants and others specially commissioned for the volume. It has brought together recently graduated doctoral candidates, early career scholars, and established academics from universities in Britain, Ireland, Europe, and the United States. The volume employs a regressive format, beginning with the twenty-first-century conflict in Afghanistan and working backwards, chronologically, to the seventh century bc . This novel approach allows us to avoid teleological assumptions about the modernity or singularity of terrorism and guerrilla conflicts, to look forwards as well as backwards, and to identify continuities alongside rupture and change. Chapters are divided into two sections. The essays in Part I will cover the modern era from ongoing conflict post-2000 to the nineteenth century and the American Civil War. Part II opens at what might be seen as the temporal fulcrum, the Revolutionary-Napoleonic era, with insurgency in early modern Europe, and continues back to our end point in Greece in the seventh century bc . The 11 chapters produced here bring together the most recent research and writing from scholars in History, Politics and International Relations, Archaeology, and Classics, all of whom share an interest in the dynamics of small war.

Historiography

The entrance of US forces into Afghanistan in 2001, the joint USBritish invasion of Iraq from 2003, and the subsequent military and political difficulties that developed, have coincided with indeed encouraged a vigorous renewed interest in counterinsurgency operations after what might be viewed as several decades of relative neglect. In 2006, the US army published Field Manual 324 ( FM 324 ) as a doctrine for modern counterinsurgency (or COIN).

At the heart of this debate is a disagreement about the use of history in understanding unconventional war and strategizing in the present, and accusations that the past has been misunderstood or, worse, misrepresented by those drawing parallels and lessons for application in present conflicts. The extent to which lessons from the past can be applied to modern conflicts remains contested as scholars continue to examine the transferability of knowledge between campaigns.

The comparative element in much of this literature, and other work on insurgency and counterinsurgency, has remained, for the most part, temporally narrow and rooted heavily in the modern era. For those interested in modern British counterinsurgency, and also those encouraged to look backwards by its failures in the twenty-first century, there is a significant focusing of attention on the wars of decolonization after 1945, what has been described as the classic age of British counterinsurgency. But the history of this form of war goes back much further.

Military doctrine in eighteenth-century Europe did also, in fact, clearly identify small war, kleiner krieg , or la petite guerre in opposition to war as practised by field armies on campaign and fighting in set-piece battles and sieges. This understanding, however, referred not so much to insurgency but to the deployment of regulars in raiding, ambush, and reconnaissance: irregular operations. It was only during and after the wars of the French Revolution, in particular the Peninsular War, that the more modern notion of the guerrilla began to take shape. This was a direct consequence of the spectre, and myth, of the Spanish guerrilla as a national uprising, as well as a variety of contemporary conflicts and concomitant changes in the ways armies were understood, raised, deployed, and imagined. Carl von Clausewitz identified the phenomenon and he and others attempted to theorize it in light of the French leve en masse , the Spanish guerrilla, and the Russian and German national uprisings against the French. These resonances across centuries would seem to require the type of inquiry being undertaken in this volume, and an even longer temporal gaze.

As the contributions in this collection make clear, there is much to be gained by identifying continuities and change over the longue dure . Alexander Hodgkins points to the coherent mobilization and deployment strategies used by insurgents in East Anglia and Devon (Chapter A Great Company of Country Clowns: Guerrilla Warfare in the East Anglian and Western Rebellions (1549)) which are similarly evident in Raphalle Branches description of FLN policies in Algeria (Chapter The Best Fellagha Hunter is the French of North African Descent: Harkis in French Algeria) and Daniel Sutherlands evocation of the traditions and structures of guerrilla recruitment and action in Civil War United States (Chapter American Civil War Guerrillas). On the counterinsurgent side, the strong parallels between the ways in which (some) French commanders practised pacification in Fergus Robsons chapter (Chapter Insurgent Identities, Destructive Discourses, and Militarized Massacre: French Armies on the Warpath Against Insurgents in the Vende, Italy, and Egypt) and the soft COIN analysed by Julia Welland in Afghanistan (Chapter Gender and Population-centric Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan) emerge as striking evidence for a cyclical process of learning (and forgetting) effective repressive strategies. While the messiness and complexity of insurgencies and unconventional warfare are evident throughout this volume, Matthew Lloyd (Chapter Unorthodox Warfare? Variety and Change in Archaic Greek Warfare ( ca . 700 ca . 480 BCE)), Brian McGing (Chapter Guerrilla Warfare and Revolt in 2nd Century BC Egypt), Alastair Macdonald (Chapter Good King Roberts Testament?: Guerrilla Warfare in Later Medieval Scotland), and Sen Gannon (Chapter Black-and-Tan tendencies: policing insurgency in the Palestine Mandate, 192248), in particular, demonstrate the analytic flaws of binary models of Western-non-Western, conventional-unconventional, Scottish-English, and colonial counterinsurgency ways of war.