The Last of Africas Cold War Conflicts

The Last of Africas Cold War Conflicts

Portuguese Guinea and its Guerrilla Insurgency

Al J Venter

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Al J Venter 2020

ISBN 978 1 52677 298 5

eISBN 978 1 52677 299 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52677 300 5

The right of Al J Venter to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail: Uspen-and-sword@casematepublishers.com

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Prologue

A pproaching Bissau from the air was always a different kind of experience. I did the trip often, for General Antnio de Spnola was easy on the use of military aircraft by the handful of visiting foreign journalists that could inveigle a visa to cover his war.

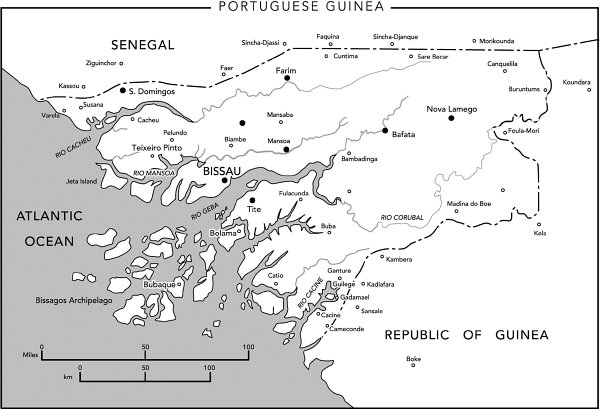

Flying in from the Cape Verde Islands, the coast loomed up ahead, stark against a hazy African horizon. A dozen tiny ribbons of rivers snaked through the low-lying swampland approaches, the pattern crazily uneven and broken sporadically by the squares and triangles of hundreds of rice paddies spread out between the mangroves. From where we flew, they looked like angular, heavily lined corduroy sheets. Even thirty kilometres out the sea was a dirty, muddy brown, like the kind of turbulence you see at anchorages outside some industrial harbours, but then Bissau has no industry to speak of. Its the same when approaching the estuaries of the Congo and Niger rivers farther down the West African coast.

Only occasionally was the rhythm broken by the dark-stained sail of a nhominca , the Portuguese-type fishing boat which is in everyday use along this seaboard as far north as Mauritania. Centuries ago local fishermen in Senegal, Gambia, Guinea and Sierra Leone adopted the protruding keel design, which tourists today are more likely to associate with Estoril.

Then, quite suddenly, the city lay before us and, viewed from the air, Bissau was a bit larger than expected and semicircular in shape. The resemblance to Banjul, the Gambian capital city about a hundred miles to the north was striking, both places lying on a promontory that faced the ocean. This was probably one of the reasons why a Soviet-built Antonov transport plane, bearing the colours of the Guinea Air Force landed at Bissau in 1971. The stocky aircraft had lost its way on a flight between Labe and Conakry in the Republic of Guinea and mistook Bissalanca for Bathurst.

The crew was still being held in Bissau when I was there, though. President Skou Tour, the Marxist president of the Republic of Guinea, rejected the offer.

Coming in to land in Portuguese Guinea one couldnt help but notice that all roads leading outward from Bissaus cathedral doubled back again on reaching the outskirts of town, almost as if they airport, a short drive on the road north out of the capital, was an impressive affair set across an otherwise uninteresting, flat countryside.

Alongside the heavy tarmac fortifications stood rows of squat artillery pieces behind raised gunpits, their muzzles covered in canvas, their role, clearly, to protect about thirty military aircraft, all in various stages of readiness for morning operations. Wed arrived early after an eighteenhour flight from Lisbon and it had been a long haul.

About a dozen Alouette helicopters and the same number of Fiat G-91 jets were concentrated at the far end of the runway, well away from what one officer referred to as the prying eyes of civilians who pass through en route to Europe and beyond. Still more planes, Harvards and Dorniers, were parked close to the terminal building, their engine cowlings bright dayglo orange paint that reflected in the early morning sun; the gaudiness, I was told, had something to do with identification and spotting in the event of one of the planes being forced down.

On its own pad nearby stood one of Bissaus two Nord Noratlas transports, the same air freighters Id used often enough to gad about in Angola. These NATO-type planes looked impressive in their wavy green and brown camouflage paint and were tasked for daily supply runs into the interior.

An unusual aircraft, a modern jet fighter, stood on its own in a bunker near the fringe of the airport cluster, its long, low-slung silhouette contrasting with the stocky fighters around it. Incredibly, it was one of Britains Second World War Glostor Meteor fighters. On its fuselage, as if someone tried to add a rider to a riddle, was painted, in large black capitals: ENTERPRISE FILMS. Photographs of both this plane and the Antonov were forbidden for security reasons whatever they were. It was perhaps inevitable that Id snap them eventually as virtually all my movements into the interior were through Bissalanca airport.

The story regarding the Meteor goes like this: during the Biafran War the rebel leader Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu bought two jet fighters from an international arms salesman, to replace French Vantour bombers that hed intended to use against Federal lines and which were destroyed on the ground outside Uli airport by Nigerian Air Force MiGs before they were ever put into effective use.

Meantime, both Meteors were flown out of Britain illegally, it transpired and once in international air space, the planes headed down the West African coast for Nigeria.

The designers of the Meteor series, a remarkable plane and well ahead of its time they first flew in 1943 had never intended them to be used in long-range operations, so it was not altogether surprising that halfway to Africa, one developed engine trouble and had to be ditched into the sea. The other landed at Bissau and like the Antonov, remained neglected, dilapidated and for the rest of the war, little more than an embarrassment to a Portuguese government that only wished to forget that Biafra ever existed.

Tackled on the subject of the jets during my visit, General Spnola refused to be drawn. As far as he was concerned, the planes had made emergency landings and that was that. Their origins did not concern him, he told me, nor where they might have been headed. The Meteor pilot, a Brit, had been repatriated shortly after hed landed and nobody had ever stepped forward to claim the jet.

What did emerge years later was that Enterprise Films was the cover organization in Britain which handled the sale, ostensibly for use in a longforgotten film on the Battle for Europe. Legal action had since been taken by the British government against individuals responsible for the sale, all eventually convicted on the grounds that they had not declared the true purpose of the venture. Newspapers concluded at the time that the charge levelled was one of arms smuggling and the offence a military one.

Next page